Background: Skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) is a common pediatric diagnosis with substantial economic cost. SSTIs vary in severity and clinical presentation. Providers often fear missing serious systemic infection, causing potential overtesting. However, recent studies suggest that blood cultures (BCx) are not useful in management of simple cellulitis or abscess (uncomplicated SSTIs [uSSTI]), and complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) are of questionable value. Unfortunately, there are no nationally approved uSSTI diagnostic practice guidelines to address testing overuse. We identified high variability in uSSTI testing at our institution and aimed to reduce test overuse at our large urban pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) service. SMART AIM: In 3 months, ↓ number of total and mean/patient tests (BCx, CBC, ESR, and CRP) by 25% for uSSTI patients admitted to the PHM service.

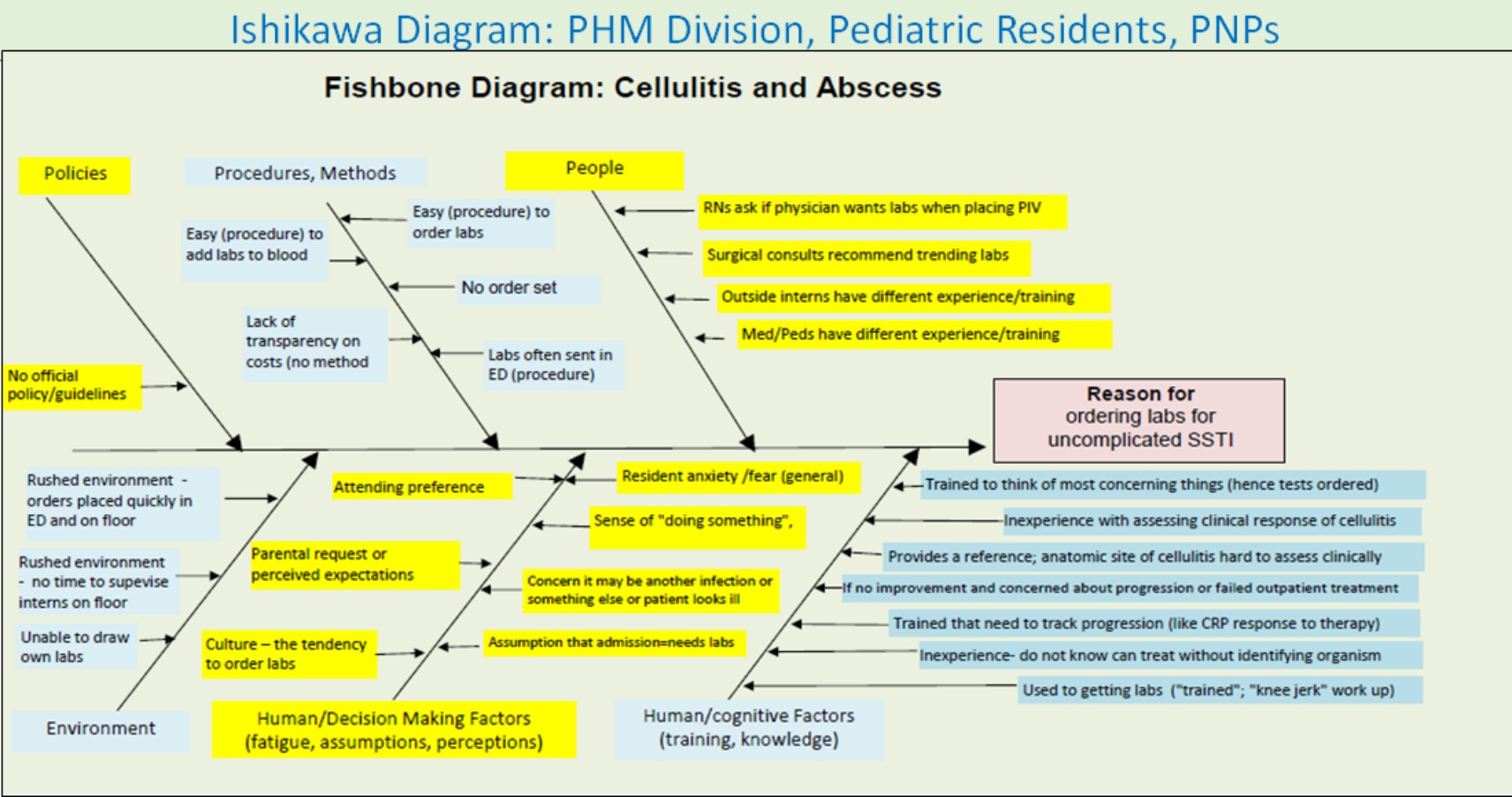

Methods: Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (C): P: Interdisciplinary team of physicians (PHM, ID), nurses, lab, pharmacy, residents, quality management, and IT created; evidence-based medicine literature, baseline data reviewed. Ishikawa diagrams completed by key stakeholders identified drivers for testing (Fig 1). Interventions chosen to address process (pathway order set created) and culture (fears, habits addressed with education). D: C1: Clinicians educated and uSSTI order set implemented; C2: order set auto-populated to residents’ “favorites” SA: Data reviewed with team monthly; PHM- and resident-specific feedback given.

