Background: Missed, incorrect, or delayed diagnoses may lead to preventable harm and are common in U.S. hospitals. Until recently, little attention has been placed on mitigating risk attributed to diagnostic error in hospitalized patients. Because system and cognitive factors contribute to these errors, they are also uniquely difficult to systematically address. Many studies have demonstrated that “time-outs,” most commonly applied to surgical settings, can reduce rates of medical error. These instruments could be used to encourage clinicians to acknowledge, confront, and address uncertainty in the diagnostic process in a structured way. As part of our AHRQ-funded Patient Safety Learning Laboratory, we are engaging with clinical stakeholders, systems engineers, and human factors experts to identify key dimensions in the diagnostic process that are prone to failure. We aim to design and develop systematic solutions to address the most common failures.

Purpose: We report our experience designing and developing a structured “diagnostic time-out” as a tool that clinicians can use to identify and address potential diagnostic error.

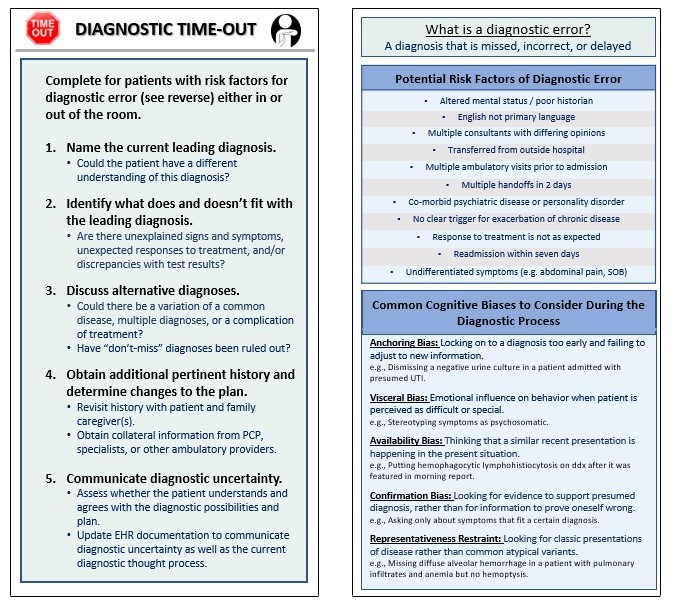

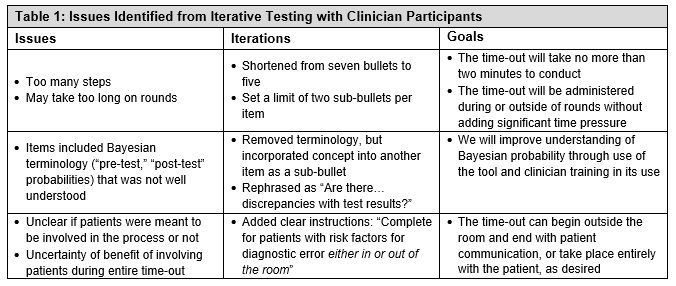

Description: We reviewed the literature and identified five instruments (e.g. Graber Diagnostic Checklist) to inform our tool. We then mapped content from these instruments to address key failures in the diagnostic process. Our goals were to address the most common failures and compile patient risk factors and clinician cognitive biases commonly encountered in the hospital. We presented a draft to key stakeholders and subject matter experts and incorporated their input into a prototype. Over a four-week period, we tested the time-out in eight sessions with eighteen clinician participants caring for general medicine patients. After each session, we used a group consensus approach to address issues from feedback we received (Table 1) in order to rapidly iterate the prototype prior to the next session. Overall, participants perceived that the diagnostic time-out was useful: in three cases in which we simulated its use, it led clinicians to consider additional history, testing, and diagnostic possibilities for their patients with diagnostic uncertainty. The final time-out tool (Figure 1) has five steps, each with one or two sub-bullets.

Conclusions: Clinicians largely supported use of a structured diagnostic time-out for patients with diagnostic uncertainty. However, clinicians voiced concerns about when to initiate the time-out, who would initiate it, the time it would take to complete, and whether clinicians could or should conduct it in the presence of patients. We plan to pilot the diagnostic time-out tool as part of a formal educational curriculum on diagnostic uncertainty for physicians and physician trainees. We are exploring how to leverage our electronic health record to prompt clinicians to take a diagnostic time-out for patients who either are at elevated risk of diagnostic error or report concerns with the diagnostic process via a patient questionnaire. Key challenges will be empowering nurses or others health professionals to initiate the time-out, as well as conducting time-outs in the patient’s room.