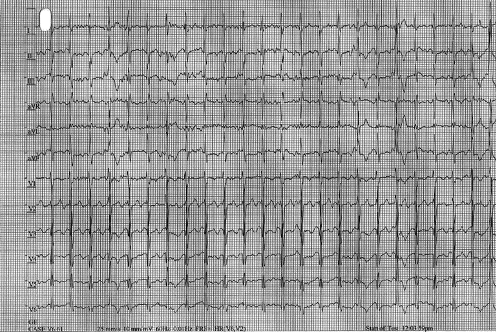

Case Presentation: Case 1: A 14-year-old male presented to the ED with history of a convulsive syncopal episode (third lifetime event). All syncopal episodes occurred with exertion and required cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Episodes were initially considered to be due to a seizure disorder and were treated with antiepileptic therapy (Keppra). Given event recurrence despite escalating doses of Keppra, alternate etiologies were explored. Cardiac evaluation was pursued, which included an exercise stress test that demonstrated sinus rhythm at baseline and frequent polymorphic premature ventricular contractions during exercise. Subsequently, an electrophysiology (EP) study was performed and spontaneous polymorphic ventricular tachycardia was observed during high-dose isoproterenol infusion. Genetic testing revealed a pathogenic ryanodine receptor mutation confirming a diagnosis of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. He was treated with beta blocker therapy and exercise restriction. Antiepileptic treatment was discontinued and he has not had any subsequent syncopal events.Case 2: A 17-year-old male with recurrent convulsive syncope (CS) thought to be due to epilepsy presented to the ED with non-specific chest pain during a febrile illness. An ECG while febrile revealed right ventricular conduction delay with coved-type ST elevation in lead V1 consistent with a type I Brugada syndrome (BrS) pattern. Epilepsy was originally diagnosed at 14 years given a history of recurrent syncope with fine tremors of the upper extremities. Electroencephalogram (EEG) was normal. Antiepileptic therapy was initiated but syncopal events persisted despite escalating doses. Diagnostic EP study showed no inducible atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, but primary-prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was implanted given his high-risk history and clinical findings. He has not had further syncopal episodes and has not received any ICD shocks. Prompt antipyretic therapy has been recommended. Genetic testing for BrS showed no pathologic mutations, but yield of testing is known to be 15-30% in patients with a clinical BrS phenotype.

Discussion: Clinical manifestations of inheritable cardiac channelopathy disorders can include CS, which can lead to a presumed diagnosis of epilepsy. CS is caused by abrupt cerebral hypoperfusion of various etiologies, resulting in loss of consciousness with extensor stiffening and non-sustained myoclonus. In the case of cardiac channelopathies, CS occurs as a result of malignant ventricular arrhythmias (polymorphic VT) with resultant abrupt cerebral hypoperfusion. Non-sustained events can have full recovery but sustained events can be fatal.

Conclusions: Misdiagnosis of CS as epilepsy can occur and other non-neurologic etiologies should be explored particularly if antiepileptic treatment fails. Patients should have their clinical events carefully assessed for potential triggers or circumstances, such as fevers and exercise. A detailed family history should be assessed with attention to first-degree relatives with history of sudden cardiac death. Those with suspicious findings should be referred for cardiac evaluation, which may include exercise testing and diagnostic EP study.