Background:

The patient‐physician relationship is complex, often infused with a number of intangible factors. Several studies have reported that physician attire may be an important and modifiable determinant of a patient’s trust, confidence and satisfaction in their physician. Because the context and urgency of care, patient and physician factors and cultural beliefs may all influence patient perception, these dimensions must be considered when examining the influence of attire on patients. Additionally, an in‐depth understanding of what elements of attire influence patient perception is necessary to inform policy recommendations regarding physician attire. We therefore systematically reviewed the literature to understand the influence of physician attire on patient perceptions.

Methods:

Multiple databases including MEDLINE via Ovid (1950–2013), Embase (1946–2013) and Biosis Previews via ISI Web of Knowledge (1926–2013) were searched for pertinent keywords. Studies published in full‐text, abstract or poster form were eligible for inclusion. No publication date, language or status restrictions were placed and study authors were contacted for missing data. Two authors independently determined study eligibility and independently evaluated risk of bias using a modified Downs and Black scale. Studies were included if they (a) evaluated physician attire; (b) reported patient‐centered outcomes such as satisfaction, perception, trust, attitudes, or comfort; and, (c) studied the impact of attire on these outcomes. We excluded studies involving pediatric and psychiatric patients.

Results:

Of 1,011 citations, 42 abstracts met inclusion criteria. Following exclusion of duplicate and ineligible articles, 29 studies were included in the systematic review. Included studies featured patients from internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics, family practice, dermatology, podiatry and orthopedics. The context of care varied and included medical and surgical clinics, emergency rooms, hospital wards, private practice, urgent and intensive care units, and military‐based clinics.

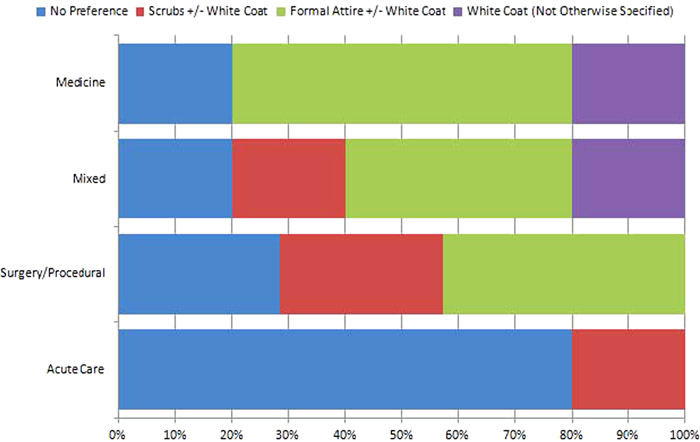

Of the 29 studies, 12 surveyed patients following a clinical encounter whereas 17 surveyed perceptions only using descriptions or pictures of various attire. When patients were surveyed based on a clinical encounter, only 25% of studies reported that physician attire influenced their perception of their physician, all preferring more formal attire. Patients who only received text or pictures of attire without a clinical encounter, however, were more likely to offer preferences. Patients older than approximately 45 years of age and those seen in internal medicine settings preferred formal attire with a white coat compared to younger patients. In acute care settings, patients were generally either indifferent to attire or preferred scrubs (Figure 1).

Conclusions:

The impact of attire on patient satisfaction, trust and comfort is complex and likely context‐specific. Our review suggests that older patients appear more likely to prefer formal attire than younger patients, and formal attire in critical and acute care settings appears less important than in primary care encounters. Our study suggests that when caring for older patients or patients seen in primary care, formal attire may be more relevant as an intervention to improve patient satisfaction, trust and rapport. Policies that account for these important nuances along with future studies that better assess patient impact in various clinical settings are necessary.