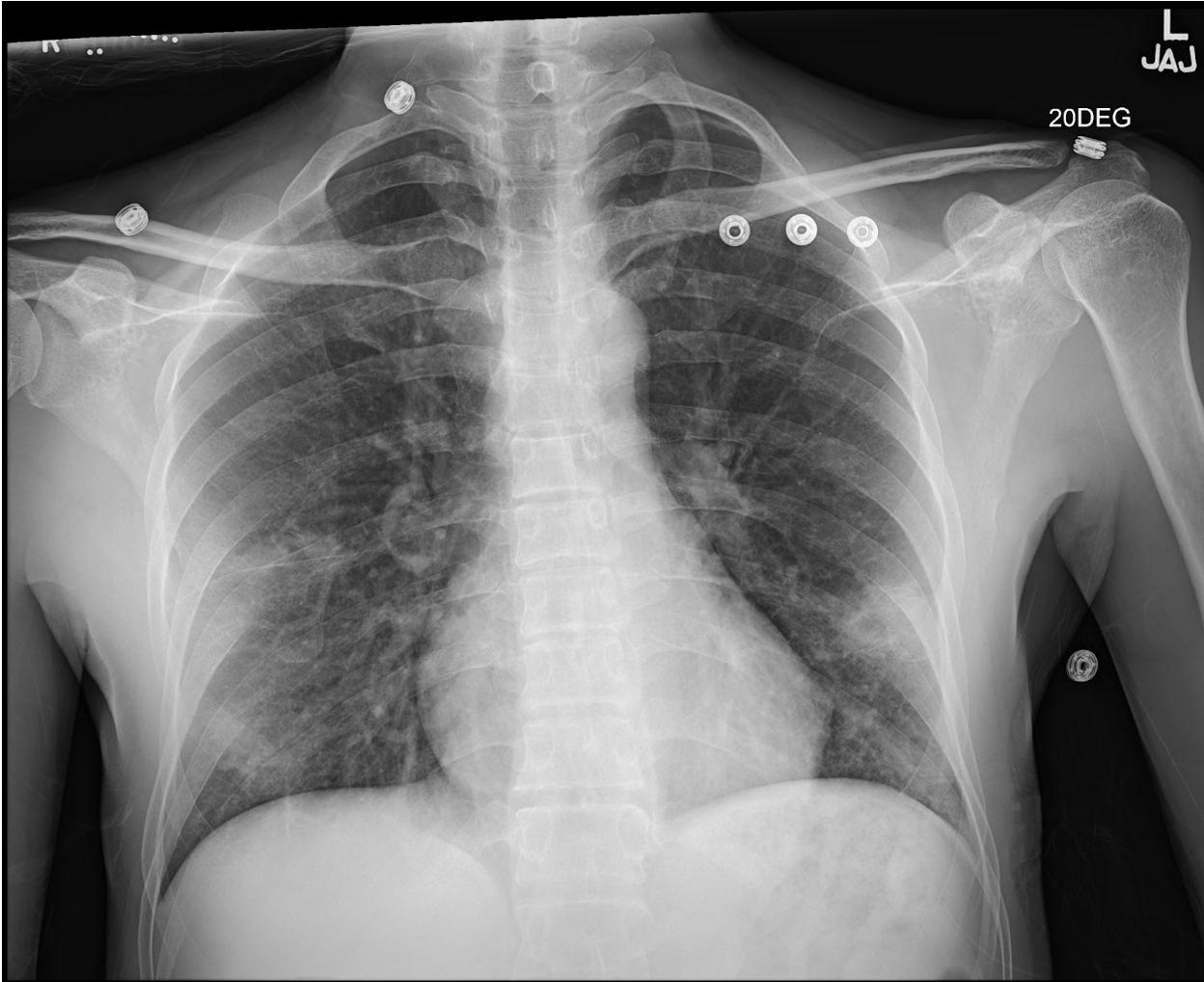

Case Presentation: A 45 y.o. man presented with fever, night sweats, and hemoptysis for one week. He had immigrated to the United States from Mexico 4 years prior. Initial laboratory evaluation was notable for c-reactive protein 134.3mg/dL (normal: < 8mg/dL) and D-dimer 1646ng/mL (normal: < 500ng/mL). Chest CT showed multiple focal regions of consolidation with central cavitation. Quantiferon gold test was positive. Three induced sputum samples were negative for acid-fast bacilli stain, and cultures were negative for M. tuberculosis. CT-guided biopsy was non-diagnostic, showing acute and chronic inflammation with fibrosis and focal hemorrhage. Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage was also nondiagnostic. Extensive evaluation for infectious and noninfectious etiologies, including nontuberculous mycobacterium, endemic fungi, endocarditis, vasculitis, and malignancy, were unrevealing. Given clinical and radiologic evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), exposure risk factors, and absence of another more likely diagnosis, the patient was initiated on empiric antitubercular treatment with rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for presumptive culture-negative TB. After one month of treatment, he reported full resolution of his symptoms, and chest x-ray showed marked improvement in his cavitary nodules. The diagnosis of culture-negative TB was confirmed, and he completed 6 months of treatment.

Discussion: Culture-negative TB is a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for internists as it lies outside the classic binary of latent infection and active disease. A recent systematic review found that patients with clinical and/or radiographic evidence of active TB and negative sputum cultures have a high risk of progression if left untreated, suggesting that culture-negative TB represents an early disease state on a continuum of infection to active disease. Thus, early recognition and treatment is imperative to minimize morbidity and community transmission. Unfortunately, no consensus management guidelines for culture-negative TB exist. In early trials, multi-drug regimens were far superior to single agent isoniazid in reducing progression to culture-positive TB. Current recommendations from the CDC support 4 months of combination therapy, which was shown to have comparable outcomes to nine-month regimens in cases of culture-negative TB in Hong Kong in the 1980s. Our patient had rapid improvement after only 1 month of treatment, supporting that prolonged treatment may not be required. Notably, cross-sectional studies demonstrate that patients with culture-negative TB are less symptomatic at diagnosis. Our own patient reported minimal symptoms that did not impact his day-to-day activities. He felt that the pill burden, drug toxicity, and medication costs of a 6-month treatment regimen were out of proportion to his clinical picture. Shorter regimens for patients with culture negative TB could ameliorate these patient concerns, but clinical trials are needed to evaluate their efficacy.

Conclusions: Culture-negative TB is an under-recognized disease state on the continuum of TB infection to active disease. The diagnosis can be difficult and relies on the clinical acumen of the internist. When hospitalized patients have negative cultures, but clinical suspicion for TB remains high, internists should have a low threshold to consult an expert in TB. Data supports treatment with combination anti-tubercular therapy for 4-6 months.