Case Presentation: 37-year-old G2P1102 patient 4 months postpartum with history of persistent hypokalemia and pre-eclampsia with severe features superimposed on chronic hypertension presents to the ED with a few weeks history of persistent headache, generalized weakness, and an elevated blood pressure of 180/110. Patient was admitted for symptomatic severe-range hypertension and hypokalemia. Subsequent workup revealed metabolic alkalosis and elevated aldosterone-to-renin ratio. She responded well to spironolactone. Care team suspected primary aldosteronism (PA). However, CT adrenal and MRI abdomen reported left adrenal and retroperitoneal masses that were consistent with pheochromocytomas. Random catecholamine and normetanephrine measurements were negative, but a 24-hour normetanephrine was elevated. Upon discharge, patient’s follow up evaluation with urology returned with concern for the adrenal mass as pheochromocytoma while the retroperitoneal mass as an aldosteronoma. Patient subsequently underwent adrenalectomy and retroperitoneal mass excision. Surgical pathology for the adrenal mass showed an aldosteronoma while the result for the extra-adrenal mass was a pheochromocytoma.

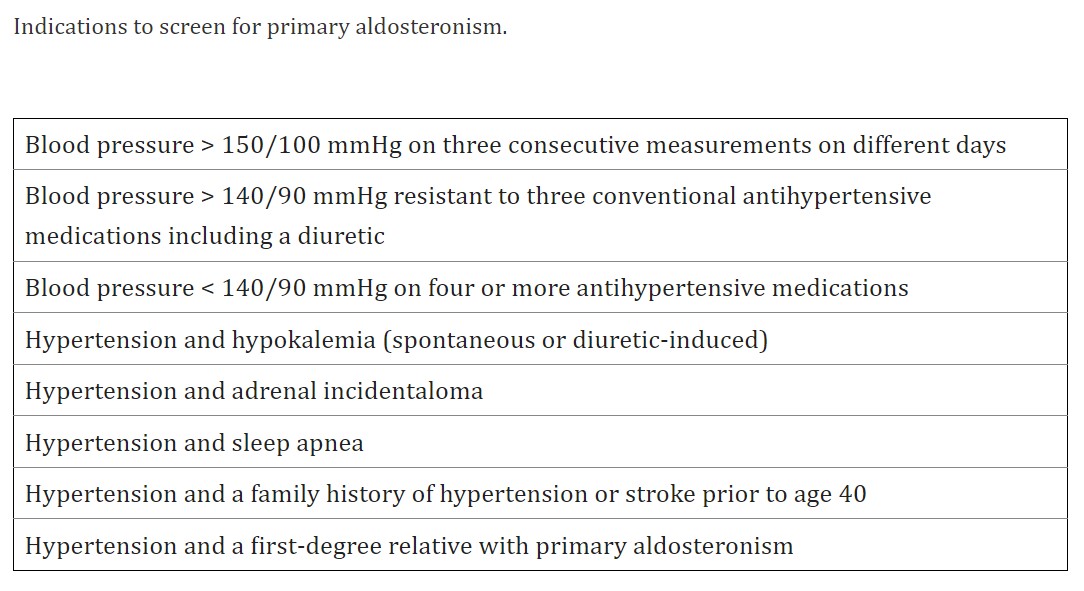

Discussion: This was a challenging case diagnostically. Many factors can complicate patient’s hypertensive state including her intrapartum diagnosis of pre-eclampsia with severe features superimposed on her preexisting chronic hypertension as well as physiologic and psychosocial changes associated with pregnancy and post-partum. It is unclear whether the patient’s pheochromocytoma and aldosteronoma were always present contributing to chronic hypertension, or these masses have developed during the course of patient’s pregnancy.In 2016, Endocrine Society published a list of indications to screen for PA (Table 1) which includes having hypertension and a family history of hypertension. Based on that indication alone, a high percentage of patients should be screened for PA. However, only a small fraction of them have been done so (1). Besides meeting the aforementioned indication, our patient also has long standing hypertension and hypokalemia, yet, she had never been screened for PA until this admission. During the workup, there was inconsistency between clinical and imaging findings. Patient’s triad of resistant hypertension, hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis was most consistent with primary hyperaldosteronism. Elevated aldosterone to renin ratio and the patient’s response to spironolactone further solidified the suspected diagnosis. However, both CT and MRI findings reported pheochromocytoma. Based on literature, about 80% of adrenal incidentalomas are nonfunctional adenomas, 9% cause subclinical Cushing’s syndrome, 4% are pheochromocytomas, and only 1% are aldosteronomas (2). Our patient has both active lesions which is extremely rare.

