Case Presentation: 68-year-old male with a history of recurrent angioedema, complicated by intubation, presented to the emergency room (ER) for progressive tongue swelling and dyspnea prior to arrival. He was on aspirin 81 mg for years with a recent addition of cilostazol for peripheral artery disease. Physical exam was significant for tongue and lip swelling. He did not have urticaria, abdominal or extremity swelling. He received several intravenous medications including epinephrine, methylprednisolone 125 mg, diphenhydramine 25 mg and famotidine 20 mg in the ER. Initial lab work was only significant for acute kidney injury with a creatinine of 1.71 mg/dL. Despite these initial treatments, the patient did not improve and was subsequently intubated for airway protection and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Following one day in the ICU with minimal improvement, the patient received human C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) while further lab work was pending. The patient received a second dose of human C1-INH prior to a successful extubation on day 4 of hospitalization. Following extubation, extensive history was taken from the patient in an attempt to elucidate cause of his angioedema. The patient was eventually discharged on a prednisone taper, daily loratadine and famotidine. He was instructed to discontinue aspirin and recommended to stop cilostazol given it was a recent addition to his medications.Work up showed an elevated IgE of 142 IU/mL. C1-INH antigen was negative. C1-INH level and function, were normal. C1Q complement level and function, C4, and total complement were also normal. Tryptase was normal when drawn in the ICU, unfortunately, no tryptase was initially drawn in the ER.

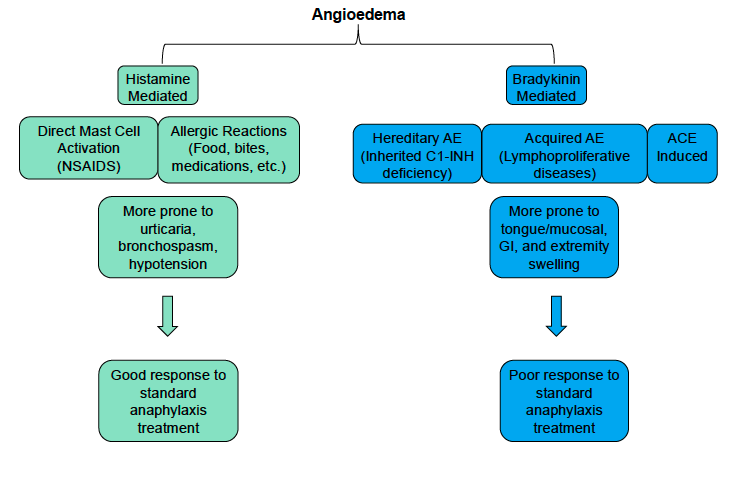

Discussion: Angioedema is localized swelling of subcutaneous or submucosal tissue, caused by vasoactive mediators that increase vascular permeability. Angioedema can further be classified by the presence or absence of urticaria. In this case, the patient was diagnosed as idiopathic angioedema that was not responsive to antihistamines. The pathogenesis is not fully understood and there are no specific laboratory tests to confirm this diagnosis. Typically, these patients do not have a family history to suggest a hereditary angioedema, no urticaria, and normal C1-INH levels and function and complement levels. These patients are more prone to tongue and mucosal swelling when compared to C1-INH deficiency and unfortunately, patients in this category typically do not improve with traditional antihistamine and corticosteroid treatment. We ultimately recommended he discontinue aspirin, although his angioedema likely cannot be attributed to this as aspirin-induced angioedema typically improves with corticosteroids and antihistamines.

Conclusions: In summary, not only is our understanding of the disease pathogenesis lacking, there is suboptimal understanding in treatment. Studies have found promising use of tranexamic acid, C1-INH, fresh frozen plasma, and etcetera, however, in an acute setting, it is common to broadly treat these patients with corticosteroids and antihistamines, despite knowing that they ultimately will not improve angioedema or prevent further episodes. This case highlights the difficulty in establishing an appropriate diagnosis for non-histaminergic angioedema and shows a typical “throw the kitchen sink at it” approach to treating tongue and laryngeal angioedema.