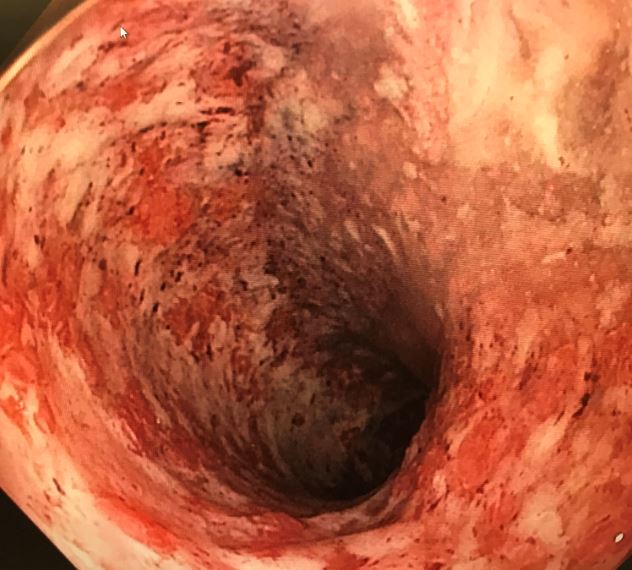

Case Presentation: The patient was a 38 year old male with a 5 year history of ulcerative colitis (UC) who presented with a flare of symptoms during the past year, resulting in a 60 lb weight loss. He had been having up to 42 bloody bowel movements per day. The patient was found to have fulminant ulcerative pancolitis with pseudomembranes that was refractory to treatment with high dose prednisone, infliximab, and 6-mercaptopurine. Clostridium difficile PCR testing was negative. He was admitted for intravenous methylprednisolone, total parenteral nutrition, and cyclosporine salvage therapy with plans for surgery if he did not respond to therapy. VTE prophylaxis was provided with sequential compression devices due to the patient’s hematochezia. His hemoglobin had remained stable during admission, and he did not require any packed red blood cell transfusions. Three days later, the patient reported chest pain and shortness of breath. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed pulmonary emboli (PE) involving segmental arterial branches to the right and left upper lobes as well as right lower lobe. The patient was started on a heparin drip during hospitalization. Interestingly, he reported a decrease in the number of bowel movements after starting anticoagulation. He was discharged on warfarin and prednisone with plans to start tofacitinib as an outpatient. The patient ultimately failed treatment and required a total proctocolectomy. Due to the PE, the patient’s surgery was delayed several months from initial hospitalization. When he eventually had surgery, he developed a large pelvic hematoma requiring further surgical intervention.

Discussion: Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract that includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. IBD patients are at 2-3 times increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Much of this risk is due to systemic inflammation activating the coagulation cascade, resulting in platelet aggregation and a hypercoagulable state. Hospitalized IBD patients may be immobile and at an even greater risk of VTE. Current guidelines support that hospitalized IBD patients with nonsevere GI bleeding should receive pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. However, IBD patients with severe GI bleeding rendering them hemodynamically unstable should receive mechanical thromboprophylaxis with intermittent pneumatic compression.This case highlights the importance of VTE prophylaxis in IBD patients. These patients are at an increased risk for thromboembolic events with potential for significant morbidity and mortality. Physicians may be hesitant to initiate pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in patients admitted with hematochezia due to excessive bleeding risk. This runs contrary to studies that have shown no increase in the incidence of major bleeding in IBD patients who received treatment. Patients with life threatening bleeding should certainly have anticoagulation held.Of note, there is evidence that low molecular weight heparin may be an effective treatment of active UC. More research is needed to evaluate whether unfractionated heparin may offer a similar benefit.

Conclusions: IBD patients admitted for a flare should receive pharmacological VTE prophylaxis due to the increased risk of thromboembolic events unless they have life-threatening bleeding. More awareness is needed among hospitalists to properly provide VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized IBD patients.