Background: Hospitals around the country are facing patient flow issues. Late discharges on the inpatient floors are thought to contribute to overcrowding in the emergency department and increased evening admissions (Wertheimer, 2014). This can lead to decreased quality of care, patient satisfaction, and increased length of stay. Some hospitals have attempted to promote early discharges to combat this problem. This concept is based on the assumption that earlier discharge may lead to a reduction in overall length of stay for patients on general medicine units and decrease emergency department overcrowding (Yu, 2014).

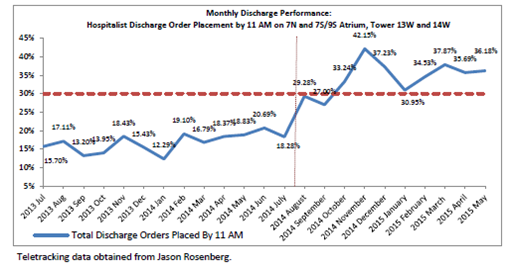

Purpose: Historically, at our institution, an urban academic medical center, the rate of discharge orders placed before 11 am has been about 15%. It was hypothesized that physician rounding patterns designed to accommodate both clinical care and the education needs of trainees contributed to late discharges. To address this possible constraint and improve patient flow, we changed physician rounding practices to prioritize discharges as opposed to admissions.

Description: The goal of our intervention was to increase the percent of general medicine inpatients with a discharge order before 11am to 30%. To achieve this, we took a multi-pronged approach. First, we developed a ‘best practices’ approach that shifted the paradigm for conducting morning rounds from prioritizing new admissions to prioritizing early potential discharges. This protocol also called for 3PM rounds to identify and prepare potential early discharges for the next day. We disseminated our approach to all Division of Hospital Medicine attendings via group meetings and integrated the goal of 30% discharge orders before 11am into the bonus incentive. Medical residents were educated and oriented to the new rounding approach on a monthly basis.

Data was collected on the percent of discharge orders by 11am by attending, and distributed on a monthly basis to faculty and residents. Data was also collected on actual time of discharge, average length of stay, patient satisfaction, and 30 day readmission rates.

Conclusions: In the fiscal year prior to our intervention 16.8% of discharge orders were placed before 11 am. In the ten months after our intervention this rose to 36.18%. Length of stay decreased from 3.53 days to 3.4 days post intervention. However, the average actual time of discharge declined by only 28 minutes (from 3:50PM to 3:22 PM). In addition, after implementation of our intervention we saw a rise in time between placement of the discharge order and actual discharge (from average of 144 minutes to 155 minutes). No effect on patient satisfaction or 30 day readmission rates was noted.

To cite this abstract:

Doctor’s Orders: An Intervention to Achieve Earlier Discharge Times at an Academic Medical Center.

Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2016, March 6-9, San Diego, Calif..

Abstract 5Journal of Hospital Medicine, Volume 11, Suppl 1.

https://shmabstracts.org/abstract/doctors-orders-an-intervention-to-achieve-earlier-discharge-times-at-an-academic-medical-center/.

April 19th 2024.