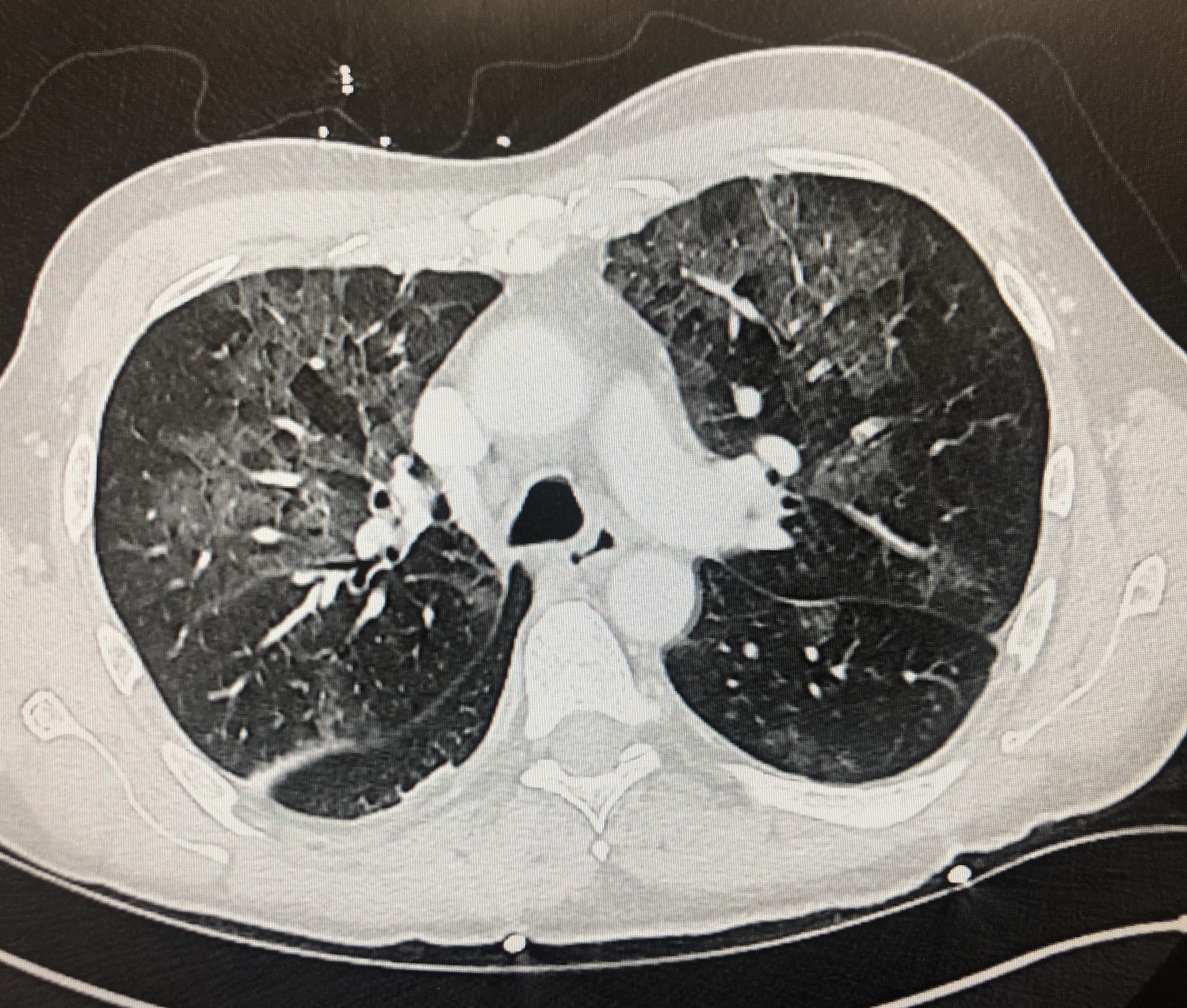

Case Presentation: A 59-year-old gentleman with newly diagnosed cirrhosis presented to the emergency room after 5 episodes of frank hematemesis. He had a recent screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy notable for portal hypertensive gastropathy without varices. On admission, he was hemodynamically stable with hemoglobin near his baseline. He was started on a pantoprazole infusion and IV ceftriaxone. Hours later, he developed large volume hematemesis with a precipitous drop in hemoglobin and underwent massive transfusion protocol and intubation. Upper endoscopy revealed large gastric varices with evidence of prior bleed. Definitive hemostasis could not be achieved, and Interventional Radiology emergently performed a plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (PARTO) procedure that successfully sclerosed the culprit varices. The patient’s condition stabilized and he was extubated. However, the next day he developed a fever and new oxygen requirement. He was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics but continued to have fevers (Tmax 101F) for five days. Chest CT demonstrated multilobar infiltrates and ground-glass opacities (image 1); there was no evidence of pulmonary emboli. A comprehensive infectious workup was negative, including a respiratory pathogen nucleic acid panel, COVID-19 PCR x3, blood, sputum and urine cultures. Atypical pulmonary edema was considered but failed to explain the patient’s fevers. Aspiration pneumonitis was not consistent with the predominantly upper lobe distribution of infiltrates on CT. Ultimately, he was suspected to have had a systemic reaction to the sclerosing agent from the PARTO procedure. His condition improved in the next two days and he was afebrile and off of oxygen by discharge.

