Background: Hospitalized patients are often kept fasting for various reasons, including clinical conditions, procedures and imaging, or dysphagia (1). Studies have demonstrated the harm of excessive fasting, including increased post-operative delirium (2), thirst and hunger, and patient dissatisfaction. Accordingly, recent guidelines have promoted a more liberal preoperative fasting strategy, namely, allowing clear liquids up to 2 hours prior to elective surgery. Despite the guideline updates, nil per os (NPO) after midnight is still the mainstay of clinical practice for patients receiving elective procedures requiring anesthesia (3, 4). We conducted a quality improvement (QI) project aimed at shortening unnecessary fasting time in hospitalized patients, with a target population of patients waiting for left heart catheterization (LHC).

Methods: The QI project was conducted in a 400-bed tertiary teaching hospital in New York City. Patients on the cardiology teams who had an active NPO order at 7-9AM in expectation of LHC were eligible for the study. The patient demographics, clinical scenario, LHC time, number of missed meals, and NPO hours (including all missed meals and NPO hours up to the time of LHC or when LHC is no longer contemplated) were recorded. Also, a 5-question survey regarding knowledge on fasting requirements and perception of causes for unnecessarily long NPO orders was conducted among the Internal Medicine residents. Educational conferences on diet were designed for the internal medicine residents, jointly prepared by the leaders of this project and the food and nutrition service of the hospital. A second phase of data collection will be conducted after an assimilation period of 2 months to evaluate the effect of the intervention.

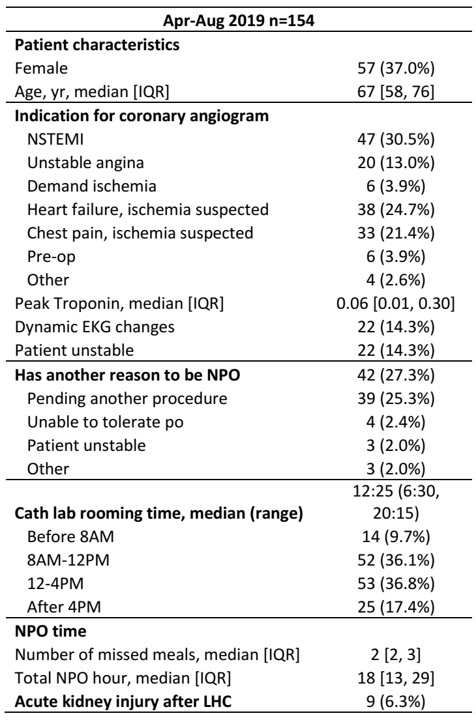

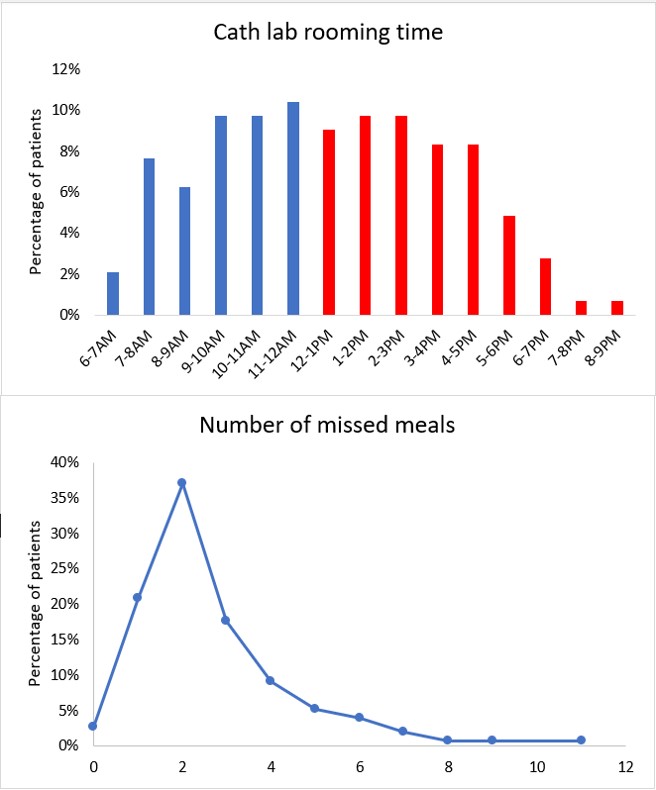

Results: A total of 154 patients were enrolled between 4/2019-8/2019. The median patient age was 67 years old and 57 patients (37.0%) were female. Forty-two patients (27.3%) had a reason other than pending LHC to be fasting. The main indication for LHC was NSTEMI (47 patients, 30.5%), followed by heart failure with suspected ischemia (38, 24.7%), atypical chest pain with risk factors (33, 21.4%), unstable angina (20, 13.0%), demand ischemia (6, 3.9%) and others. The LHC was performed during the hospitalization for 144 patients. The median waiting time between LHC and ED presentation time was 2 days. Patients were taken to the catheterization lab after 12PM in 54.2% of the cases. The median number of missed meals were 2 (interquartile range, IQR [2, 3]) and median NPO hours were 18 (IQR [13, 29]). One hundred residents (32 PGY1, 30 PGY2, 38 PGY3) responded to the questionnaire. Only 36% correctly identified black coffee and 45% soda as clear liquids. When asked what they thought was the cause for excessive NPO orders, 70% chose ‘concern for earlier procedure and possible delays’ and 52% chose ‘it is easy to forget ordering a diet’. Based on the data, we proposed modifications to the institutional practices regarding NPO, including allowing clears until 4AM for patients scheduled for LHC in the morning and allowing a clear-liquid breakfast for patients scheduled for LHC in the afternoon.

Conclusions: Hospitalized patients are often ordered for NPO for prolonged periods of time. There is room for improvement in the residents’ knowledge on the diet and requirement for fasting. This project hopes to promote evidence-based practice and improve patient fasting times prior to procedures.