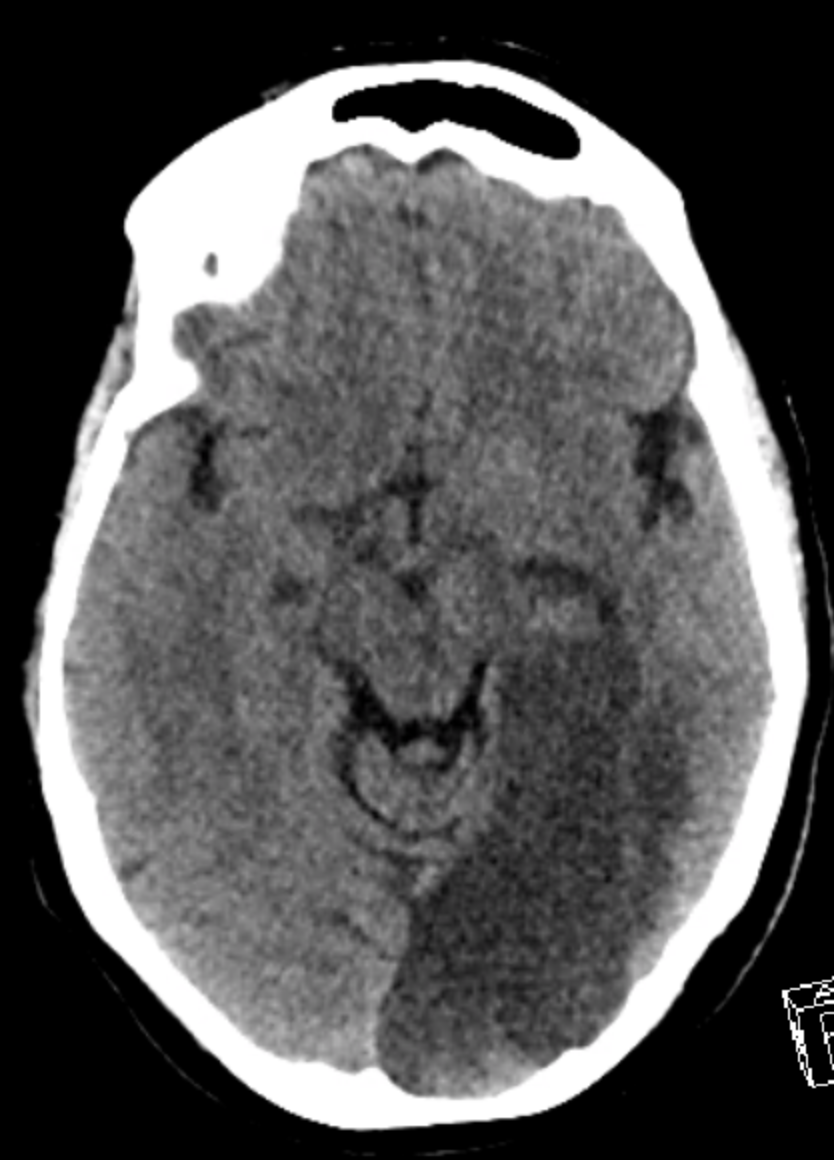

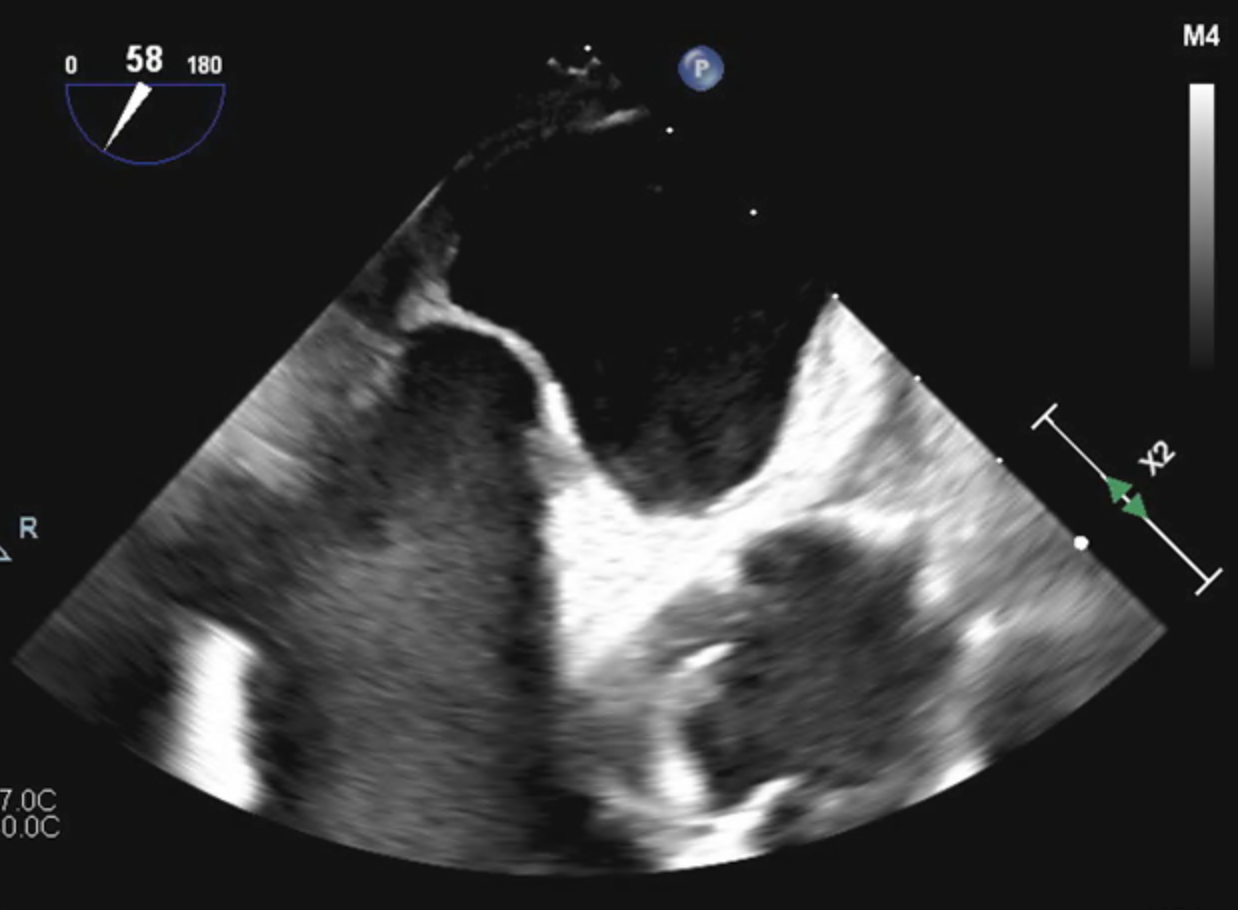

Case Presentation: A 51-year-old female with pseudomyxoma peritonei was admitted to the hospital for surgical debulking. She was started on Lovenox post-operatively. A week later she became hypotensive with acute hypoxic respiratory failure. She was intubated and started on vasopressor therapy with an improvement in her hemodynamics. CT angiogram of the chest depicted a pulmonary embolism (PE) and a heparin drip was initiated. Lower extremity ultrasound revealed a right femoral deep venous thrombosis (DVT). A screening head CT performed in anticipation of tPA administration showed an acute left occipital PCA infarct. Due to relatively stable hemodynamics on low-moderate doses of norepinephrine and the high risk of hemorrhagic transformation, tPA was not administered.Transesophageal echocardiogram with bubble study demonstrated right ventricular strain and a large patent foramen ovale (PFO) with right to left shunt. Neurology was consulted and recommended titrating heparin to a Xa level of 0.5 units to balance the risk of recurrent stroke with hemorrhagic transformation. Unfortunately, despite therapeutic heparin therapy the patient continued to clot and embolize, developing a new right parietal stroke, right internal jugular DVT, and left lower extremity DVT. An inferior vena cava filter was placed to prevent recurrent large PE, and despite the risk of hemorrhagic transformation heparin was titrated to Xa levels of 0.7 units. After this change, there were no new thromboembolic events. The patient was eventually extubated and discharged from the ICU with cardiology follow up for consideration of PFO closure.

