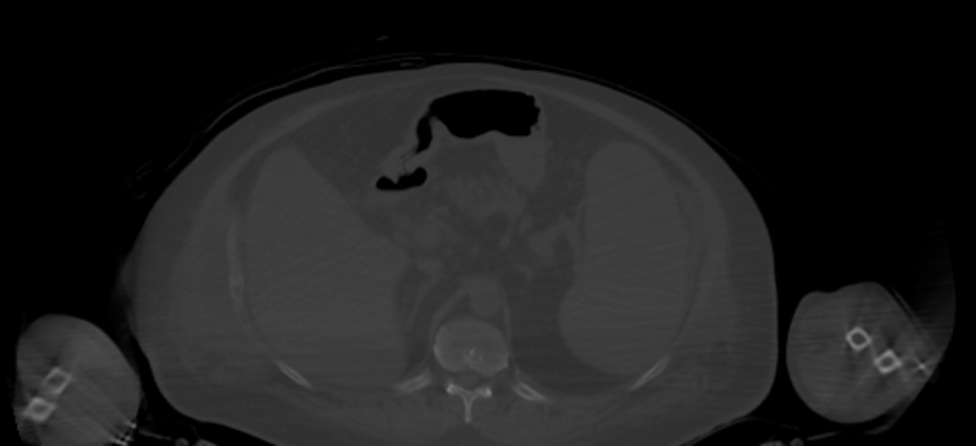

Case Presentation: A 65-year-old male with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) on immunosuppressive therapy, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension presented with fevers, abdominal pain, and generalized weakness. He was also noted to have a 40-pound weight loss over two months. He was recently admitted the month prior for mastoiditis and again two weeks earlier for similar symptoms. In previous hospitalizations, he underwent a significant infectious disease and malignancy workup, including a negative bone marrow biopsy and computed tomography imaging of chest, abdomen, and pelvis which was overall normal with exception of hepatomegaly. This admission, lab workup was generally unrevealing, except for mild elevations in liver transaminases, peaking at 207 U/L for AST, 203 U/L for ALT, and 1,548 U/L for alkaline phosphatase, and anemia and thrombocytopenia to nadir 9.2 g/dL and 47 × 10^3/uL, respectively. Hepatology was consulted and recommended obtaining liver biopsy to rule out infiltrative processes, including sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, or malignancy; this ultimately revealed large B-cell lymphoma. Interestingly, positron emission topography (PET) of his whole body showed metabolic mediastinal lymphadenopathy and hypermetabolic appendicular skeleton suggesting bone marrow hyperplasia (despite previous negative bone marrow biopsy), and normal liver activity (Figures 1, 2). One week later, after finishing his first chemotherapy induction, he went into multi-organ shock that was nonresponsive to multiple pressors, and subsequently passed away after shared decision making with his family.

Discussion: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is known for its aggressive progression and typically manifests with systemic B symptoms and rapidly growing lymph node masses or extra-nodal involvement. However, in this patient, the clinical presentation was masked by overlapping symptoms from chronic illnesses, such as IPF and recurrent infections. These comorbidities created a diagnostic blind spot, delaying recognition of the malignancy. The absence of classic imaging findings such as generalized lymphadenopathy further obscured the diagnosis. In addition, his chronic immune compromise due to IPF may have lead to the development of lymphoma. This case underscores the need for heightened clinical vigilance in evaluating systemic symptoms in patients with chronic comorbidities. Repeated diagnostic evaluations are critical when systemic symptoms persist or worsen, even after negative workups. It also raises questions regarding the role of chronic immune dysregulation in the pathogenesis of lymphomas in patients with chronic illnesses. This case illustrates the complexities of diagnosing malignancies in the context of comorbid disease and the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for malignancies like DLBCL in high-risk patients. Recognition of this diagnostic challenge is essential for timely diagnosis and treatment, which are critical to improving patient outcomes.

Conclusions: This case underscores the challenges of diagnosing aggressive malignancies like DLBCL in patients with overlapping chronic illnesses. It highlights the importance of re-evaluating unexplained or worsening symptoms in high-risk patients, even after recent negative findings. This case also raises potential questions regarding the impact of chronic infections and immune compromise on the lymphoma development in similar patient populations.