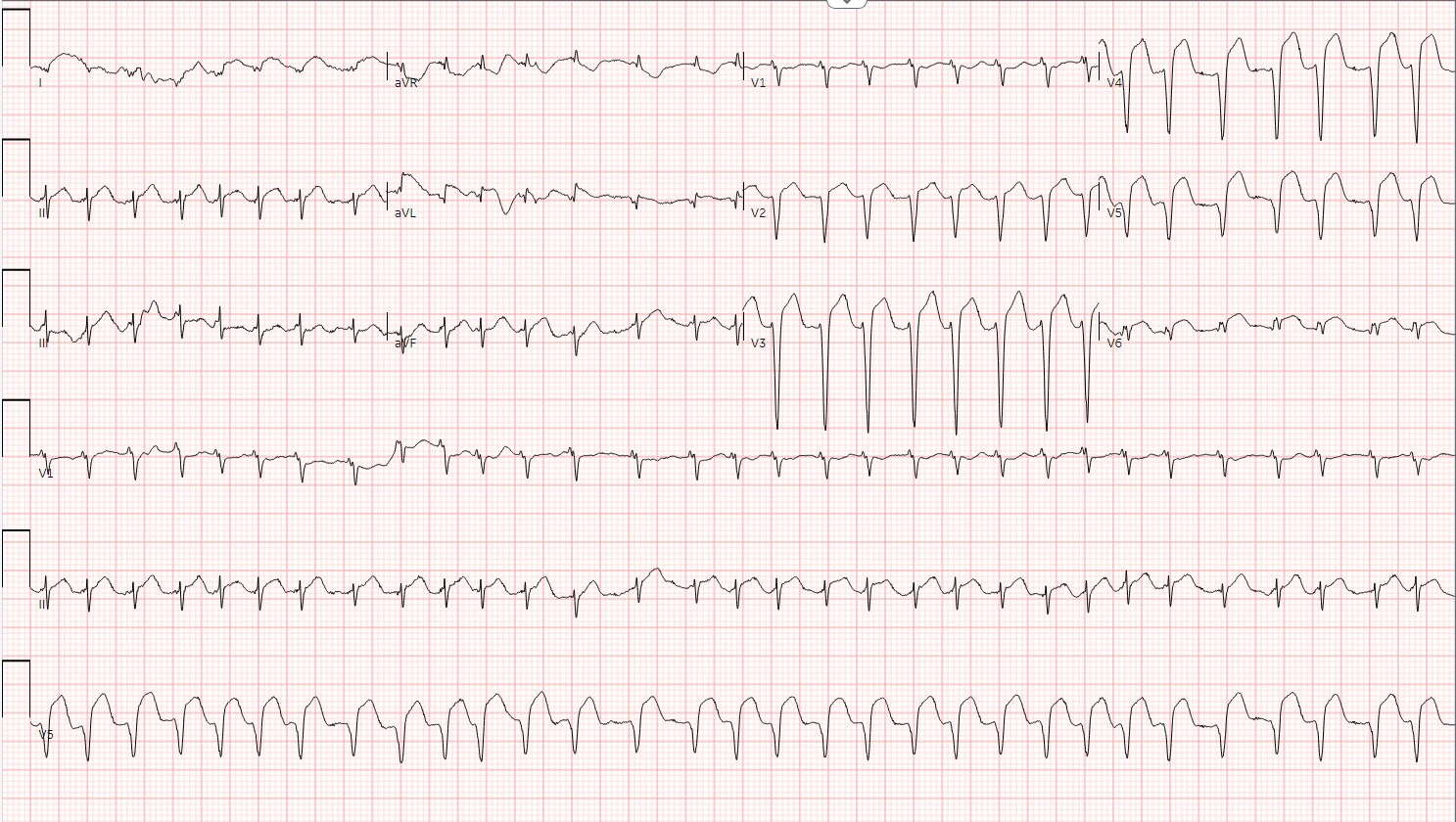

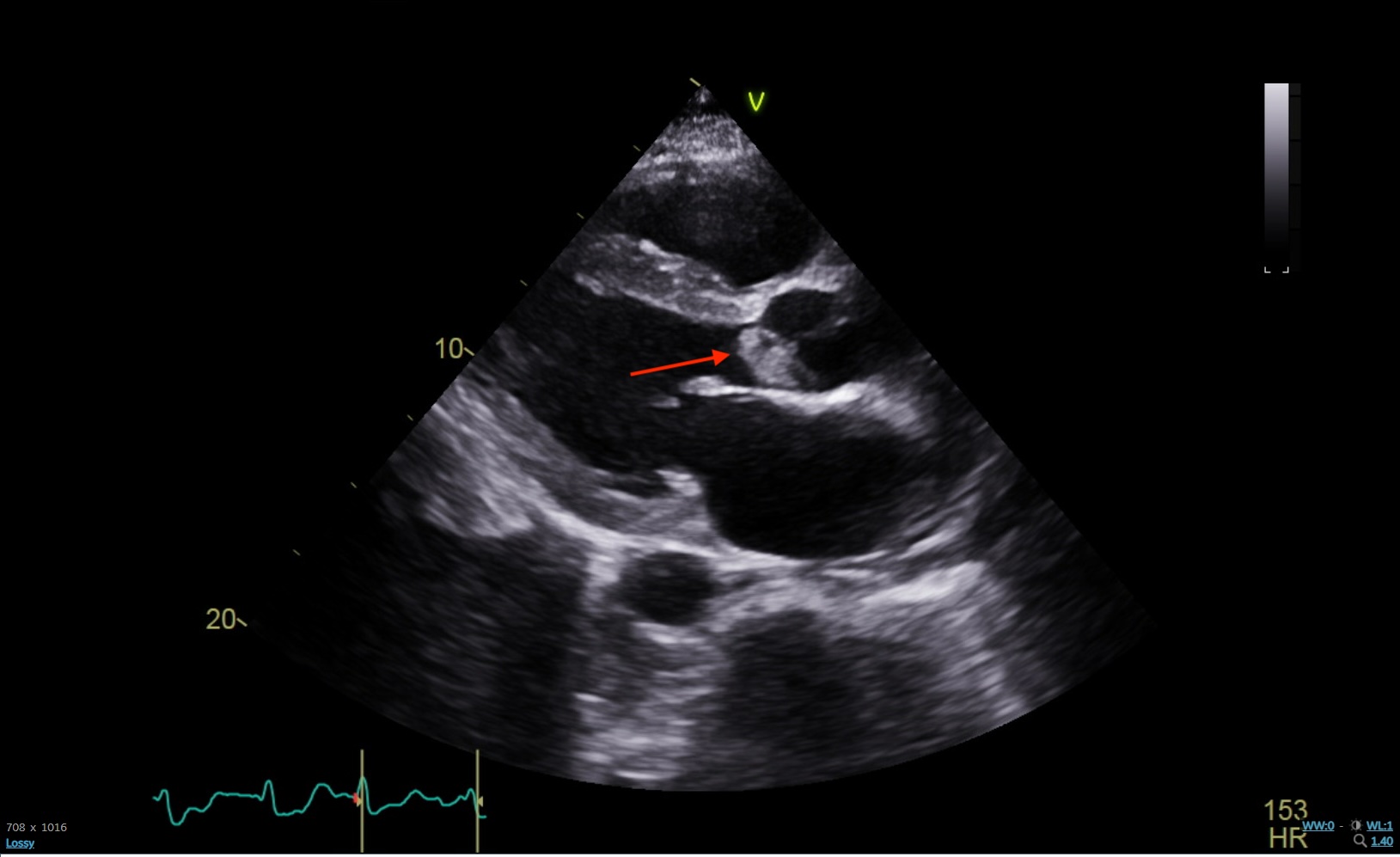

Case Presentation: A 44-year-old male with a history of opioid use disorder and intravenous drug use (IVDU) presented to the emergency department with chest pain and malaise. On presentation, his temperature was 103.3 degrees Fahrenheit, blood pressure was 86/58 mmHg, and heart rate was 157 beats per minute. The initial electrocardiogram showed multi-lead ST-elevations and atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed which showed a large vegetation on the aortic valve. Blood cultures grew Streptococcus species. Intravenous antibiotics, amiodarone, and heparin drip were started. Sinus rhythm was achieved temporarily but was difficult to maintain due to the patient’s underlying sepsis. Both the interventional cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery teams evaluated the patient for possible coronary reperfusion procedures or valvular surgery. Ultimately, he was deemed a poor candidate for either due to the following: his unstable clinical status, given his hypotension and rapid ventricular response; lack of reliable social support, since the patient would require multiple follow-up appointments; and history of medication nonadherence, as the patient would likely require lifelong medications. Medical therapy was continued until the patient could be stabilized; however, he then left the hospital against medical advice and was lost to follow-up. Though coronary angiography was unable to be performed for this patient, the most likely clinical diagnosis for this case is coronary embolism causing ST-elevation myocardial