Background: Published work applying game theory to physician-patient interactions is nearly non-existent [1-4]. The most prominent work is the example of an emergency medicine physician being asked to prescribe opiates for a patient they suspect of opiate use disorder (OUD) seeking opiates for secondary gain (McAdams 2014). McAdams’ game theory analysis suggested that institutional pressure on the physician to avoid poor patient evaluations would encourage inappropriate opiate prescriptions [3,5]. Game theory is a powerful mathematical tool used in the behavioral sciences to better understand and predict the behavior of different parties interacting toward a shared outcome via simplified models. The fundamental principles are that the parties involved are rational (i.e., they predictably seek to achieve their self-benefit), there are known potential actions, and that each party has preferences among the different outcomes. The ‘games’ can be played simultaneously, sequentially, and either once or repetitively. Sequential games can be viewed as a conversation being led by one player and the other reacting. When each party has made their best choice relative to the other parties making their best choices, it is called an equilibrium.

Purpose: An update of McAdams’ game theory-based evaluation of the opiate dilemma with application to hospital medicine will help hospitalists understand their current practice.

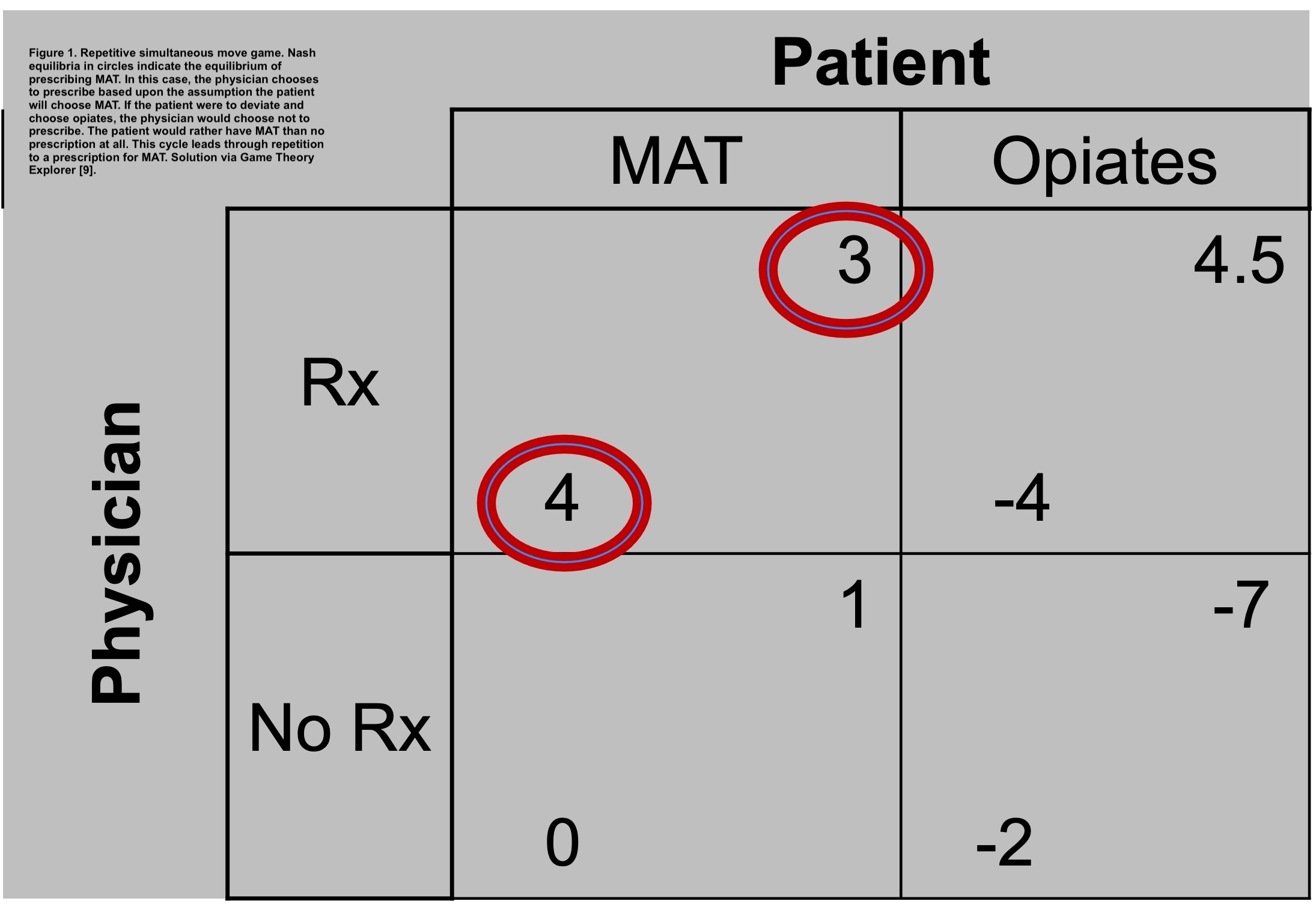

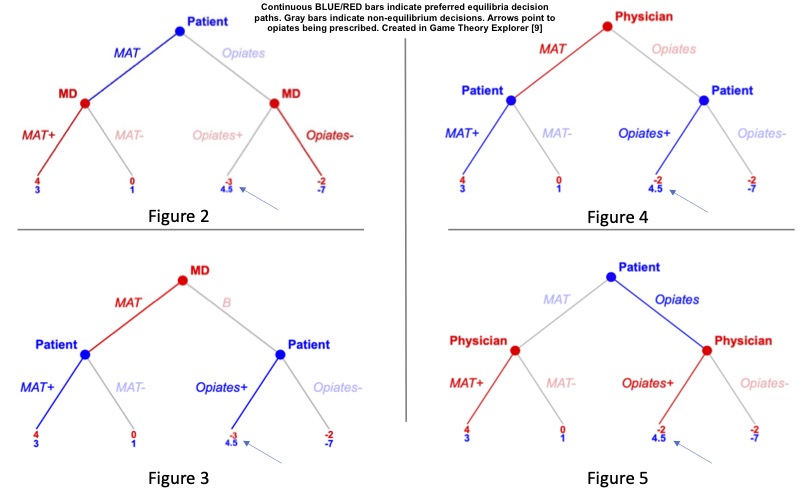

