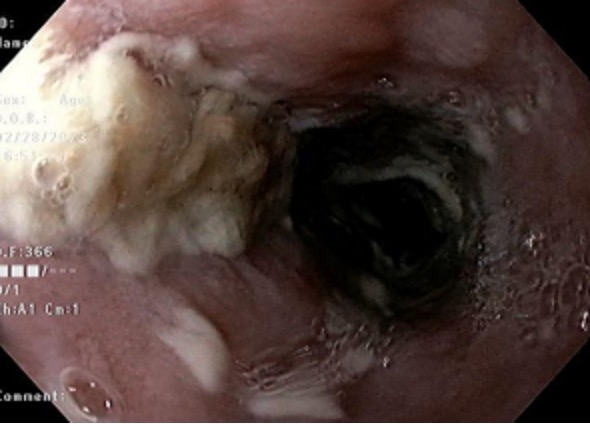

Case Presentation: The patient is a 50-year-old male with a past medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heavy alcohol use, and one pack per day tobacco use who presented with epigastric abdominal pain, an episode of hematemesis, and a three-week history of nosebleeds and bloody sputum. After admission, the patient described the pain as dull and reported radiation of the pain to his chest without painful swallowing. Diagnostic evaluation included a negative chest X-ray, EKG with normal sinus rhythm, and negative high-sensitivity troponin. He was hemodynamically stable, and labs revealed a normal hemoglobin and a HgbA1c of 6.7. Due to his hematemesis, he was initially started on ceftriaxone, octreotide, and omeprazole. Right upper quadrant ultrasound showed mild hepatomegaly with heterogenous hepatic echotexture and trace right upper quadrant ascites. EGD showed diffuse esophageal candidiasis with no active bleeding. Prompt HIV antigen testing was negative and confirmed with negative antibody testing along with a negative hepatitis panel. The patient was started on a two-week course of oral fluconazole and discharged home in stable condition.

Discussion: Esophageal candidiasis (EC) is considered an opportunistic infection found in immunocompromised hosts, commonly those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Almost 10-15% of HIV patients are likely to develop EC. It is much less likely for an immunocompetent individual to be diagnosed with esophageal candidiasis especially without the hallmark symptom of odynophagia as it only affects about 0.32-5.2% of the general population. One potential risk factor for this patient, as documented in other studies, is diabetes mellitus. However, this patient’s diabetes was well-controlled, and he was without any other systemic manifestations of diabetes. Additionally, while proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use is a risk factor for developing esophageal candidiasis, the patient’s candidiasis was identified on EGD just two days after initiating PPI therapy, which was unlikely enough time to develop fulminant esophageal candidiasis but could have worsened the disease process. The final, and most likely, potential nidus for the patient’s candidiasis could be related to his extensive alcohol and tobacco use history. Alcohol and tobacco are both known to be risk factors for esophageal candidiasis due to a variety of mechanisms including direct mucosal irritation and damage.

Conclusions: Although esophageal candidiasis is typically thought of as an infection affecting immunocompromised hosts, particularly as an AIDS-defining illness, it is also important to remember that it can affect fully immunocompetent individuals. Prompt referral for diagnostic evaluation can prevent iatrogenic exacerbation of the disease as empiric treatment for similar symptoms with PPIs can worsen the infection. Therefore, it is paramount for clinicians to remember that esophageal candidiasis should also be considered in at-risk, immunocompetent patients.