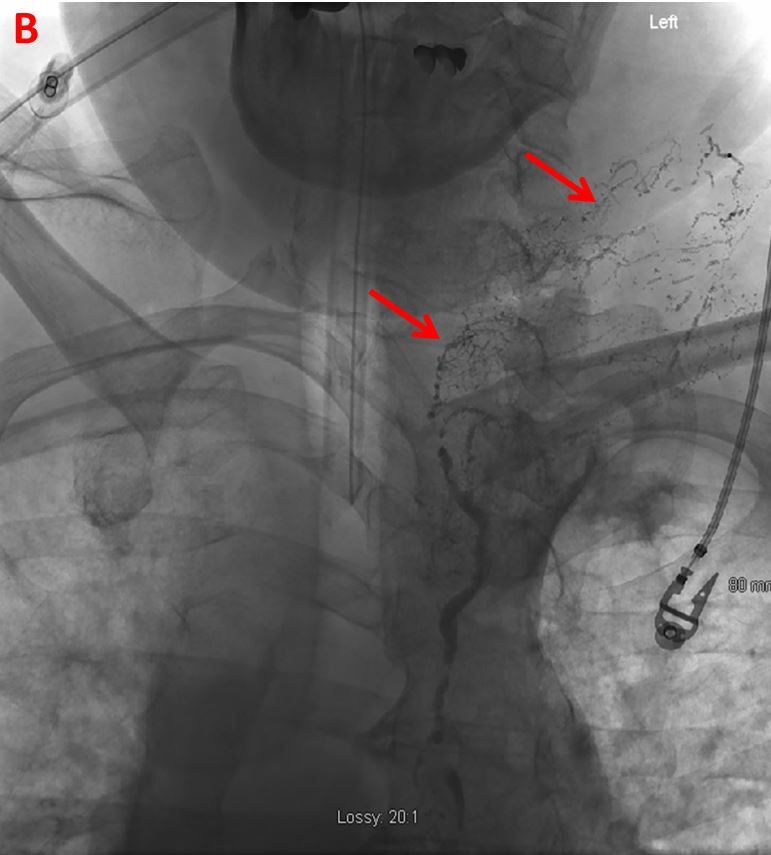

Case Presentation: The patient is a 56-year-old Caucasian male who presented from an outside hospital (OSH) for recurrent chylous ascites. Four years ago, he was diagnosed with unprovoked left subclavian and left internal jugular deep vein thromboses (DVTs) and had been placed on chronic warfarin therapy. At that time, he developed chylous ascites which resolved after one paracentesis. Now, two months prior to our encounter and four months after spontaneously stopping warfarin, he reported increasing dyspnea and abdominal girth over the span of three weeks. Past history was notable for left subclavian and left internal jugular DVTs, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea and a distant hernia repair. Workup at the OSH included an unremarkable echocardiogram, bilateral lower extremity Dopplers negative for a DVT, and CT thorax, abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast which showed abdominal ascites. Groin lymph node biopsies revealed no evidence of a malignancy. Even after resuming anticoagulation, initiating diuretics and Octreotide, and maintaining a low-fat diet, the patient underwent multiple paracenteses. At our hospital, physical exam was notable for a distended abdomen with moderate ascites. Chemistry analysis of the abdominal fluid indicated chylous ascites (triglyceride level 1,210 mg/dL) without signs of infection and with negative cytology. Interventional radiology (IR) was consulted. A venogram of the left upper extremity showed occlusion of the axillary vein to the superior vena cava (SVC) with extensive venous collaterals. A lymphangiogram showed occlusion of the distal thoracic duct at the level of the subclavian vein with extensive lymphatic collaterals but no leak. Coil and glue embolization of the cisterna chyli and thoracic duct was subsequently performed. Upon interval follow-ups, the patient reported no further fluid accumulation in his abdomen and no recurrence of symptoms.

Discussion: Chylous ascites is a rare condition where lipid-rich fluid is found in the abdominal cavity. This occurs due to injury of the lymphatic system from trauma, malignancy-related obstruction, post-operative complications, infections, and, less commonly, chronically elevated central venous pressure secondary to a DVT. Treatment is targeted at the underlying cause. In our patient, chronic venous occlusion from his DVT caused increased thoracic duct pressure which then resulted in formation of a venous collateral drainage network. Abrupt cessation of anticoagulation likely led to microthrombi formation, thus worsening the pressure gradient. As a result, lymphatic fluid leaked into the abdominal cavity. By embolizing the cisterna chyli and thoracic duct, the aim was to redirect the lymphatic fluid to drain into the already formed collaterals that would then drain into veins other than the SVC. Few literature cases present chylous ascites stemming from a large DVT burden. Thus, this case is important for broadening of clinical knowledge and so that providers have an index of suspicion when such patients present in the clinical setting.

Conclusions: This case illustrated how an extensive DVT burden resulted in recurrent chylous ascites refractory to medications and dietary restrictions, but embolization and redirection of lymphatic fluid via a collateral lymphatic and venous network provided a novel approach to symptomatic relief.