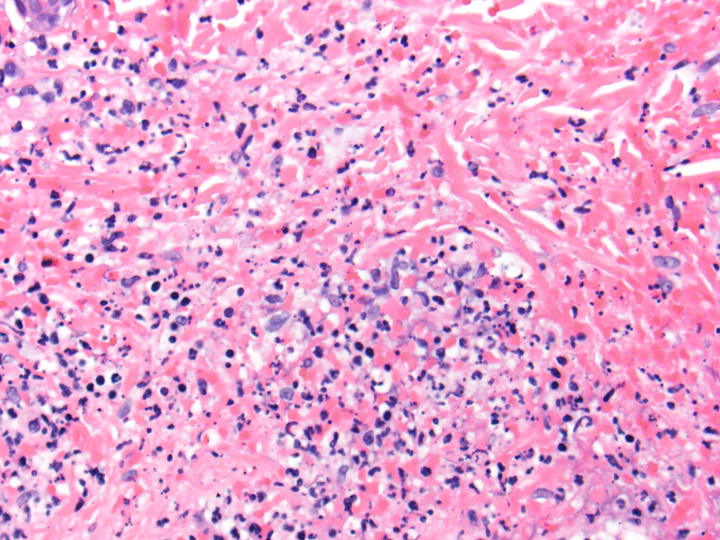

Case Presentation: A 69 year-old man presented after experiencing fatigue and fever for two days. He complained of accompanying dyspnea with decreased exercise tolerance and new four-pillow orthopnea. He had a history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease status-post multi-vessel coronary artery bypass graft, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) for primary prevention, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. On arrival, he was afebrile but hypotensive to the 70s/40s. He was initiated on broad-spectrum antibiotics with vancomycin and cefepime and given crystalloid for sepsis. Two sets of blood cultures showed growth of Staphylococcus aureus prompting a transesophageal echo that showed a small mitral valve vegetation. Antibiotics were narrowed to intravenous nafcillin once sensitivities resulted, and the ICD remained in place. On hospital day 16, he developed a new, tender rash with purpuric papules and plaques with scattered petechial macules on the dorsum of bilateral feet, including cuticles of the toes. Histopathology of a lesion biopsied from his leg revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Repeat transesophageal echo revealed vegetations on the aortic valve and ICD wire. The ICD was removed via transvenous lead extraction. He suffered no complications and was discharged to complete six weeks of intravenous cefazolin.

Discussion: Daily thorough physical examination of patients on a medical service is an essential component of patient care. In the current practice model of hospital medicine, management of patients requires communication between primary teams and numerous subspecialists; changes in clinical status must be communicated, and in this case a new physical exam finding prompted a multi-disciplinary discussion that altered the patient’s treatment plan to pursue immediate ICD extraction. Skin manifestations of endocarditis are a rare entity, with a prevalence of Janeway lesions of approximately 5% and Osler’s nodes up to 10%. Clinical appearance of Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions can be similar; both lesions can occur in similar locations throughout the body, including the fingers and tips of toes. Osler’s nodes tend to be painful and associated with subacute endocarditis, while Janeway lesions are painless and are seen in acute endocarditis. Histologic findings often overlap and include leukocytoclastic vasculitis with or without microabscess formation. Patients with skin findings are observed to have a higher risk of secondary complications. Patients may or may not grow pathologic microorganisms on culture collected from the skin lesions. In patients with positive blood cultures without evidence of device-related infection or infective endocarditis, initial management with antimicrobial therapy is still an option. The likelihood of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device (CIED) infection is higher in patients with bacteremia due to staphylococcal species, with approximately 35% confirmed bacteremia. Transesophageal echo is required to work-up bacteremia, though vegetations on a lead are only consistent with and not diagnostic of a lead-related endocarditis. Confirmed CIED infection mandates complete device removal.

Conclusions: The importance of the physical exam in infective endocarditis should not be underestimated, with skin manifestations an overall rare but very significant finding. In this case, a new physical exam finding prompted a discussion regarding the necessity of CIED removal.