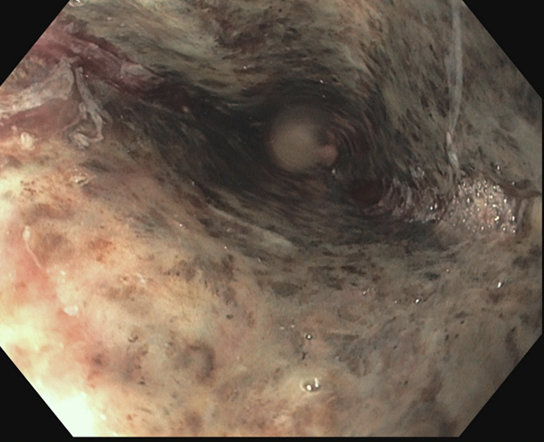

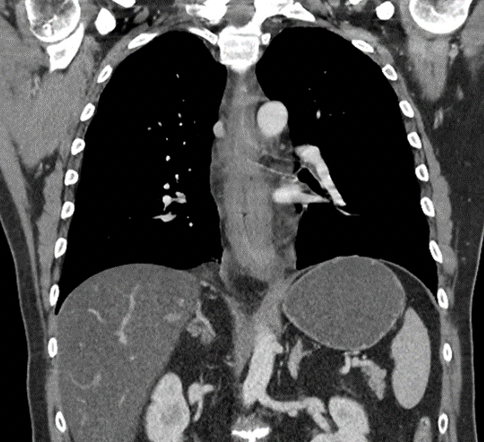

Case Presentation: A 60-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a one day history of emesis, dysphagia, and odynophagia. He endorsed pain in the middle thoracic esophageal region which was worse with swallowing. Initially, his emesis was non-bloody, then subsequent episodes resulted in small amounts of bright red blood. Past medical history was pertinent for alcohol use that increased over the past year to approximately 6-8 vodka drinks per day. He was afebrile, tachycardic to 135, and mildly hypertensive. On exam, he had mild epigastric tenderness and was spitting oral secretions into an emesis bag due to pain with swallowing his secretions. Labs were notable for elevated hemoglobin 18.7 g/dL, elevated hematocrit 52%, elevated white blood cell count of 13.4 per µL, and an elevated anion gap of 40 mEq/L with a bicarbonate of 15 mmolEq/L. Beta hydroxybutyrate was increased at 4.4 mmol/L and urine ketones were markedly positive at greater than 160 mg/dL. In addition, lactate was 5.3 mmol/L. CT imaging of the chest revealed severe edematous changes throughout the esophagus but no without evidence of perforation. Additionally, there was evidence of hepatic steatosis. Upper endoscopy revealed diffuse esophagitis throughout the entire esophagus with a dusky “black” appearance to the distal esophagus. Biopsies were taken confirming the diagnosis of acute esophageal necrosis. The patient was managed with intravenous fluid resuscitation, electrolyte repletion and a proton pump inhibitor. Symptoms gradually improved and his oral diet was advanced over the course of three days.

Discussion: Black esophagus, formally known as acute esophageal necrosis, is thought to be caused by combined ischemic injury and direct mucosal injury resulting from gastroesophageal reflux or other insults. [1] This patient likely suffered hypoperfusion secondary to volume depletion from alcohol consumption and vomiting and direct mucosal injury from gastric contents and severe alcoholic ketoacidosis. The distal esophagus appears to be affected most often, possibly due to less robust blood supply and increased gastric acid exposure. Diabetic ketoacidosis has been previously identified as a risk factor suggesting the metabolic state of ketoacidosis might play a key role in the pathogenesis. [1] The treatment is supportive care with fluid resuscitation, proton pump inhibitors, and management of underlying conditions. Complications include esophageal perforation and stricture. The mortality rates may exceed 30% but are typically secondary to serious comorbid conditions. [2]

Conclusions: Black esophagus, formally known as acute esophageal necrosis, is a rare phenomena that is thought to be caused by combined ischemic injury and direct mucosal injury resulting from gastroesophageal reflux or other insults. [1] The treatment is supportive care with fluid resuscitation, proton pump inhibitors, and management of underlying conditions. Mortality rates her low inpatients 10 to improve with supportive care.