Background: Healthcare provider burnout includes emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished sense of personal accomplishment. No recent study assesses burnout among academic hospital medicine (HM) physicians. A 2011 study of hospitalists at 20 academic medical centers noted burnout near 25%. Few studies assess burnout among Advanced Practice Providers (APPs) which include Physician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners, with APP burnout estimates around 30%. No studies assess burnout among Clinical Assistant (CA) staff who assist hospitalists with obtaining patient medical records and scheduling discharge follow-up. Burnout is associated with healthcare provider demographics, job characteristics, and burnout drivers. The purpose of this study is to assess prevalence and associations of burnout and job satisfaction among academic HM physicians, APPs and CAs in one division.

Methods: We distributed an online, anonymous survey September – November 2020 to 118 physicians, 25 APPs, and 6 CAs (n=149) at one academic HM division in the Midwest. Surveys used the Mini-Z to assess burnout, job satisfaction, stress, workload, time for documentation, work environment, leadership, and related demographic and provider characteristics. We assessed parenting responsibilities, job retention, and work-life balance. We used complete case analysis to determine prevalence of burnout, job satisfaction, and related factors. We used bivariate and multivariate linear regression to determine burnout and job satisfaction associations with related measures. The study received institutional review board approval.

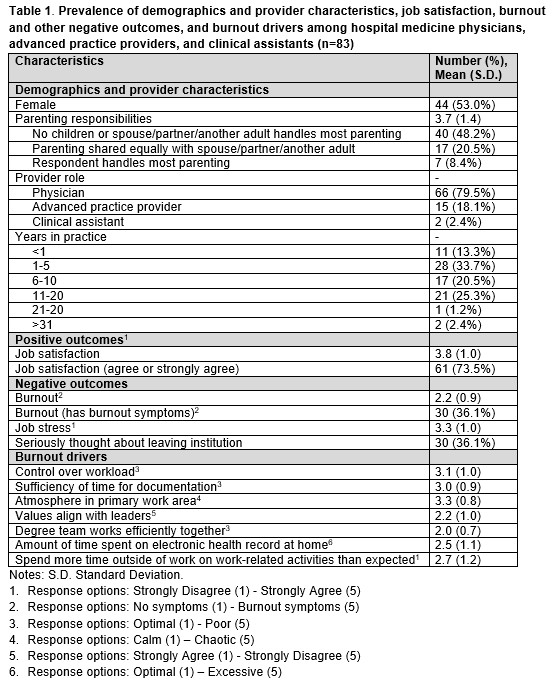

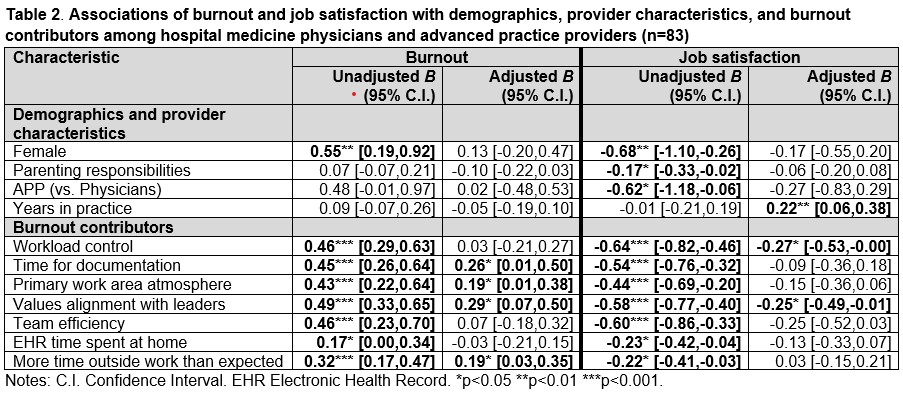

Results: We received 95/149 (64%) partial surveys, of which 83/149 (56%) contained complete responses from66 (80%) physicians, 15 (18%) APPs, 2 (2%) CAs, 44 (53%) female, and 28 (34%) 1-5 years in practice. Among these complete responses, 61 (74%) were satisfied with their job. However, 30 (36%) had symptoms of burnout, and 30 (36%) seriously thought about leaving the institution. See Table 1 for prevalence of burnout contributors. See Table 2 for bivariate linear regression analyses for burnout and job satisfaction. Multivariate linear regression analyses in Table 2 showed burnout was associated with insufficient time for documentation (B 0.26, 95% CI 0.01-0.50), chaotic work atmosphere (B 0.19, 95% CI 0.01-0.38), values misalignment with leaders (B 0.29, 95% CI 0.07-0.50), and more time outside work than expected (B 0.19, 95% CI 0.03-0.35); job satisfaction was associated with increased years in practice (B 0.22, 95% CI 0.06-0.38), but negatively associated with poor workload control (B -0.27, 95% CI -0.53, -0.00), and values misalignment with leaders (B -0.25, 95% CI -0.49, -0.01).

Conclusions: Burnout is present in more than 1 in 3 physicians, APPs and CAs among one academic HM division. This burnout prevalence is higher than determined a decade ago among peer academic medical centers, but this study’s prevalence may have been affected by COVID-19 patient care burden or survey response rate <65%. Despite this burnout prevalence, nearly 3 in 4 physicians, APPs and CAs are satisfied with their job among one academic HM division. HM leadership can consider assessing burnout and job satisfaction and addressing burnout contributors.