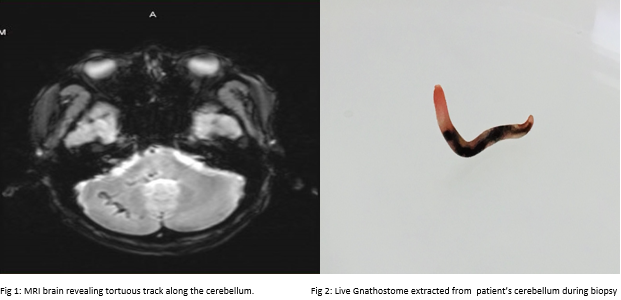

Case Presentation: A 49-year-old Thai male with no past medical history presented after one-week of progressive left arm pain, numbness, and weakness that radiated to his neck. The patient was a chef who had immigrated to the United States five years previously with no return travel to Southeast Asia. His lab work was largely unremarkable except for an absolute eosinophil count of 2134. His neurological exam was initially normal, but on hospital day three, he developed paraplegia, urinary retention, and sensory deficits below the mid-thoracic level. A lumbar puncture revealed >1700 white blood cells, of which 75% were eosinophils. Testing for parasitic worms native to the United States was negative. On hospital day five, a repeat brain MRI revealed what was thought to be multiple tortuous vessels with surrounding edema within the medulla and right cerebellum. Biopsy of the cerebellum was performed, and a live gnathostome was extracted. Unfortunately, despite treatment with albendazole and steroids, the patient continued to deteriorate and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Following the brain biopsy, he developed obstructive hydrocephalus and an external ventricular drain was placed. At this point, he had no gag reflex and his pupils were fixed, and his family decided to withdraw ventilator support.

Discussion: Gnathostomiasis is endemic to Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand and Japan1. Humans become infected by eating undercooked meat (usually fish, eel, poultry, or snake) or by drinking water containing larvae2. The cutaneous form of gnathostomiasis most commonly presents with eosinophilia and migratory cutaneous swellings associated with pain, erythema, and pruitis1. These typically begin three to four weeks after ingestion of the parasite, though they can appear months to years later2. Less commonly, larvae can migrate to the central nervous system which can present with sudden onset severe radicular pain and paresthesias, which is closely followed by paralysis3. A diagnosis of gnathostomiasis is made by clinical presentation, exposure history, and pronounced peripheral blood eosinophilia. Serologic tests have been developed but are not available in the United States4.Surgical excision, when possible, is the treatment of choice for cutaneous gnathostomiasis. When surgical removal is not feasible, albendazole is the drug of choice5. Ivermectin is more easily tolerated but is less effective6. The treatment of central nervous system gnathostomiasis infection is supportive, and we are uncertain whether treatment with corticosteroids or albendazole is beneficial7.

Conclusions: Though rare, with the increase of international travel and immigration from endemic areas, clinicians need to be aware of parasitic infections and their potentially devastating consequences.