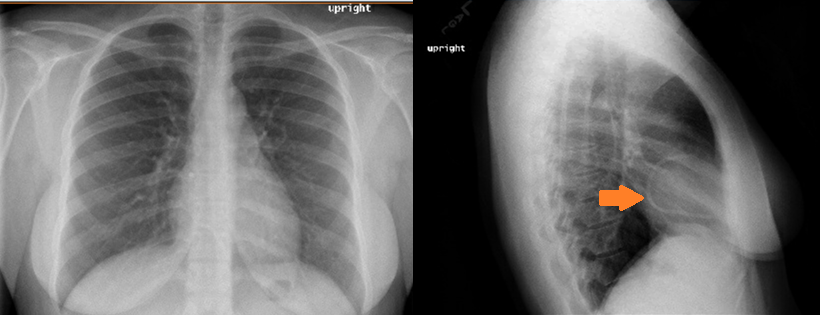

Case Presentation: A 29 year old female with past medical history significant for hyperemesis gravidarum requiring total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with chest pain. She had been having intermittent chest pain for the last 3-4 years, which she had always attributed to the scar from her infusion port. An infusion catheter was placed during her pregnancy 4 years earlier for TPN, which was subsequently removed after delivery. She described the chest pain as a dull pressure, which felt like “food getting stuck” and was located behind her sternum without radiation. She noted that the pain was worse after eating food and increased with exertion. The pain lasted for less than an hour and did not change with medications. She denied fevers, chills, chest trauma, syncope, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, vomiting or diarrhea. Her last menstrual period was 3 weeks prior. She was seen by her primary care provider for increased chest discomfort and was sent to the ED for evaluation. In the ED, she was found to have normal vital signs. Her electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with a rate of 68 without ST elevations or T wave inversions. Her hemoglobin was at baseline of 12.6, white blood cells were 7.4 and basic metabolic panel was unremarkable. Chest radiography was performed which demonstrated a section of 12 cm long tubing curved within the right atrioventricular region concerning for a retained Permacath. The patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital and had the 12cm catheter removed by interventional radiology using a snare. She subsequently reported resolution of her intermittent exertional chest pain and was discharged the following day.

Discussion: In the United States, about 5 million central line catheters are placed for intravenous access annually. Yet the known number of complications not related to infections, such as device failure, remains limited. According to a few published studies, the rate of central venous catheter fractures ranged from 2.5-4.3%. Additionally, guidelines regarding the procedures for catheter removal are less strictly regulated than that of catheter insertion. The risks associated with inappropriate catheter removal can be serious and include bleeding, air embolism, catheter fragmentation, pulmonary embolism, stroke and death. We believe identifying catheter failure can routinely be done during the process of removing catheters. This step can be performed by knowing the length of the catheter at insertion and measuring the catheter length after removal. Additional care taken during the catheter removal procedure can minimize later serious complications from both the removal process and catheter related failures.

Conclusions: To prevent catheter associated injuries we urge for the proper training during both insertion and removal of any central line catheters. During insertion, care should be taken to avoid inadvertent catheter damage, usually resulting from inappropriate angle of insertion or forceful needle/ wire manipulation. Additionally, a frequently overlooked aspect of catheter placement is the removal procedure. We recommend that all practitioners who will be removing central lines be trained in proper catheter removal techniques, which include positioning (Trendeleberg position for internal jugular catheters), allowing for enough time for hemostasis after removing the catheter, using sterile occlusive dressing over the insertion site, and routinely performing visual inspect all catheters to ensure complete removal.