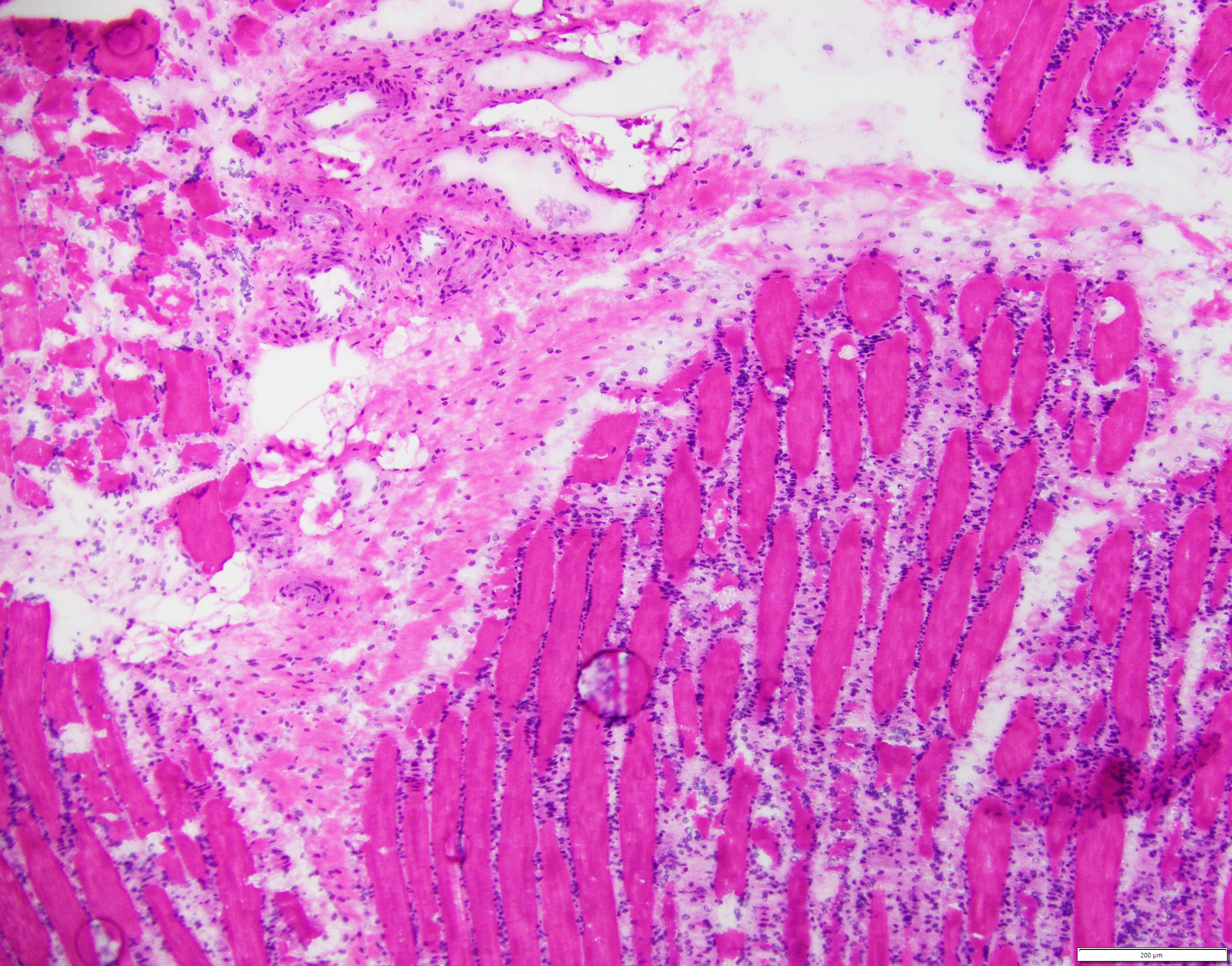

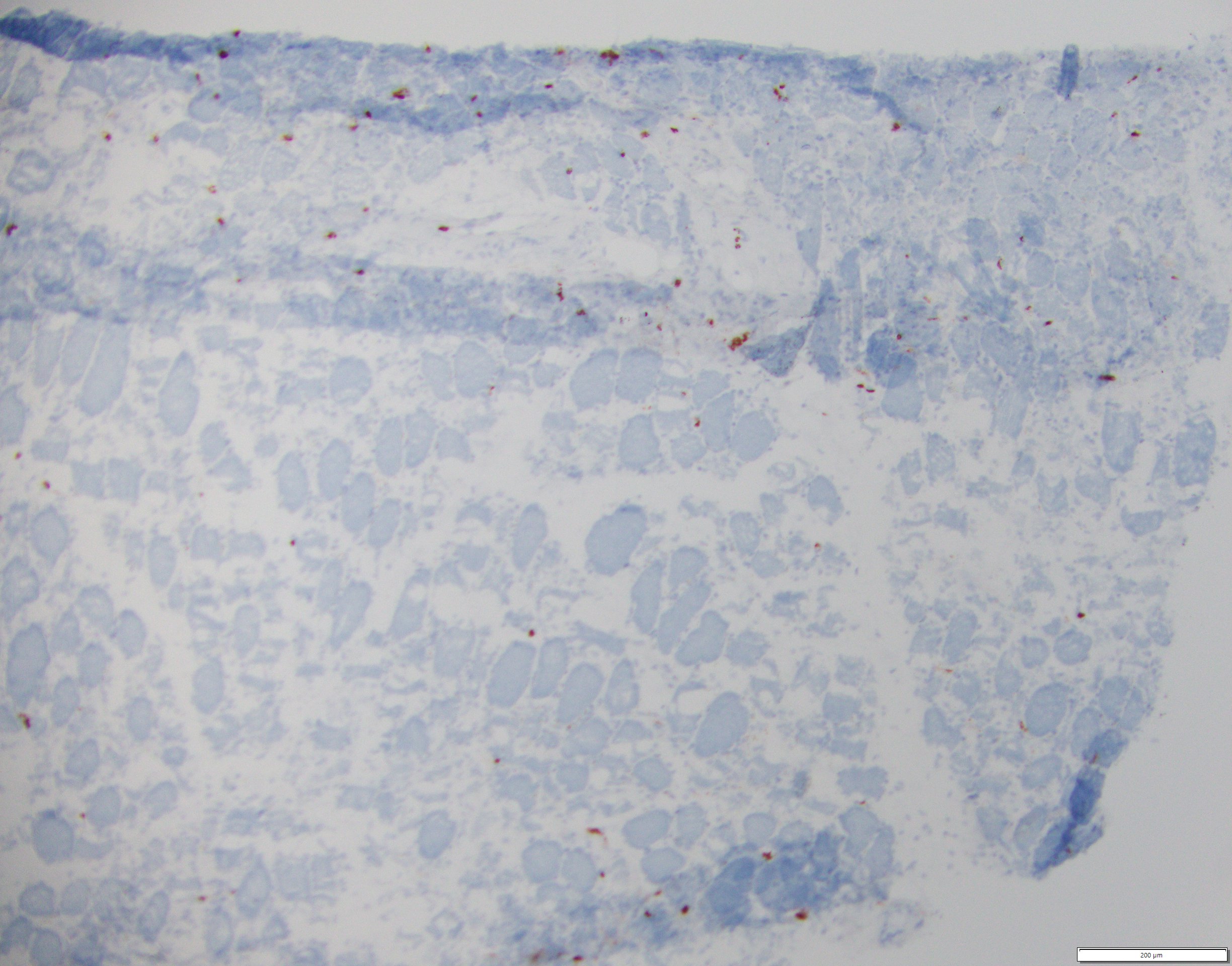

Case Presentation: Lyme disease (LD) is caused by the Ixodes tick-borne infection with spirochetes Borrelia burgdorferi [1]. LD is most commonly reported in the Northeastern and upper Midwestern United States [2]. It is divided into three stages. Early localized, stage 1, with Erythema Migrans (EM) bull’s eye lesion present in 70-80% of patients [1], within 1-2 weeks after a recent tick bite. Early disseminated, stage 2, with multiple EM lesions, facial nerve palsy, lymphocytic meningitis, and heart block within weeks-months [1, 3], and late disseminated, stage 3, with large joint arthritis (i.e. knees), neurologic sequelae (i.e. memory impairment, hypersomnolence, mood disorders), after 6 months [1, 4]. In rare cases, LD can cause myositis. There have been a few reports describing this phenomenon [5-8]. Diagnosing this clinical entity can be challenging, especially if there is low clinical suspicion. We describe in this report a rare case of Lyme Myositis (LM) with an unusual presentation.A 68-year-old male with history of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in remission (treated with an alkylating agent and immunotherapy 4 years ago) presented with proximal muscle weakness and 50 pounds weight loss for six months. He denied any signs of erythema migrans or tick bite. On exam he was cachectic and ill-appearing, small left knee effusion, adequate joints mobility, unable to lift his legs against gravity, mildly upgoing Babinski bilaterally, dry skin throughout. His labs showed normal CPK, minimally elevated Aldolase (10.1 U/L), CRP 12.7 mg/dL. Lyme serology was negative (positive