Background: Current literature shows that many graduating health-professional students are not adequately trained to identify safety hazards [1]. With early integration of patient safety education in medical student education, we hope to reduce the occurrence of adverse events longitudinally throughout an individual’s medical career. Data demonstrates that patient safety simulations are an effective method to train medical professional students in identifying patient safety events [2]. Escape Rooms are an entertaining activity for teambuilding, improving communication, and developing memory skills. This project aimed to utilize this format to mimic a high-stakes hospital environment while teaching basic patient safety concepts and prove it to be an effective teaching tool for patient safety.

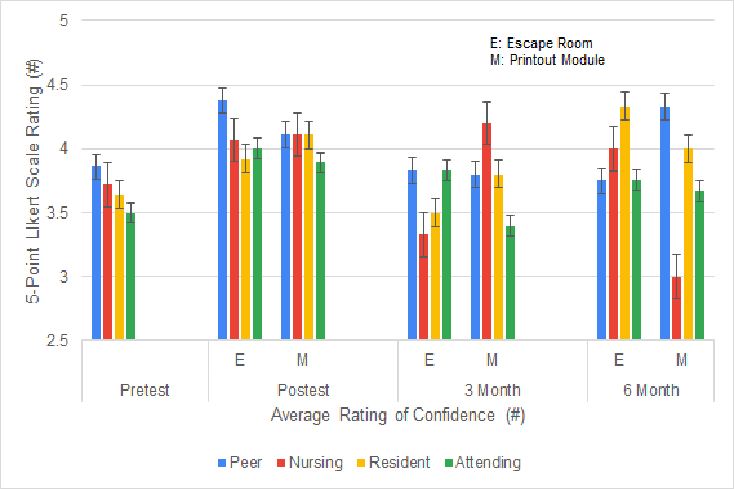

Methods: Students were recruited to participate in a printout module (control) or an Escape Room (experimental). The Escape Room focused on three major themes: patient identification, patient advocacy, and physical harm. We highlighted errors that included matching patient information, bringing awareness to gender pronouns, and identifying hazardous conditions. The modules were adapted from the standardized training students are required to complete at Rush University. A pretest was administered prior to randomization to assess and establish a baseline knowledge of patient safety, attitudes, and self-reported confidence based on a 5-point Likert scale towards patient safety. Participants were randomly assigned to either the module or Escape Room simulation. The Escape Room attendees also participated in a debrief following their simulation. After completion of either one, participants completed a posttest. Both groups also went into a standardized simulation room to assess accuracy in identifying patient safety concerns as a team. A 3-month and 6-month follow up survey was completed. Data was analyzed using unpaired sample t-test and qualitative analysis.

Results: The study consisted of 22 participants divided into the Escape Room (n=13) and the printout module (n=9). A 3-month and 6-month follow up survey were sent out with notable loss to follow up at 3 month (n=11) and 6-month (n=7). The initial simulation assessment following either intervention showed each group received the majority of the points out of twelve with no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p=0.06). Individual survey questions rating confidence in speaking up about patient safety were not statistically significant, when comparing pretest and posttest results. Overall, the average rating pretest self-reported confidence in speaking up about errors was 3.68 with posttest average of 4.08 (p=0.0003).

Conclusions: Our data shows promise that patient safety can and should be talked about more in medical education. While even something as simple as a module to discuss the topic can prove to be beneficial, students collectively showed interest in an Escape Room learning format; feedback provided included “so much fun,” “very interactive,” “fun way to learn about patient safety.” The lack of difference between both groups can also be attributed to the small sample size. We hope to increase our recruitment efforts to continue expanding the data collection and encourage stronger follow up to study long-term retention. If we can prove the efficacy of escape rooms as learning tools, this project has the potential to be implemented into the medical student curriculum and expanded to other various topics within medicine.