Description: Hospitalists’ perceptions of risk, prescribing practices, total time with patients, and rewards differ from ED physicians. Therefore, the following factors are used to reconsider the prior work. 1. Hospitalists may have greater interests in shifting the patient off opiates due to admitted patients being sicker with diseases related to OUD. 2. Hospitalists see patients repetitively during a visit. 3. Institutions have generally stopped pressuring physicians to prescribe opiates. 4. Buprenorphine is associated with positive outcomes for patients with OUD5. MAT is associated with reduced readmissions [6,7] and discharges against advice [6,8]. These factors are considered in determining payoffs and subsequent equilibria by constructing a classic simultaneous-move 2×2 game table and in the more realistic game of sequential moves. Payoffs are structured to show that physicians prefer MAT>no prescription>opiates and that patients prefer opiates>MAT>no prescription. In both the simultaneous game and the sequential move game, the equilibria (best choice for each) favor using MAT over alternatives. However, if physician preference is MAT> (opiates=no prescription) and patient preference is unchanged, then in sequential move games where patients lead the conversation the physician is likely to give opiates.

Conclusions: Game theory is a valuable tool to evaluate decision-making by patients and physicians. As anticipated, this model shows that with the first set of preferences both patients and physicians will choose MAT. However, this model also demonstrates that if the physician is indifferent between opiates and not prescribing anything (and the patient knows it), then when the patient dominates the conversation, they are more likely to end up with opiates. This implies that if the goal is to decrease inappropriate opiate prescriptions, there needs to be clarity about physician preferences to prescribe MAT>no prescription>opiates or that physicians need to control the conversation.