Background: Microaggressions were first described by Dr. Chester Pierce in 1997 as “subtle and stunning” daily racial offenses and then by Sue et al. as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional” which often target marginalized groups. Many studies have demonstrated the harmful effect of microaggressions on the target but evidence about curricula that foster change in those responsible for microaggressions is lacking. Building upon the curricula created by Sandoval et al. to teach medical students how to address microaggressions in the learning environment and the curriculum by Fisher et al. which taught this to internal medicine residents, a 90-minute curriculum was offered to all attendings and trainees at an urban teaching hospital over the course of two years from 2020 to 2022. The sessions were held remotely on Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Purpose: This study aimed to assess the impact of a 90-minute microaggression response training on participants’ self-efficacy to respond to microaggressions, regardless of their role as the target, witness, or perpetrator.

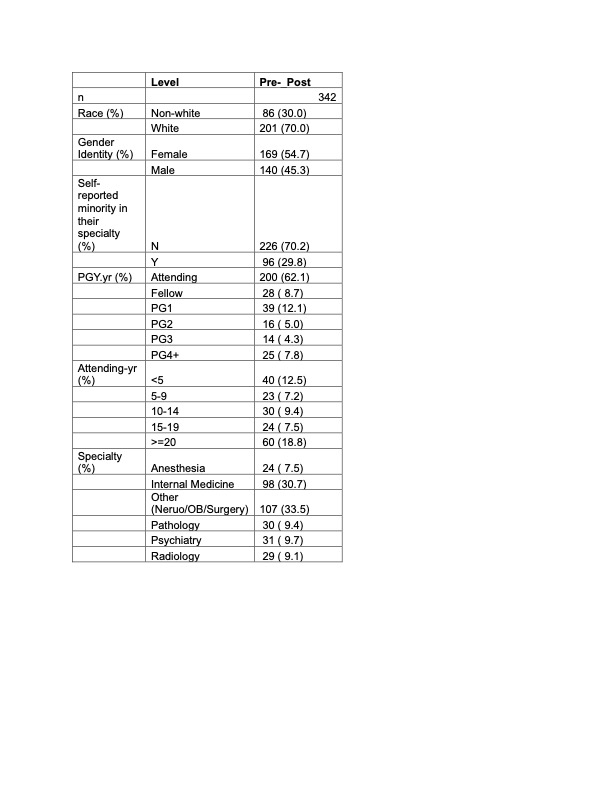

Description: Using a microaggression response toolkit, participants engaged in role-playing exercises during the sessions. Pre and post-surveys were designed and administered to assess the effect of the workshop.Study participantsDemographic analysis revealed a diverse sample consistent with the institution’s overall composition, with 30% self-identified as non-white and 54.7% as female. 62% were attendings. 31 % of participants were from the Department of Medicine.. (See Table 1) Responses were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed rank sum test on individual imputed datasets and test statistics were pooled in accordance with Rubin’s rule. The significance level is set at 0.05.

Conclusions: Compared to before the workshop, participants thought that they were better able to respond to microaggressions when they were a target of a microaggression (p< 0.00001). Similarly, participants reported an improved ability to respond to microaggressions when they witnessed them (P< 0.0001). More importantly, they also reported an improved ability to respond to microaggressions when they perpetrated the microaggression (P< 0.001).A potent way to decrease the incidence of microaggressions and the harm they cause is to decrease the frequency with which one is the source of them, as well as enhance one’s ability to respond to one’s own microaggressions. Our study is one of the few studies that documents the increased self-efficacy of participants to respond to their own microaggressions after an intervention. Given the hierarchy that exists in medicine and the importance of faculty in creating safe educational spaces, future work will focus on ways in which attendings improve their ability to recognize and respond to their own microaggressions.