Background: Reflective writing has been increasingly incorporated into pre-clinical medical education as a means to increase empathy, foster professional development, and encourage well-being. [1] However, not all students inherently enjoy writing, and many may not have the opportunity to debrief on emotionally charged experiences with classmates during the clinical years. In addition, the topics on which the students choose to reflect may represent areas that are important to address within the clerkship curriculum. We introduced a mandatory reflective exercise for third-year medical students in the inpatient medicine clerkship that included a peer-driven discussion and then assessed the thematic content of their pieces.

Purpose: To examine the value of peer-driven discussions of reflective pieces for third year medicine clerkship students and to perform content analysis to inform future debriefing opportunities

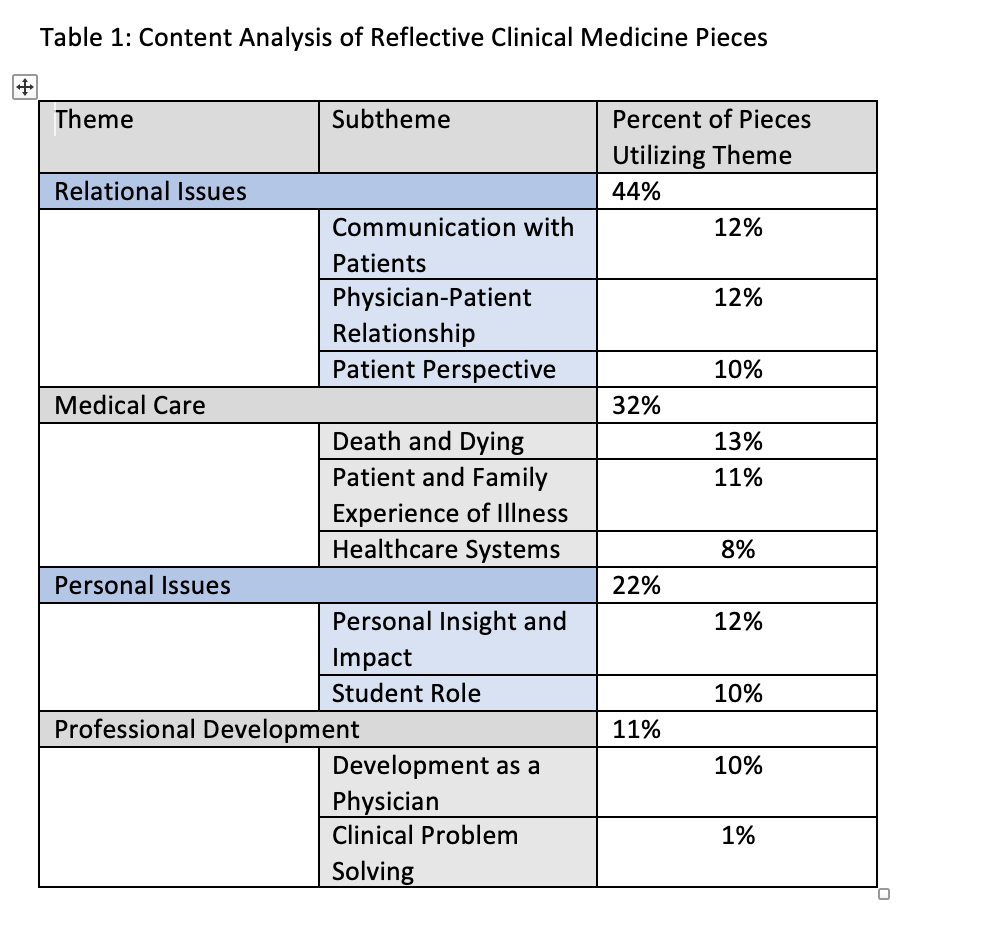

Description: Students created a reflective piece regarding their experience on the clerkship. Submissions could be prose, poetry, photography, or any other expressive form. Reflective pieces were subsequently distributed to the clerkship cohort who met for an hour-long, student-driven discussion about the pieces with assistance from a faculty moderator. Following the discussion, students completed an anonymous survey regarding workshop perceptions. We used qualitative content analysis to explore themes within students’ reflective pieces. The themes were selected from a previously published qualitative assessment of students’ reflective writing and included four major topics and ten subtopics. [2] The pieces were reviewed by two of the authors and a third author resolved any differing selections. 91 students completed the workshop with an 82% survey response rate. 38% of students had never before used creative techniques as a form of professional reflection. Students found the small-group discussion more enjoyable than the creative process (72% vs 39%). They noted the “open and honest,” “cathartic” discussion as a strength, with one student commenting, “…. revealed that we are often not alone in our emotions regarding our experience in the clerkship.” In content analysis (Table), 44% of the pieces focused on relational issues, 32% on medical care, 22% on personal issues, and 11% on professional development. Common subthemes were death and dying (13%), communication with patients (12%), the physician-patient relationship (12%), and the student role (10%).

Conclusions: By a sizeable margin, students found the subsequent small-group discussion more valuable than the creative process itself, implying that reflective exercises are more constructive in conjunction with group sessions that provide an opportunity for students to debrief and receive support from their peers. To our knowledge, this has not previously been reported in the literature. Comments from students suggested that the informal space to share their emotions was well-received, and they appreciated being able to express themselves in mediums beyond writing. Their focus on certain themes, including communication with patients or death and dying, suggests that clerkship students may benefit from formal debriefing opportunities regarding these topics, and institutions should assess their curriculum to assure they are addressed. Consideration should be given to adding peer discussion groups to open-form reflective workshops as a means of supporting students during this crucial time in their professional development.