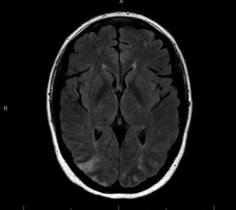

Case Presentation: A 46-year-old female with history of rheumatoid arthritis and asthma presented with chest and back pain to an outside facility and was evaluated for acute coronary syndrome and cholecystitis. Patient’s absolute eosinophil count (AEC) was 1.76 at that time. Patient was re-admitted with altered mental status and vomiting. Her AEC was 41. Strongyloides IgG titer was positive, but EGD showed no strongyloidiasis. Other infectious work up was negative. TTE showed pericardial effusion, CTA was negative for PE, and brain MRI showed embolic infarcts. A bone marrow biopsy showed increased eosinophils only. Patient was then transferred for higher level of care. Upon arrival, patient was ill-appearing, afebrile, tachycardic, normotensive with mild hypoxia and multiple ecchymosis. Physical exam was otherwise unremarkable. Labs showed WBC 28.6, AEC of 8.85, normal BUN/Cr ratio, Alk Phos 444, AST/ALT 45/70, INR 1.4, CRP 36, GGTP 507, troponin 431, PR3 >8.0, MPO .2, elevated strongyloides IgG antibody, decreased C4 and C3 complement, and normal total IgE. Antiphospholipid syndrome work up, cancer cytogenetics, fungitell, protein electrophoresis, cyclic citrullinated peptide, rheumatoid factor, blood cultures and stool parasites were normal. Skin biopsy showed vascular thrombosis, not vasculitis. CT Head/MRI/MRA Brain showed a watershed infarcts. TTE showed an EF at 61%, moderate pericardial effusion, patent PFO, SVC vegetations vs. thrombus, and thick mural echogenicity compatible with Loeffler’s endocarditis. Cardiac MRI showed extensive thrombi. Repeated CTH showed hemorrhagic conversion. Patient was treated with steroids, hydroxyurea, albendazole, and meprolizumab. Patient passed despite wide variety of aggressive treatment.

Discussion: We report a fatal, complex case of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). HES is defined as hypereosinophilia with an AEC >1500 cells/microL and organ dysfunction. Our differential diagnosis included eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), myeloproliferative process, helminthic infection, and drug hypersensitivity reaction. EGPA was unlikely due to the lack of involvement of small vessels, persistent elevation of eosinophils despite high dose steroids, and a skin biopsy that showed thrombotic vasculopathy but no vasculitis. Serologic rheumatologic evaluation and the intramural thrombosis were not consistent with vasculitis. Myeloproliferative and neoplastic work up was unremarkable. Bone marrow biopsy and cytogenetic studies on peripheral blood for JAK2, FGFR1, PDGFRB, FLT3 were negative. The patient had positive strongyloides antibodies; however, EGD, colonoscopy, and stool examination did not show strongyloidiasis. Drug-induced eosinophilia was less likely given lack of prominent rash or facial edema suggestive of DRESS and negative tryptase. Thus, diagnosis of idiopathic HES was made.

Conclusions: HES is a rare and devastating disorder presenting with common symptoms misleading to the diagnosis of other, more common diseases. Patient history, high level of suspicion, and a comprehensive differential diagnosis and workup lead to the diagnosis of idiopathic HES. Early diagnosis and treatment may enhance the probability of remission without predicting cases of high mortality.