Background: Digital bedside information displays can alert clinicians about patient safety hazards, but the unintended consequences of these interventions are not well understood. Introducing new digital interventions may have implications for clinician satisfaction with the electronic environment, clinical team communication, and patient-centered care. Toward greater understanding of these unintended consequences, we described the content, form, and use of signs and screens in hospital rooms. We used this description to inform a future bedside intervention to improve physicians’ known suboptimal awareness of hazards (e.g., catheters and wounds) hidden under the patient’s sheet and gown.

Methods: We systematically photographed and categorized all signs and screens (by purpose, audience, and reading grade level) at the entrance and inside all occupied hospital rooms in a 20-bed medical-surgical step-down unit of a large, academic hospital, daily for 7 days then weekly for 3 weeks.

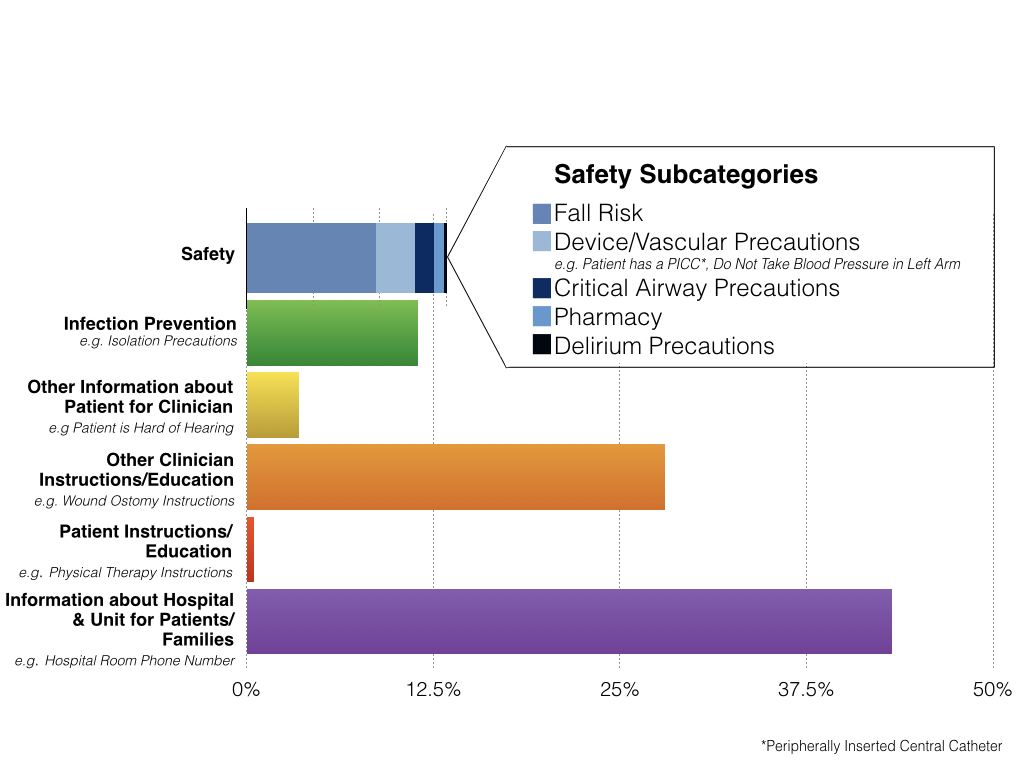

Results: 146 single-bed hospital room surveys were performed over 10 data collection days (mean: 15 rooms/day). 1,707 signs were recorded, with mean of 11.8 signs/room in addition to 2 digital screens (a vital sign monitor continuously displaying heart rate/rhythm, blood pressure, oxygen, temperature, and a clinician work station’s screen available after entering password to access electronic medical records). Signs’ purposes (Figure) included: 1) Safety (Device/Vascular Cautions, Critical Airway, Pharmacy, Fall Risk, Delirium Precautions), 2) Infection Prevention (Isolation Precautions/Hand Hygiene), 3) Other Information about Patient for Clinician (e.g., blind), 4) Other Clinician Instructions/Education, 5) Patient Education, and 6) Hospital & Unit Information for Patients/Visitors. The most common category (43%) was ‘Hospital & Unit Information for Patients/Visitors.’ Signs to improve safety and infection prevention comprised 24% of all signs (Figure), had an average Flesch-Kincaid Reading Grade Level of 6.9 U.S. grade level, and included an average of 51.6 words per sign. Peripherally-inserted central catheters (PICCs) were the only catheter with a reminder sign in the room.

Conclusions: Current use of signs and displays rarely remind clinicians of hazards hidden under sheets (e.g., catheters, wounds) other than paper signs indicating PICC presence. With nearly a dozen signs and 2 digital screens in the average room competing for clinicians’ attention, there is a strong tradition of using in-room signs and displays to communicate with bedside clinicians, although there is a strong potential for this displayed information to distract or be ignored. Developing a new visual tool such as a bedside screen to alert clinicians of hazards present under sheets (e.g., catheters, wounds) may be an opportunity for improving clinician awareness. However, such a display would need to be developed carefully, incorporating human factors to prompt routine attention to the display but not adding to alarm fatigue.