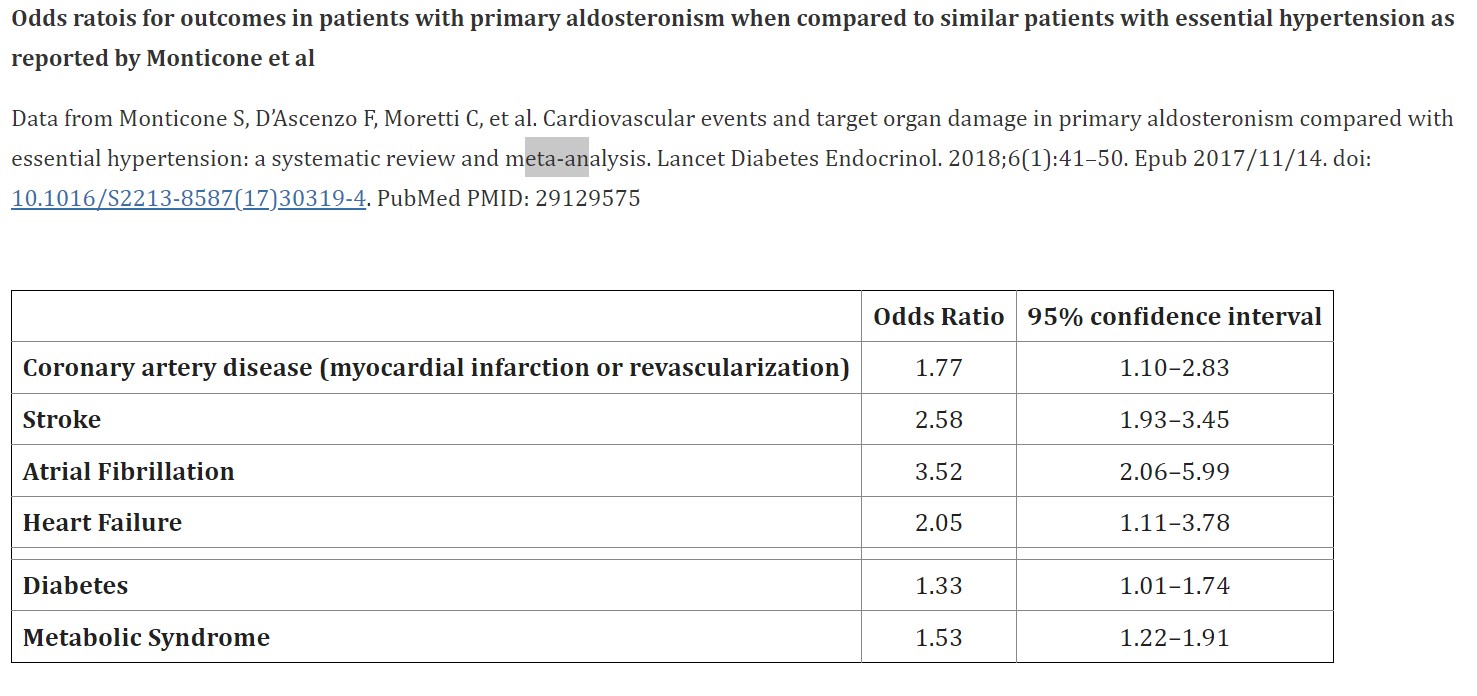

Conclusions: Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are a major risk factor of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Most cases of hypertension in pregnancy are due to essential hypertension. Secondary causes, such as endocrine and renal disorders, are rare with prevalence of only 0.24% (3). However, they carry greater risk of adverse outcomes (Table 2). Our case reminds us to always think broadly even with common diagnosis such as hypertension. Additionally, it highlights that more patients with hypertension should be screened for primary aldosteronism.