Background: The strongest risk factor for readmission to the hospital and failure to successfully return to the community after hospital discharge is impaired physical function. Although published experience with wearable devices in post-acute care settings is scant, measurement of steps in other care settings has been shown to be feasible and directly linked with post-discharge outcomes. This study is the first to our knowledge to measure mobility in home health patients (an important cohort since the use of home health reflects need for continued physical and/or occupational therapy) using wearable devices and use principles of behavioral economics to encourage mobility. The primary objective of this study is to determine usability and feasibility of these devices, and to provide baseline knowledge to address the need to improve mobility upon hospital discharge.

Methods: The study was a two arm, 8-week pragmatic pilot randomized trial of a behavioral economics intervention, to increase mobility in Veterans age 60 or older receiving home health (HH) services at hospital discharge. Participants were randomly assigned to a behavioral economics intervention using principles of loss aversion and gamification vs. a control group through a number generator following enrollment. Participants were sent home with an ActivPAL actigraphy device and a pedometer to monitor their activity and step count. Participants were texted to input their step counts recorded by the pedometer on a daily basis to the VA’s electronic medical record using the Annie program, while the ActivPAL recorded continuously for three weeks and then was replaced with a new device. The intervention continued and outcomes were measured at 60 days post-discharge. We compared mean step counts from first to the last week of complete data.

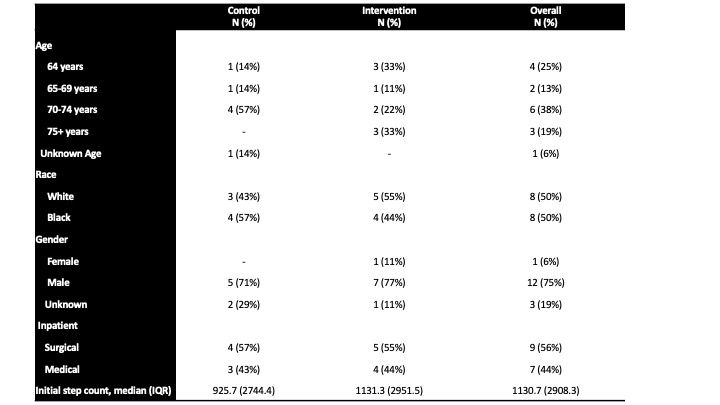

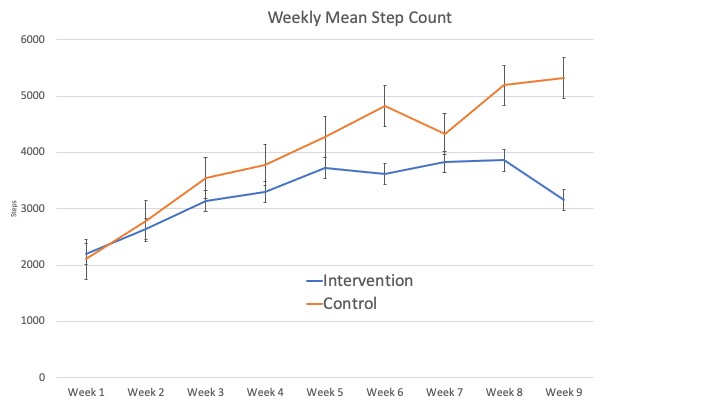

Results: Thirty-seven Veterans consented to the study; nine self-revoked and twelve were withdrawn due to lack of follow-up, resulting in 16 Veterans completing the study (9 intervention, 7 control, characteristics in Table 1). Participants all reporting liking wearing the pedometer, while 3 did not like wearing the ActivPAL. The pedometer data was more complete (4% missing versus 24% missing using ActivPAL). Initial step counts were low in both groups (median of 926 in control [IQR 2744], 1131 [IQR 2952] in intervention). Both groups increased their steps over the study period, although the control group increased steps more than the intervention group overall (+3221 steps in control vs + 959 in intervention, Figure 1). Medical and surgical patients were evenly balanced between groups; surgical patients exhibited larger increases in steps (medical: +2455, surgical: +2936).

Conclusions: We found that – as expected – retaining study participants in post-acute care was difficult, which has important implications for future interventions. Surprisingly, we found participants both reported more complete data and enjoyed using a waist-worn pedometer compared to the ActivPAL, which uses an adhesive sleeve to attach to the thigh. We are analyzing the correlation between ActivPAL and pedometer data. This trial was not powered to compare differences in step counts, and the very large ranges in initial step count and change in step count across the study population suggests larger samples are needed to determine intervention efficacy. Thus, in addition to providing information regarding feasibility of the trial and usability of devices, this study also provides important baseline information for powering a subsequent trial.