Case Presentation: An 80-year-old man with prostate cancer and radical prostatectomy with an indwelling Foley catheter presented from his nursing home with three days of hematuria and a hemoglobin of 5.2 mg/dL (baseline 7-9 mg/dL). Initial vital signs were normal. Exam was significant for pink-tinged urine, copious melena, and no abdominal pain. A repeat hemoglobin was 3.8 mg/dL. INR was 1.5 and PTT was 70.5 seconds. Bilirubin, reticulocyte count, and fibrinogen were normal, and no schistocytes were seen on blood smear.Hematology was consulted for the elevated PTT. Workup revealed low factor VIII activity and a mixing study positive for an inhibitor. Factor II, IX, X and XI activities were normal. A Russell’s Viper Venom Test was negative for lupus anticoagulant. The patient was diagnosed with an acquired factor VIII inhibitor, and initial evaluation for hematologic malignancies and autoimmune disorders was negative.The patient was treated with prednisone and factor eight inhibitor bypass activity. The hemoglobin stabilized with red blood cell transfusions. The hematuria and melena resolved. An upper endoscopy and colonoscopy revealed no source of bleeding. Over two weeks, the patient’s PTT decreased to 44 seconds and factor VIII inhibitor titer levels declined. He was discharged with a recommendation for workup for occult malignancy; however, this was not within his goals. Chart review revealed that the mild INR elevation had been present for a year and was attributed to malnutrition. The PTT elevation first manifested five months prior to admission but was never further evaluated despite five admissions or emergency department encounters, including presentations for anemia due to gross hematuria and a spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma. The failure to evaluate this abnormality led to preventable adverse events.

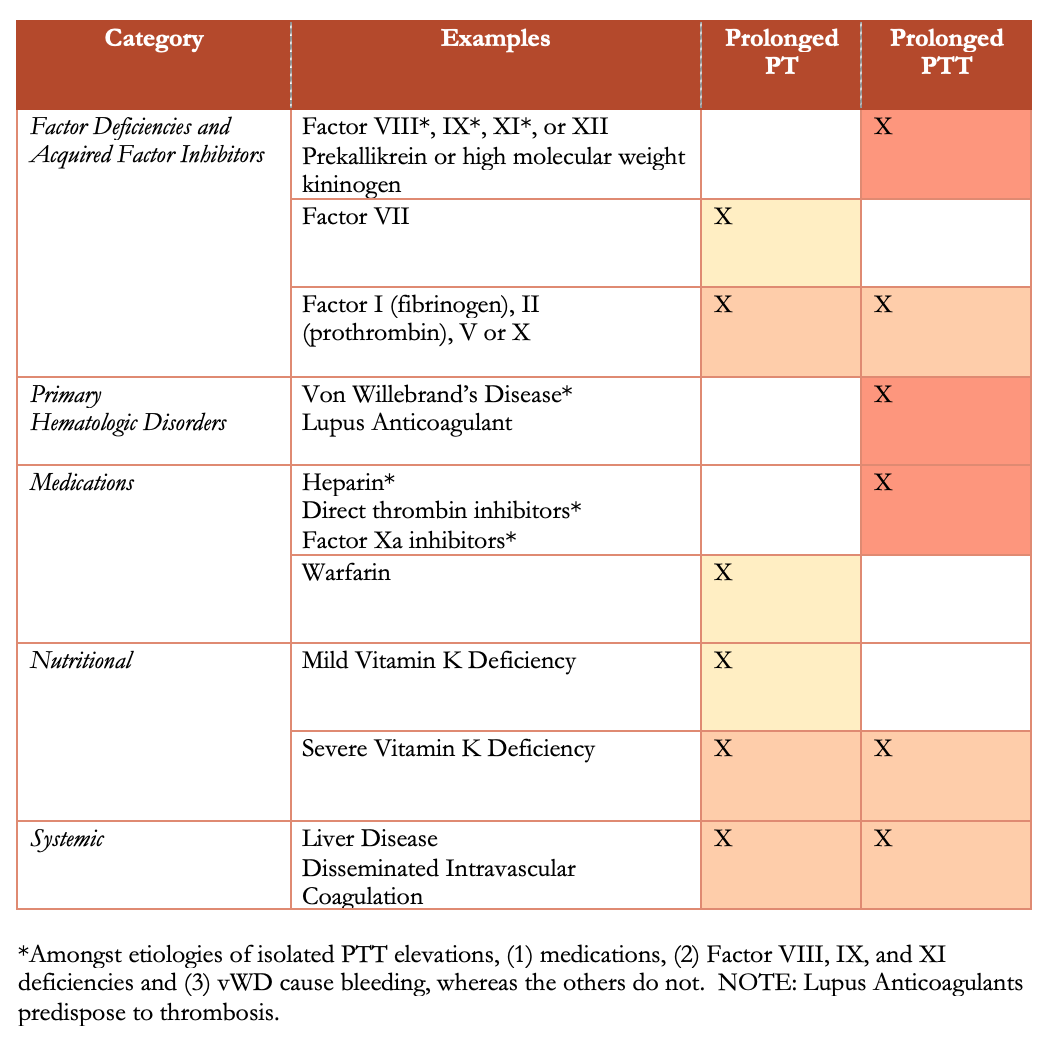

Discussion: Hospitalists frequently encounter uncommon laboratory abnormalities that can be easily overlooked. This patient’s unexplained elevated PTT persisted without evaluation until it manifested as a life-threatening bleeding episode. The failure to assess the elevated PTT was an error, possibly due to lack of knowledge, distraction by other acute medical issues, and attribution bias (i.e. attribution to malnutrition). PT and PTT elevations each have limited differential diagnoses (Table). An isolated PTT elevation poses the most concerning diagnoses, including acquired factor VIII deficiency, acquired von Willebrand disease, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. The first two have serious bleeding consequences, whereas antiphospholipid antibodies are associated with thrombosis. As opposed to PT elevations, which proportionally increase the bleeding risk, PTT elevations can cause bleeding at any level. Treatment with coagulation factors alone is ineffective with an acquired inhibitor. Mainstay therapies include glucocorticoids and factor bypass agents; alternatives include cyclophosphamide and rituximab. In rare cases, inhibitors can spontaneously resolve.

Conclusions: A new isolated or disproportionate PTT elevation without a clear medication culprit represents a potential medical emergency. While lupus anticoagulant is the most common explanation, an acquired factor VIII or von Willebrand inhibitor must be entertained, especially in a patient who presents with bleeding. Catastrophic bleeds can happen at any level of PTT elevation and therefore require immediate diagnostic and therapeutic intervention.