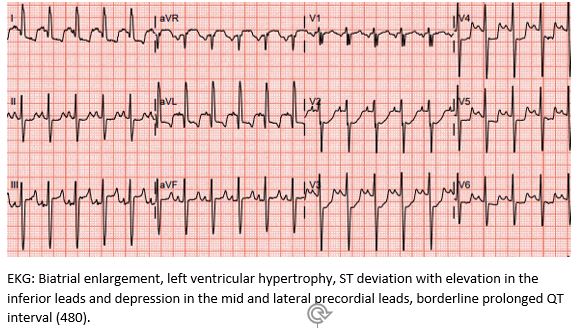

Case Presentation: 1 year old otherwise healthy twins present to the ED after Twin A became acutely unresponsive. The twins had been ill with a GI virus with fever, vomiting, and decreased activity for a week. The night of presentation, Twin A started vomiting, developed perioral cyanosis, and became unresponsive. On arrival to the ED, a code was called when he was unarousable and bradycardic to 34. During resuscitation, he developed leftward eye-deviation and received a dose of Ativan for presumed seizure. He remained bradycardic despite CPR so he was intubated, started on vasopressors, and admitted to the PICU. Initial trauma workup negative; however, prior to admission his brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was noted to be 15,428 and EKG was abnormal.As the cause of Twin A’s bradycardic arrest was unknown, family brought Twin B to the ED for evaluation. After initial evaluation, he was admitted to the hospitalist service. Etiologies causing altered mental status and bradycardic arrest in only 1 twin were considered – including ingestion, trauma, and electrolyte abnormalities. Initial labs showed normal electrolytes and negative drug screens. Twin B’s BNP was comparatively less elevated at 8260 but his EKG was more abnormal than brother’s with ST deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy in addition to the atrial enlargement and prolonged QTc seen on brother’s EKG. (Figure 1)Given the elevation of both twins’ BNP and abnormal EKGs, the hospitalist team was concerned for cardiac etiology secondary to genetic or viral causes. Echocardiograms showed dilated atria with normal ventricular sizes and preserved systolic function. The clinical constellation was consistent with restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) with acute decompensation.The twins were found to have a “variant of uncertain significance” on the DES gene. The DES gene codes for desmin, a protein in striated muscle such as myocardium, and other mutations in the gene cause dilated and restrictive cardiomyopathy.

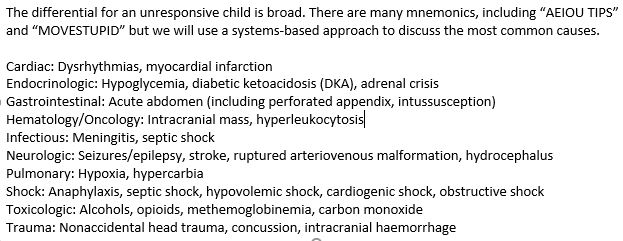

Discussion: When a child is unresponsive in the ER, the most important task is assessing their Airway, Breathing, and Circulation. After stabilization, the workup should include thorough physical evaluation for trauma; labs including glucose, electrolytes, urine drug screen; and an EKG. Once the child is admitted to the floor, the pediatric hospitalist must be comfortable continuing the work-up. A broad differential is included in Figure 2. Pediatric cardiomyopathies are a rare category of diseases, with an annual incidence of 1.1 per 100,000 children. All cardiomyopathies are defined by changes to the myocardium that lead to systolic or diastolic function, arrhythmias, or sudden death. The major categories are dilated, hypertrophic, and restrictive – with restrictive being the least common but with a poor prognosis (non-transplant 5-year survival of 22%). While there have been a number of case reports of familial RCM, few gene mutations have been confirmed, and even fewer patients have a known mutation. As more patients are tested, there is hope a more comprehensive gene panel will be created.

Conclusions: While this case demonstrates an extremely rare etiology, admission of a pediatric patient following an acute decompensation from an unknown cause is not. As many laboratory and imaging modalities are ordered after admission, it is imperative that pediatric hospitalists consider a broad differential when evaluating the initially unresponsive patient, including cardiac etiologies.