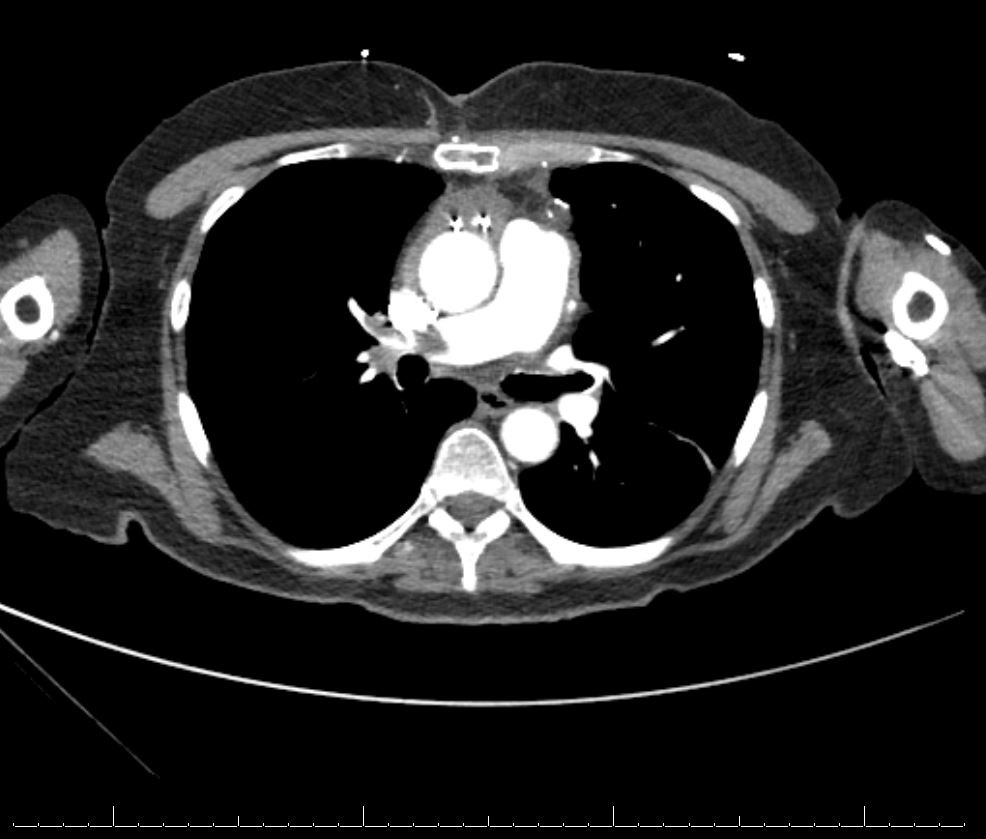

Case Presentation: A 66 year old female with a past medical history of hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia (HLD) and coronary artery disease (CAD) presented to the hospital for an elective three-vessel coronary artery bypass graft involving the left internal mammary artery to left anterior descending artery, saphenous vein graft (SVG) to the obtuse marginal artery, and SVG to the posterior descending artery. During the CABG, she received 2700 units of heparin. On post operative day (POD) seven she was discharged home. On POD nine, the patient presented back to the emergency department with pain, swelling, and erythema to the left lower extremity. An ultrasound of her lower extremities revealed an occlusive clot burden from the left popliteal to the common femoral vein. A heparin drip was initiated. A Chest CT was obtained with angiography and revealed an acute large burden, occlusive and non-occlusive pulmonary embolisms (PE), and associated right heart strain. The pulmonary embolism response team (PERT) was activated, and the patient underwent urgent mechanical thrombectomy by interventional radiology. Interestingly, initial lab work revealed a decrease in platelets from 209 on her previous discharge to 82 at the time of re-presentation. The combination of thrombosis and thrombocytopenia raised the concern for heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). A HIT Expert Probability (HEP) score was calculated and found to be elevated. The initial heparin drip was stopped and she was transitioned to Fondaparinux. A HIT antibody screen and serotonin-release assay (SRA) subsequently confirmed the diagnosis.

Discussion: CABG remains a common procedure with close to 400,000 procedures performed each year (1). The rate of HIT amongst this population of patient undergoing CABG has been reported as high as 0.3-1% (2). Mortality from HIT in the setting of CABG has been reported to increase by 50% in the early postoperative setting (2). Thrombocytopenia following CABG is common and has been reported as high as 8% with multiple potential etiologies (2). The initial evaluation of new onset thrombocytopenia can differ based on time of presentation. A patient that initially presents with thrombocytopenia can have a different differential diagnosis than the patient that has already been hospitalized for a period of time and then develops thrombocytopenia. The latter is often related to a medication side effect or sequelae of presenting illness. The former has a much broader differential diagnosis (3). This case posed an additional challenge to diagnosis given the interruption in contact with the healthcare system. This case highlights the importance of: 1) performing a thorough history and chart review during any new encounter, 2) maintaining a high index of suspicion for HIT in thrombocytopenia following CABG given the relatively common nature of the complication, and 3) recognizing the nuanced differential diagnosis of a patient that is both coagulopathic and thrombocytopenic.

Conclusions: Given the relatively high rate of HIT and potential severe morbidity and mortality associated with delayed or missed diagnosis, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for this disease in thrombocytopenic patients following CABG. The patient in this case was able to be transitioned from Fondaparinux to Eliquis for continued outpatient treatment of HIT. Heparin was added as a severe allergy to her allergy list on the electronic medical record. Follow up was arranged with her primary care physician, hematology, and cardiovascular surgeon