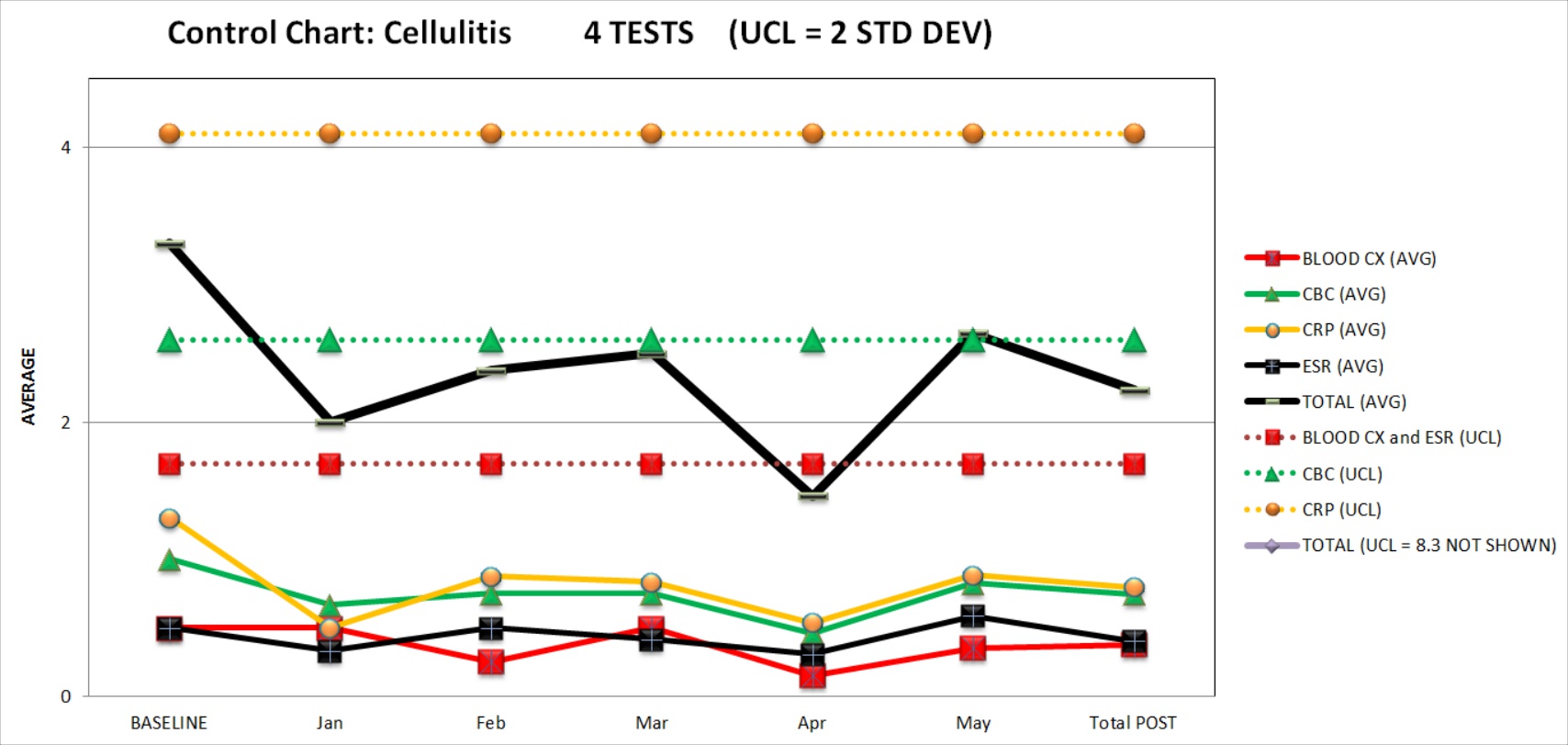

Results: Baseline year (2016): Total 573 tests; mean 3.3 tests/patient. Post-implementation: 89% (50/56) of eligible patients on pathway. Total tests ↓ to 56; mean tests/patient ↓ to 2.2 (40% ↓ (Fig 2)). There were no adverse outcomes or unplanned re-admissions. Projected 2017 savings from reduced use of these 4 tests are $55,989 using normalized 5-month post-intervention data.

Conclusions: Our interdisciplinary team exceeded our aim of reducing unnecessary testing in patients with uSSTI with no patient harm and with real cost savings. Awareness of local culture, creation of a pathway defining appropriate patient selection, interdisciplinary teamwork, and clinician feedback can help change behavior and are important when initiating new “Choosing Wisely”-style interventions. The close relationship between ED and PHM may have positively influenced ED ordering practices. Next steps include creation of a formal ED-PHM QI collaborative to further reduce unnecessary testing and to address antibiotic stewardship and photo use.