Background: Inpatient admissions for Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) represent a substantial economic burden within the US healthcare system with patients experiencing high rates of 30-day readmission and mortality. To more efficiently and effectively serve complex cardiovascular (CV) patients at a major cardiac care center, Intermountain Health created a dedicated CV hospitalist service which has expanded from 1 FTE in 2005 to 18 FTE across 2 hospital campuses in 2023. We report 4-years of outcomes from dedicated CV hospitalist vs traditional hospitalist care in terms of combined all-cause 30-day readmission and mortality.

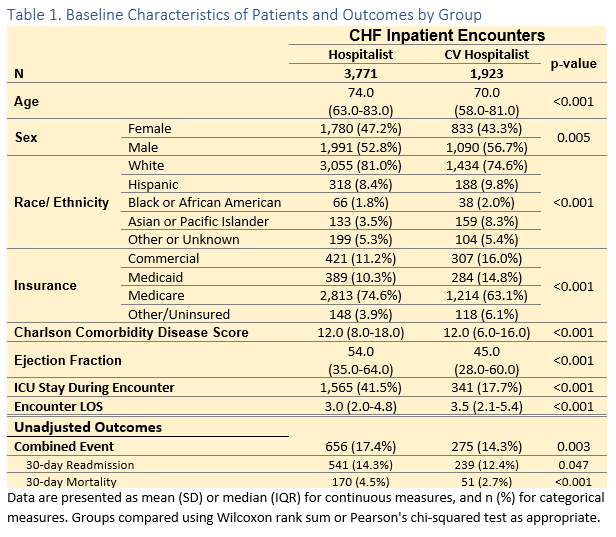

Methods: This retrospective cohort study from Dec 2018 – Dec 2022 reports inpatient admissions with a primary diagnostic ICD-10 code for CHF within 12 Intermountain Health hospitals, a large not-for-profit in the Intermountain West. Encounters were excluded if they left Against Medical Advice (AMA), discharged on hospice, died inpatient, or if admitted as intrahospital transfers as care at outside facilities could not be reviewed in depth. Encounters were defined as CV hospitalist if discharged from a CV hospitalist primary team and hospitalist if discharged by a traditional hospitalist primary team. Only index hospitalizations were included (defined as no inpatient admission within prior 90-days by patient ID) to account for multiple related readmissions. ICUs are closed (staffed by fellowship trained intensivist) for CV hospitalist patients and often open or include stepdown units (staffed by hospitalists) for hospitalist patients. The primary outcome of combined 30-day all-cause readmission or mortality and secondary outcomes of 30-day readmission and mortality are reported independently. Death was identified by state death database review to ascertain any death occurring outside our system. All outcomes were assessed by logistic regression. Descriptive characteristics (used as covariates in models) and unadjusted outcomes are reported in Table 1. First ejection fraction (EF) during the inpatient admission was accepted and, if missing, the nearest EF +/- 3 months of the encounter was used. EF remained missing in 346 (6%) encounters and was imputed by K-nearest neighbor with all other primary model predictors. Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome were modeled by mixed effects logistic regression (accounting for providers, hospitals, and repeat patient encounters) and propensity matching.

Results: Our cohort included 5,694 CHF inpatient encounters from 12 rural, community, and academic hospitals. CHF patients cared for by the CV hospitalists vs traditional hospitalists were younger (Median 70 vs 74 YO) , equally comorbid (Median Charlson Comorbidity Disease Score 12 vs 12), had lower EF (Median 45% vs 54%), less ICU utilization (18% vs 42%), and longer encounter LOS (Median 3.5 vs 3.0 days). CV hospitalist patients experienced better primary and secondary outcomes (Table 1). After adjustment, CV hospitalists have a significant 17% reduction in the OR of combined primary outcome (OR 0.833, CI 0.670-0.997, p=0.029) (Table 2). Mixed effect (OR 0.823, p=0.034) and propensity matching (0.755, p=0.002) models confirm the direction, magnitude, and significance of the observed effect of CV hospitalists on the primary outcome.

Conclusions: We report that, despite caring for more advanced CHF, the use of a dedicated and mature CV hospitalist program is associated with favorable outcomes in combined 30-day readmission and/or mortality.