Discussion: The role of PFO in cryptogenic stroke in the average patient is conflicting. While some studies have reported PFO to be an independent risk factor for stroke, others have not found this to be the case.1,2 However, the association between PFO and ischemic stroke is stronger when PE is present; one small study showed that up to one in two patients with PE and PFO with large shunt suffered a stroke.3 Balancing the risks and benefits of high-intensity anticoagulation when PE and stroke coexist represents a true challenge. High-intensity heparin is the standard of care for submassive or massive PE, but it introduces the risk of hemorrhagic transformation. For this reason, in cardioembolic stroke due to atrial fibrillation, therapeutic anticoagulation is generally avoided in the first two weeks after a large ischemic stroke. However, data in patients with active DVT, PE, and paradoxical emboli through a PFO are lacking. Given that our patient had a new stroke and clot formation while on moderate-intensity heparin, we deemed it necessary to transition to high-intensity heparin titrated to Xa levels of 0.7 units. Fortunately, the patient experienced no adverse side effects. Preventing further paradoxical embolic events is also an important consideration. For long term stroke prevention in young patients, percutaneous PFO closure leads to a 60% reduction in recurrent stroke.4 In our patient, this risk reduction may be even greater given her underlying hypercoagulable state and large right to left shunt.

Conclusions: Patients with PFO who develop a PE are at an increased risk for paradoxical emboli and stroke. In patients with acute stroke at high risk for further embolic events, high-intensity anticoagulation may be necessary despite the risk of hemorrhagic transformation.