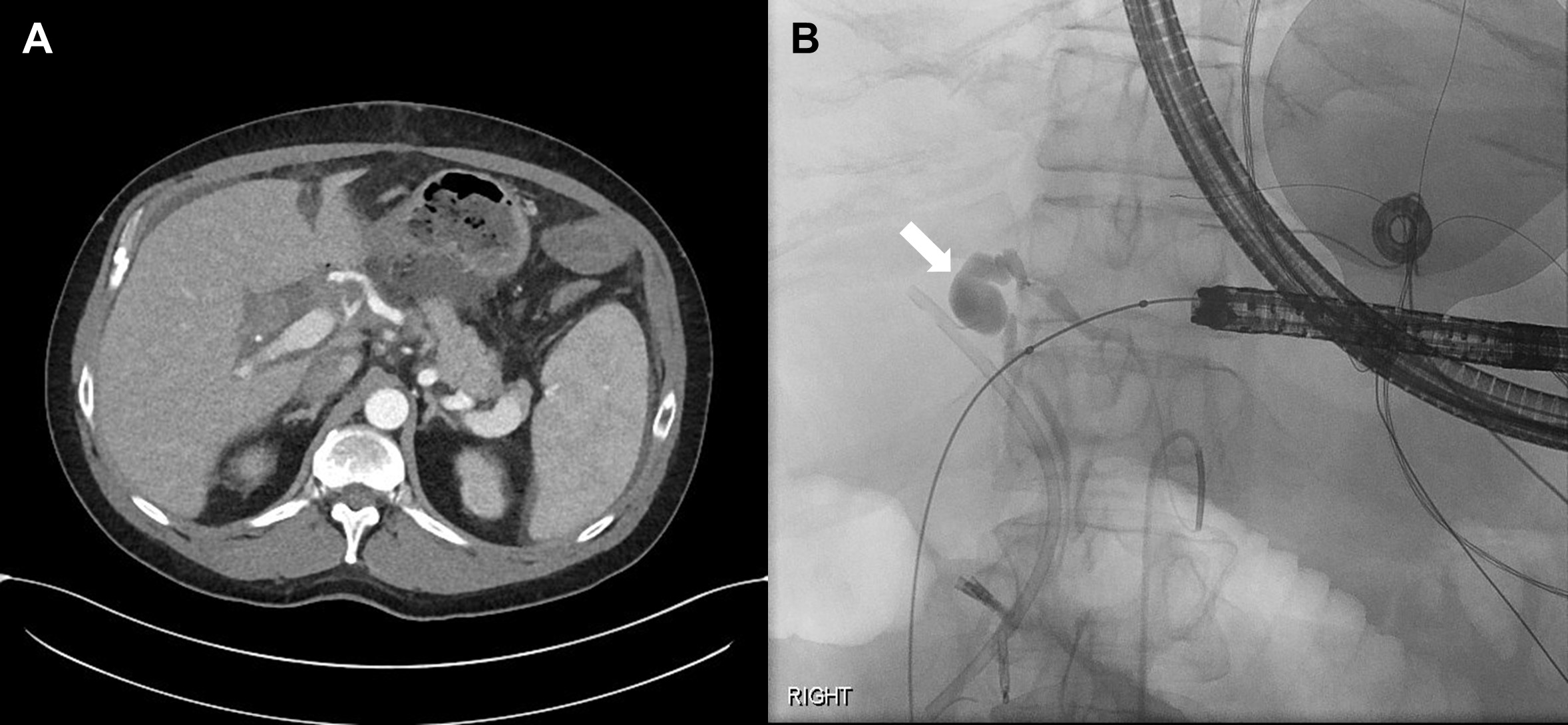

Case Presentation: A 49-year-old male with history of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma secondary to alcohol use and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, who underwent liver transplant 1 month prior that was complicated by a bile leak at the biliary anastomosis requiring stenting, presented to the hospital for sudden onset of fever, chills and headaches. He was on immunosuppression, and reported nausea and right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort radiating to his back. He denied cough, sore throat, emesis, diarrhea, dysuria, new rash, chest pain and dyspnea. He was afebrile (37.8°C), tachycardic (112bpm), normotensive (126/77mmHg), and mildly tachypneic (20). He was in distress, but his mentation was appropriate, with abdominal exam revealing mild distension radiating towards the back. There was no costovertebral angle tenderness. Labs revealed a hemoglobin of 8.1 (10.8 on week prior), platelets of 93 (201 one week prior) and a WBC count of 9.9. LFTs were remarkable for an elevated total bilirubin of 3.5 (direct component: 3.5), alkaline phosphatase of 366 (increased from 192), and an ALT and AST of 124 and 145, respectively. Lactate (1.6) and (1.3) were normal. Urine analysis did not show pyuria, and chest x-ray was negative. He was found to have Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia and started on antibiotics. CT abdomen and pelvis showed a new common hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm with no definite contrast extravasation to suggest active hemorrhage. The patient subsequently developed large volume melena and hematemesis and experienced syncope. He was transferred to the ICU for hemorrhagic shock and was intubated. He had PEA arrest 4 times, receiving a total of 77 units of blood products (40 RBC, 7 PLT, 26 FFP, and 4 Cryoglobulin). On EGD, the active bleeding was thought to be coming from the duodenum with high suspicion for hemobilia. Emergent celiac angiogram confirmed a large ruptured hepatic pseudoaneurysm with brisk bleeding into the bile duct presumably through the anastomosis that had a prior leak, and then into the duodenum. He underwent hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm embolization. Liver fluid grew Streptococcus anginosus. While subsequent MELD score was 35, reassuringly, he was extubated, remained hemodynamically stable, and underwent a second liver transplant. He did well post-operatively.

Discussion: Hemobilia is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleed which occurs when there is a pathological connection between the biliary tree and the vasculature, permitting bleeding into the biliary system. The majority of cases are due to iatrogenic instrumentation, trauma, and malignancy, where the etiology of hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm rupture is exceptionally rare. Hemobilia can present with the classic triad of jaundice/elevated bilirubin, right upper quadrant pain and upper GI bleed, which was seen in our patient. The patient’s history of liver transplant complicated by biliary leak and stenting likely predisposed him to both the hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm and fistula formation leading to the hemobilia. Specifically, the complication of hemobilia occurred 1 month after the inciting event which is not uncommon.

Conclusions: We present a rare case of hemobilia caused by hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm rupture. Hemobilia should be in the differential diagnosis for an upper GI bleed, especially in the setting of hyperbilirubinemia, and a recent history of liver transplantation and/or biliary tree instrumentation.