ELISA, negative Western blot), lumbar puncture obtained given his unexplained weakness, CSF fluid showed a typical inflammatory pattern with positive Lyme PCR. Synovial fluid left knee revealed inflammatory joint fluid with positive Lyme PCR, MRI showed bilateral diffuse subcutaneous edema within the pelvic and thigh muscles, fascial edema, suggestive inflammatory myopathy (e.g. myositis), his muscle biopsy showed perifascicular atrophy, widely scattered T-cells, type 1 to type 2 fiber ratio of 1:1, myofiber atrophy involving both fiber types with perifascicular atrophy. And he had severe hypogammaglobulinemia (IgA 14, IgM < 5, IgG 235 mg/dL). Given his CSF findings, IV Ceftriaxone was initiated with the improvement of his joint swelling and muscle weakness, reflected by CRP (decreased from 12.7 to 3.66 mg/dL) without any glucocorticoid or immunosuppressive therapy. He denied any dysphagia or rash. Given his severe hypogammaglobulinemia, also received 40 grams of IVIG.

Discussion: Our case demonstrates complexity diagnosing and treating a patient with LM. Although LD is associated with myalgias, LM is a very rare clinical entity requiring high clinical index in order to obtain the appropriate work-up. Our patient’s negative Lyme test might have due to his severe hypogammaglobulinemia at time of testing, resulting in inability to mount an adequate immune response, despite positive Lyme PCR.

Conclusions: LM is rare manifestation of LD. Often associated with muscle weakness and wasting, diagnosis can be often made with clinical features and serology. If in doubt, biopsy should be considered. LM responses generally well to appropriate antibiotic treatment with improvement of symptoms.