Background: For most infections, shorter antibiotic durations are similarly effective to longer durations but have lower risk for side effects and antibiotic resistance.1-9 Since 2019, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) guidelines have recommended hospitalized patients with CAP be treated until clinical “stability and for no less than a total of 5 days.”10 However, randomized clinical trials have found that, in patients with CAP who stabilize by hospital day 3, very short antibiotic durations (e.g., 3-days) are non-inferior to longer durations.11 How these trial results could and are impacting real-world practice is unknown.

Methods: Using a 68-hospital cohort study of hospitalized, general care adults with CAP, we aimed to a) quantify the proportion of hospitalized, general care patients who—according to trial criteria11—qualify for a 3-day antibiotic duration, b) quantify the proportion of hospitalized, general care patients who actually receive a 3-day antibiotic duration, and c) assess the difference in 30-day patient outcomes between patients eligible for a 3-day duration who received a very short (i.e., 3-4 day) vs. longer (≥5 day) duration. Patients were considered to have CAP if they had a pneumonia discharge diagnosis, received antibiotics on hospital day 1 or 2, had positive imaging, and had ≥2 signs/symptoms of CAP. Patients with concomitant infections (including COVID-19), admission to intensive care, pregnancy, or severe immune compromise were not included.

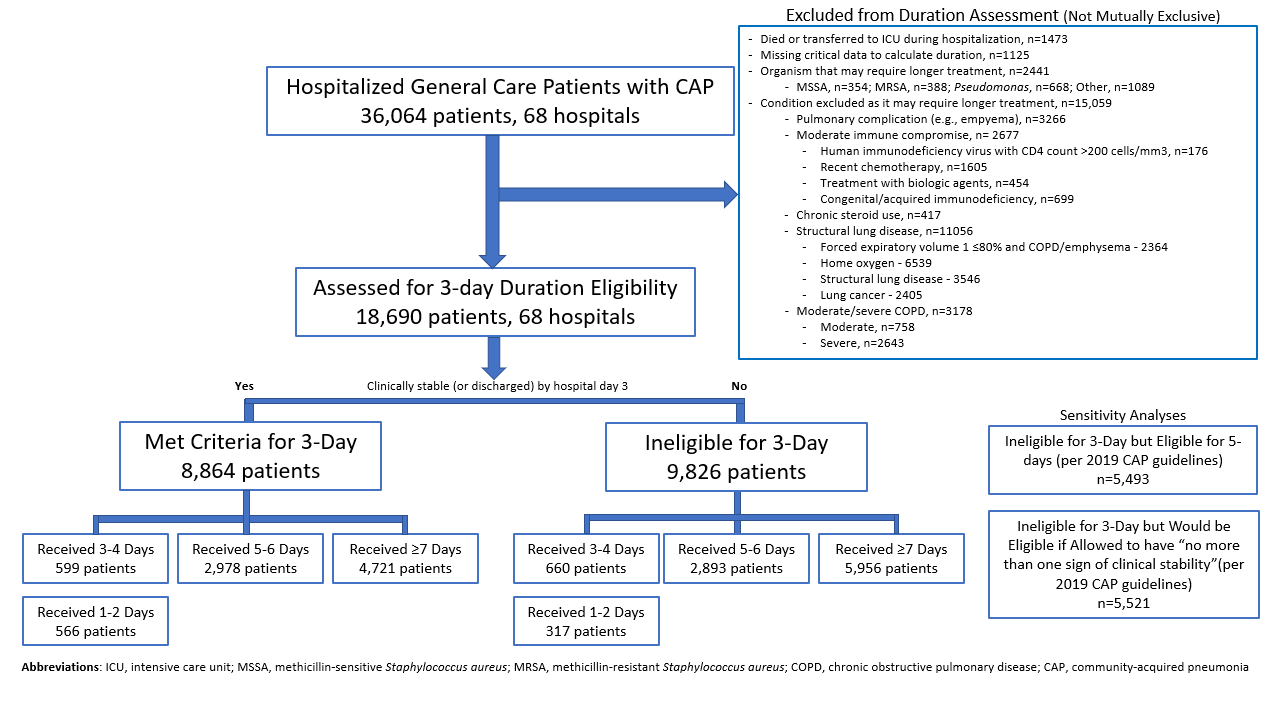

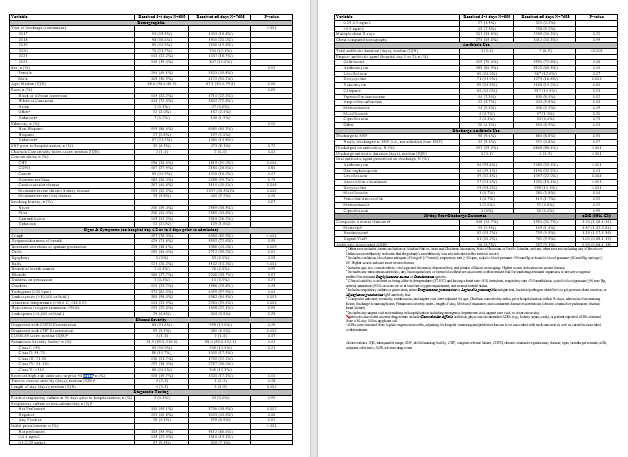

Results: Between 2/23/2017 and 8/3/2022, 36,064 patients with CAP across 68 hospitals were included. Of those, 48.2% (9,826/36,064) were excluded because they had a condition or organism that is ineligible for a 3-day duration (see Figure 1 for details). Of the 18,690 patients remaining, 52.6% (9,826) were still unstable on hospital day 3 and thus ineligible for a 3-day duration. Therefore, of all hospitalized patients with CAP, only 24.6% (8,864/36,064) would be eligible under trial guidelines for a 3-day duration. Notably, 55.9% (5,493/9,826) of patients unstable on day 3 would be eligible for 5-days of therapy under current guidelines. In practice, use of 3-4 day duration was rare occurring in only 6.8% (599/8,864) of patients actually eligible for a 3-day duration vs. 6.7% (660/9,826) of patients who were unstable on hospital day 3 (P=0.945). Use of 3-4 day duration increased over time and comorbidities that could mimic CAP or a negative procalcitonin were more common in patients who received a 3-4 day duration whereas specific symptoms of CAP were less likely (Table 1). After adjustments, patients eligible for a 3-day duration who received a 3-4 day vs. ≥5 day duration had higher odds of 30-day mortality (aOR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.32-2.64) and readmission (aOR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.17-1.56).

Conclusions: In this 68-hospital cohort study, less than a quarter (24.6%) of all general care patients hospitalized with CAP would be eligible for a 3-day antibiotic duration, less than the 44% reported in trials. Though increasing over time, there was very little use of 3-4 day durations and, when very short durations were prescribed, outcomes were worse potentially due to CAP misdiagnosis. Given the small number of patients eligible for 3-day therapy, and the potential harm with too short durations, it may be prudent to focus on increasing appropriate use of 5-day antibiotic durations.