infarction from infective endocarditis. The patient’s relatively young age, lack of atherosclerotic risk factors outside of male gender, normal LDL, history of IVDU, and ST-elevation in multiple leads suggestive of multivessel involvement all point toward this diagnosis.

Discussion: Coronary artery embolism (CE) is a nonatherosclerotic cause of ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. The prevalence ranges from 4% to 13%, and there is a high associated morbidity and mortality rate. The most common underlying cause in patients with CE include atrial fibrillation, followed by dilated cardiomyopathy and endocarditis. Among patients diagnosed with CE, there is a higher incidence of cardiac death compared to patients with myocardial infarction not caused by CE. Treatment guidelines for ST-elevation myocardial infarction secondary to septic emboli are not well-established but include interventional reperfusion strategies such as primary angioplasty with balloon and stent, stent implantation, manual thrombectomy without angioplasty, guidewire without angioplasty or thrombectomy, and medical therapy with antithrombotic drugs. The decision for treatment modality can depend on the stability of the patient, other underlying or ongoing medical conditions, number and location of occlusions, and socioeconomic barriers, to name a few.

Conclusions: Decision-making for the treatment of STEMI secondary to CE from infective endocarditis is complex and multifactorial. This patient’s hemodynamic instability, concurrent atrial fibrillation, lack of source control of the infection, and social barriers can limit treatment options.