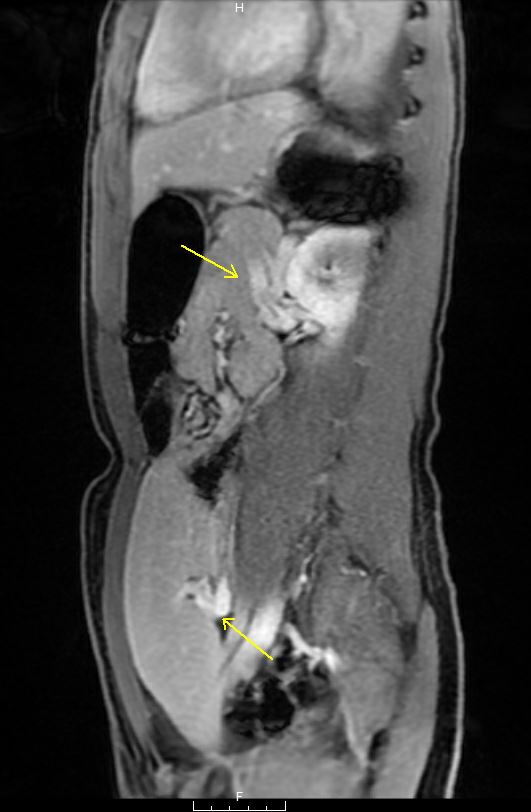

Case Presentation: A 14-year-old previously healthy male presented to a community hospital for sudden repeated episodes of initially non-bloody, and then grossly bloody, emesis. He denied sick contacts, travel, significant NSAID use, alcohol consumption, and caustic ingestions. On presentation, he had normal vital signs, mild epigastric tenderness, and heme-positive dark stool. His labs were notable for hemoglobin 8.8 g/dL, platelets 148 K/uL, and normal complete metabolic panel (including liver panel), lipase, and coagulation panel. He had 100 mL of witnessed emesis with clots and received a fluid bolus, one unit of packed red blood cells, pantoprazole, and octreotide.On transfer to a tertiary pediatric hospital, repeat hemoglobin was 8.4. He remained asymptomatic with normal vital signs for 12 hours and was initially believed to have a Mallory-Weiss tear, NSAID-induced gastritis, or peptic ulcer disease. However, he abruptly developed severe hematemesis with an estimated volume of 2 L, with associated pallor, diaphoresis, altered mentation, hypotension, tachycardia, and repeat hemoglobin 7.3. He was emergently fluid resuscitated and transferred to the intensive care unit for hemorrhagic shock, requiring activation of the massive transfusion protocol. Abdominal ultrasound revealed splenomegaly and dilation of the portal vein and splenic hilar veins despite normal hepatopedal flow, suspicious for portal hypertension. He underwent endoscopy with epinephrine injection and clipping of a solitary raised erythematous lesion in the gastric cardia, thought to be a varix or arteriovenous malformation. Computed tomography done to better characterize the gastric lesion demonstrated hepatosplenomegaly, dilated portal vein, and gastric submucosal/perigastric/perisplenic varices. Magnetic resonance angiogram/venogram was negative for arterial or venous thrombosis but uncovered displacement of the spleen in the left hemipelvis, consistent with a wandering spleen (WS).Before planned splenopexy occurred, he again suffered hemodynamically significant hematemesis, triggering reactivation of the massive transfusion protocol and emergent exploratory laparotomy, splenectomy, and gastrotomy with suture ligation of bleeding fundal gastric varices. He recovered well and was discharged 9 days later.

Discussion: While hematemesis from varices is common in adults with portal hypertension, hematemesis in pediatrics is more frequently due to Mallory-Weiss tears or peptic ulcer disease. WS is a rare phenomenon wherein a spleen’s inadequate ligamentous attachments allow it to migrate and undergo torsion that can cause sinistral (left-sided) portal hypertension and subsequent varices. WS usually presents as abdominal pain and/or mass and is then discovered on imaging, sometimes complicated by varices. Fewer than 10 cases have been published in which the presenting symptom of WS was hematemesis. This case constitutes the first male report and second pediatric report. It differs from prior reports by its epidemiology (usually 20-50-year-old women), location of variceal bleeding (gastric cardia in addition to the typical fundus), and severity.

Conclusions: This case illustrates that 1) variceal bleeding is an etiology of hematemesis that cannot be missed regardless of age or the absence of comorbidities frequently associated with portal hypertension, and 2) WS is an uncommon entity that can rarely present as severe hematemesis and shock from variceal bleeding due to sinistral portal hypertension.