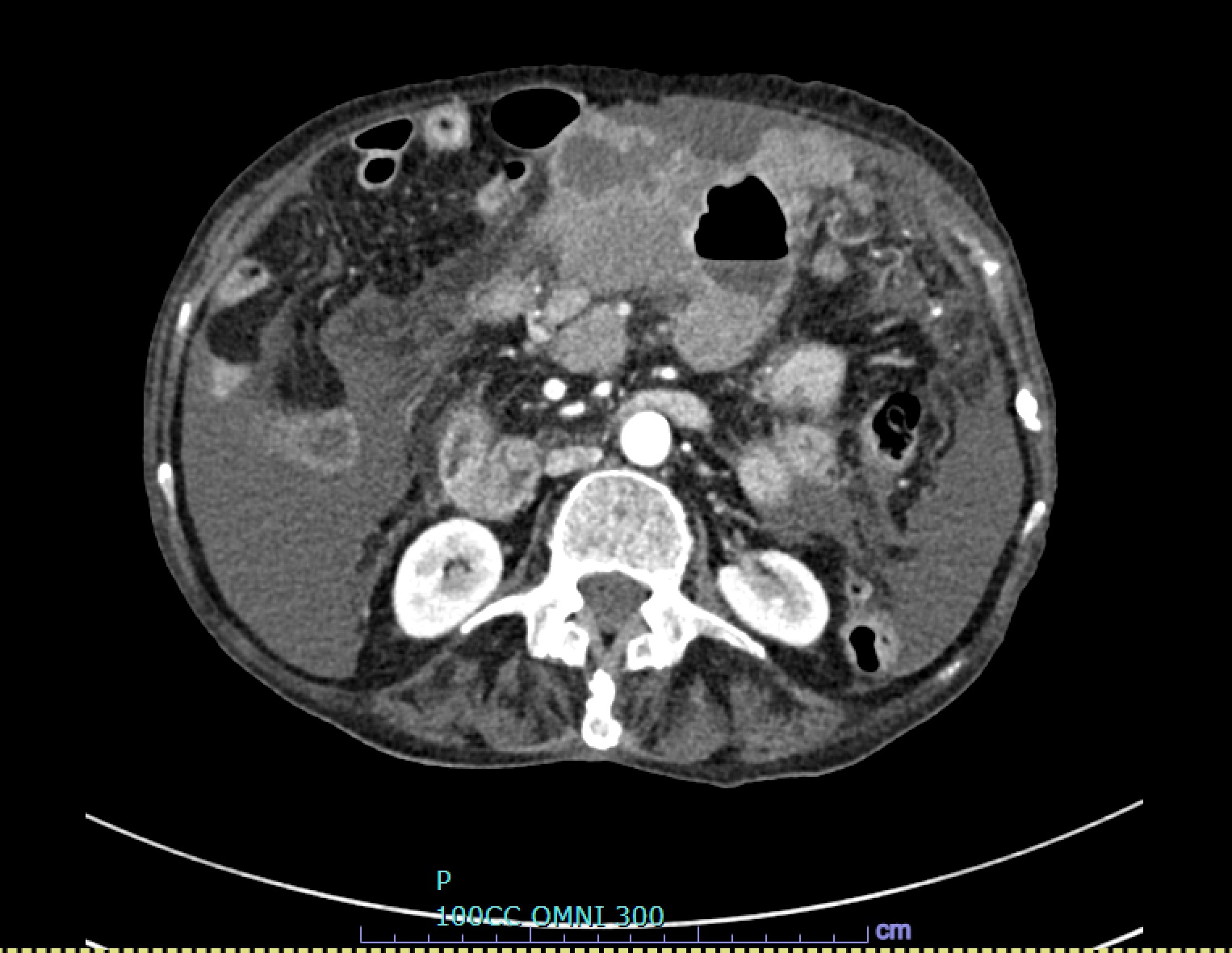

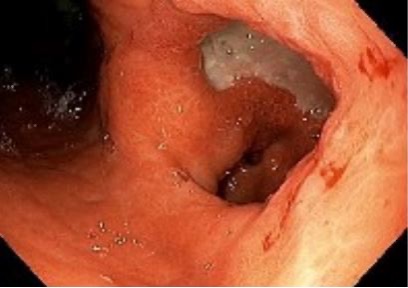

Case Presentation: An 82-year-old woman with a history of cirrhosis (unknown underlying etiology) and intermittent travel to Mexico presented to the emergency room with two weeks of abdominal pain, which included two episodes of hematemesis. She appeared thin, with low muscle mass, and her abdominal examination revealed distension, tenderness, ascites, and a fluid wave. Vitals included a heart rate of 110 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 89/55 mmHg. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (white blood cell count 14.9 K/uL), anemia (hemoglobin 9.9 g/dL), and significantly elevated urea (43 mg/dL) and ferritin (4464 ng/mL). Liver function tests, metabolic panel, and coagulation profile were normal. Paracentesis gram stain and culture, as well as cytology and other fluid studies were within normal limits. CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 5 x 10 x 9 cm multilobulated hyper-enhancing mass in the gastric body/antrum, with erosion into the adjacent transverse colon. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy confirmed Cytomegalovirus (CMV) gastritis. Notably, the Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) stain was negative. She was discharged from the hospital medicine service after a one-week admission with a two-week course of oral valganciclovir and a proton pump inhibitor. A repeat EGD three months later showed improvement in gastric erosions, and CT showed an interval decrease in the size of the gastric mass.

Discussion: The differential for abdominal pain and hematemesis is extensive, with bleeding varices a concern in decompensated cirrhosis. Imaging suggested malignancy such as gastric adenocarcinoma, but infectious etiologies, such as tuberculous gastritis, histoplasmosis, CMV and H. pylori, were also considered.CMV, a virus in the herpesvirus family, can reactivate in immunocompromised hosts, leading to gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain and bleeding. In this patient, CMV infection manifested as an ulcerated exophytic mass in the gastrointestinal tract. The virus can also trigger acute gastric mucosal lesions and lead to chronic inflammation, with the development of pseudotumors. Diagnosis in cases of gastric masses hinges on endoscopic evaluation and histopathology to exclude H. pylori gastritis or malignancy. While both CMV and H. pylori can cause gastritis, their management differs significantly. CMV may improve with proton pump inhibitors alone, while H. pylori requires antibiotics. Endoscopic findings in CMV gastritis, such as punched-out ulcers and necrotic mucosa, are distinctive. Cytomegalic cells with basophilic inclusions (“owl’s eyes”) are highly specific for CMV. In contrast, H. pylori-related ulcers typically exhibit more uniform appearances with chronic changes. Distinguishing between these two gastric conditions is crucial for appropriate treatment. Although serum testing and polymerase chain reaction may suggest CMV, in early infection they may not be reliable and thus biopsy is critical for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusions: This case demonstrates the importance of broadening the infectious differential for gastric ulcerations and masses. CMV can manifest in multiple ways in the gastrointestinal tract, with symptoms resembling gastric cancers and infections such as Helicobacter pylori. Even in immunocompetent patients, consideration of CMV and other herpesviruses with a predilection for the alimentary tract is important for clinicians considering the need for urgent EGD evaluation.