Case Presentation: Atypical (complement-mediated) Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome is a rare but life threatening thrombotic microangiopathy that affects patients of all ages. About 33-40% of patients sustain end-stage renal disease, stroke, myocardial infarction or have mortality during the first presentation of this syndrome.

We present a case of a 32-year-old previously healthy male who presented to the emergency department with three weeks of abdominal pain and one week of bloody diarrhea. Patient completed a 7-day course of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole without improvement. He also reported dark urine with no significant decrease in urine output. He denied consumption of undercooked meat, recent travels or exposure to sick contacts. Family history was unremarkable for similar symptoms.

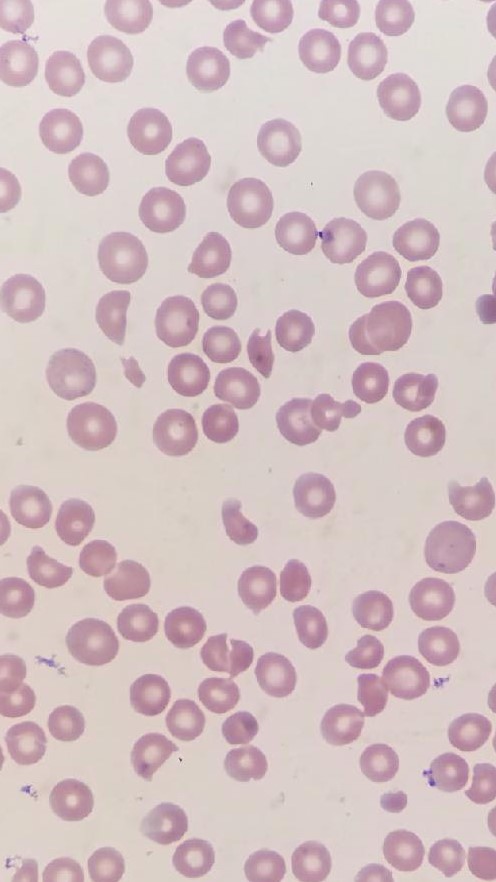

On presentation, patient’s vital signs were stable with physical exam significant for jaundice. No petechiae or purpura were noted, and neurological exam was benign. Fecal occult blood test was positive. Laboratory study revealed hemoglobin of 7.1g/dL, hematocrit 19.7%, platelet 10,000/uL, creatinine 6.16mg/dL, BUN 95mg/dL, AST 81IU/L, total bilirubin 8mg/dL with direct bilirubin 0.7mg/dL. Patient had normal hematologic, hepatic and renal functions two weeks prior. Peripheral blood smear showed moderate schistocytes (See attached image). Lactate dehydrogenase was elevated at 2989 IU/L, INR 1.3, D dimer 3.67ug/ml. Complement Factor H levels were within normal range. Stool studies was negative for E. Coli O157 and Shiga toxin.

Normal Fibrinogen and ADAMTS 13 levels excluded Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia Purpura.

The patient was diagnosed with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. He received multiple red blood cell and platelet transfusions, then underwent two rounds of plasmapheresis. He was given one dose of eculizumab and started to recover steadily. Hematologic derangements and renal function essentially normalized after two weeks.

Discussion: Atypical HUS involves uncontrolled activation of the alternative complement pathway and resulting formation of the membrane attack complex. This disease involves inherited or acquired mutations of gene regulating the complement pathway, however, normal plasma levels of C3, C4, complement factor B, H, and I do not exclude the diagnosis. First line therapy is Eculizumab, an anti-C5 monoclonal antibody which prevents the formation of membrane attack complexes and subsequent thrombotic microangiopathy.

Conclusions: Atypical HUS has more severe morbidity and mortality than shiga toxin medicated HUS. Clinicians should be aware that atypical HUS may be seen in as many as 50% of non-Shiga toxin associated cases of HUS. Plasmapheresis or plasma infusion may temporarily halt disease progression without reversing the underlying pathologic process. Early administration of Eculizumab could ensure a prompt recovery of hematologic and renal function, and therefore improve long term quality of life.