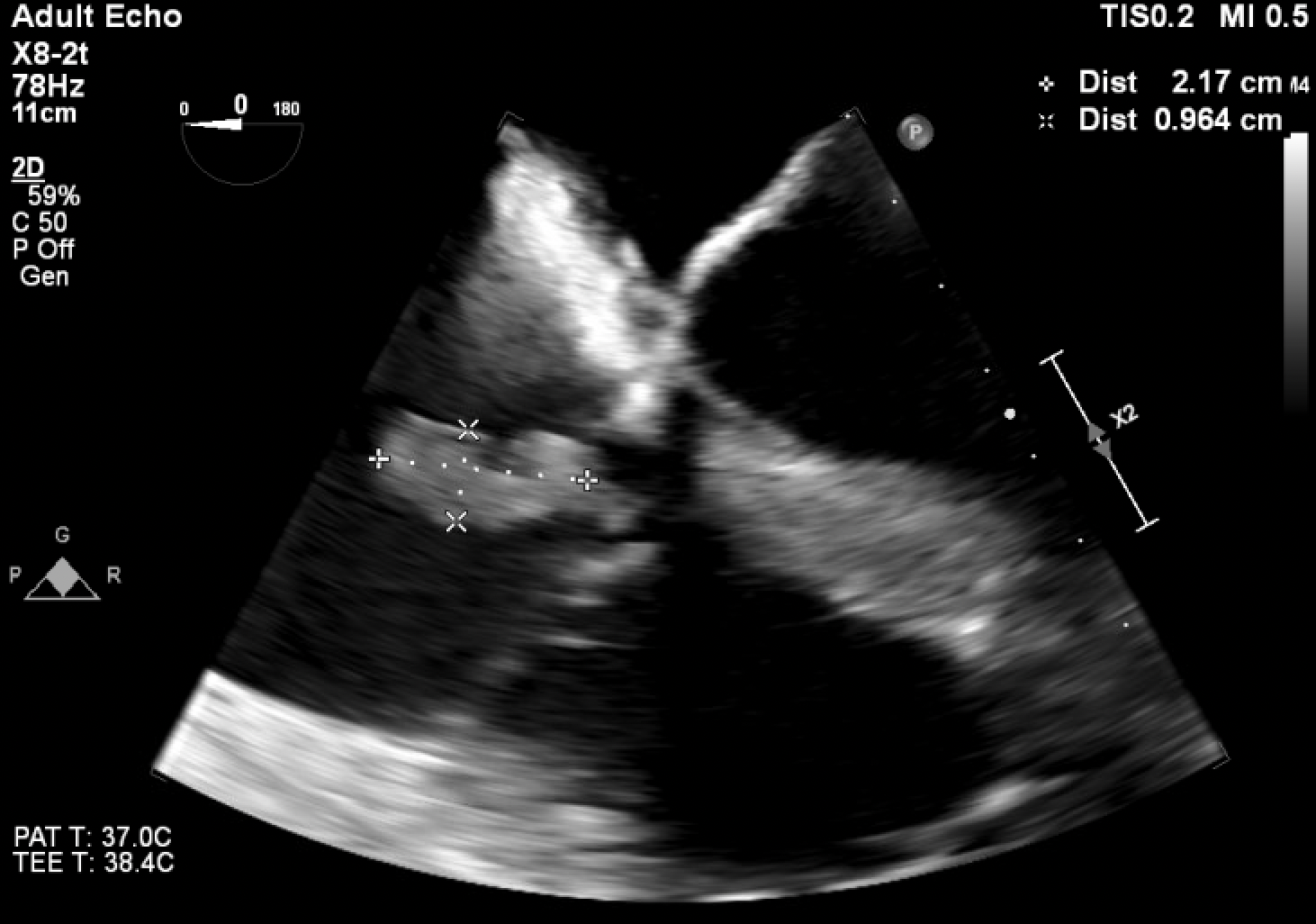

Case Presentation: A 54 year old male with a history of intravenous drug use presented for three days of altered mental status, dyspnea, and low urine output. He was previously admitted a month ago for septic shock secondary to aortic valve endocarditis and underwent aortic valve repair, but left against medical advice before completing his antibiotic course. Upon arrival, he was tachycardic, hypotensive, and tachypneic. The physical exam was notable for a diastolic murmur at the right sternal border and bilateral lower extremity edema with a dark eschar like appearance. He initially improved with broad spectrum antibiotics and fluids, but over the next two days, he rapidly decompensated, requiring two vasopressors to maintain his blood pressure. Concurrently, he developed extensive purpuric lesions and hemorrhagic bullae on his lower and upper extremities. His labs were notable for leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, extensive coagulopathy, significantly low protein C activity of 21%, low to normal protein S activity of 65%, low antithrombin of 40%, and elevated factor VIII activity of 356%. Blood cultures eventually grew methicillin sensitive staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Transthoracic echocardiogram showed new tricuspid vegetation, and the follow up transesophageal echocardiogram confirmed this finding in addition to recurrent aortic vegetation on the prosthetic aortic valve. This constellation of findings was consistent with a diagnosis of septic shock secondary to MSSA endocarditis with purpura fulminans (PF) and acquired protein C deficiency. In the setting of acute PF, other etiologies were considered. Vasopressor necrosis was ruled out, given the timing of the rising vasopressor requirements and the onset of PF. Other infectious etiologies like hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus were all ruled out. Lupus anticoagulant, cryoglobulin, cardiolipin, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, vasculitis panel, and antinuclear antibodies were all negative as well. For treatment, he was continued on triple antibiotic therapy with nafcillin, gentamicin, and rifampin. Protein C treatment was deferred, with his coagulopathy improving on resuscitative measures and antibiotics throughout the admission. Given the severity of his illness and re-infected aortic valve prosthesis, the patient was deemed a poor surgical candidate. The patient eventually decided to pursue hospice care.

Discussion: Clinicians should consider PF in the differential when patients with staphylococcus aureus endocarditis present with cutaneous purpura. Early recognition of PF and treatment with activated protein C may help to limit skin tissue injury. PF is characterized by endothelial damage and a procoagulant state that occurs most commonly as a severe complication of an infection. Therefore, when treating the underlying infection in PF, clinicians should select antibiotics to cover both the more commonly associated endotoxin producing gram negative organisms and gram positive cocci such as MSSA.

Conclusions: This case demonstrates the importance of realizing the association between staphylococcus aureus endocarditis and PF as cases of gram positive endocarditis continue to rise among IV drug users during the ongoing opioid epidemic. After early recognition, starting disease modifying treatment with activated protein C can be vital to the patient outcome.