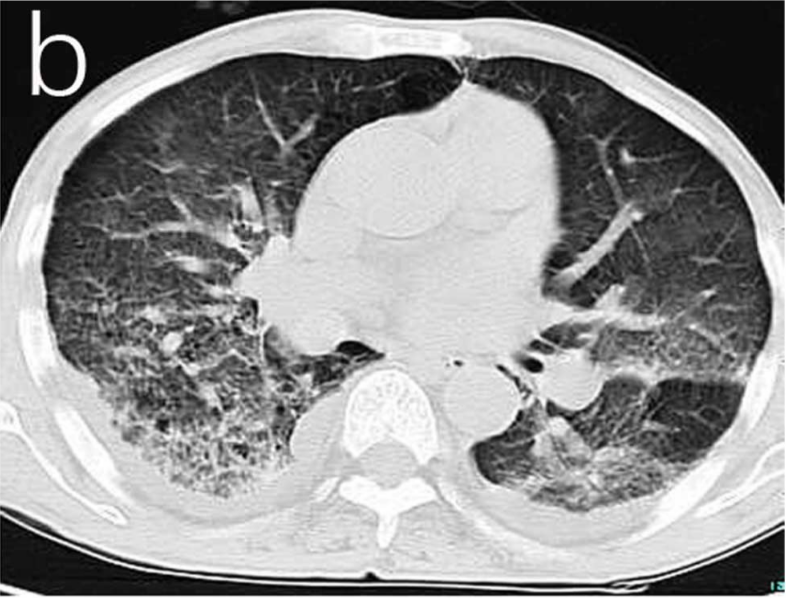

Discussion: Consideration must be made for non-infectious causes of fever in the ICU, such as transfusion reactions, venous thromboembolism, and drug-reactions. The PARTO procedure in this case involved a sclerosing agent called lipiodol. There is a paucity of literature outlining the side effects of lipiodol in PARTO procedures; however, there are many publications on systemic and pulmonary side effects of its use in transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) procedures for hepatocellular carcinoma. Post-TACE pulmonary complications are rare and range from mild hypoxia to chemical pneumonitis, lipoid pneumonia, pulmonary oil embolism, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute lung injury, and death (1). These complications are thought to be due to chemical injury from the migration of the lipiodol to the lung vasculature (1). Acute lung injury has a high mortality rate and includes the following radiologic abnormalities: pleural effusion, diffuse pulmonary infiltration (image 2) similar to that seen in our patient, and accumulation of lipiodol in the lung field (2). The dose of lipiodol has been shown to be a significant risk factor associated with post-TACE fever and pulmonary complications (3).

Conclusions: Fever and pulmonary complications from lipiodol should not only be considered after TACE, but also after PARTO procedures. This can help reduce anchoring on infectious etiologies in these patients, and can help guide care for those who are critically ill who may benefit from additional treatments such as intravenous steroids. Successful steroid therapy has been shown in chemical pneumonitis and ARDS after lipiodol use, but efficacy has yet to be proven (1). In the case of our patient, steroids were considered but deferred given his clinical improvement.