Background: Medication reconciliation programs are a well-recognized important tool in reducing medication discrepancies and subsequently decreasing patient harm, particularly at transitions of care. Medication reconciliation programs have demonstrated error reductions upward of 66% [1-4]. 39% of prescription medication history errors have the potential to cause moderate or severe discomfort or deterioration in a patient’s condition [2]. Due to the increased opportunity for error and the risk associated with these errors, there is a growing pool of literature on the topic of medication history programs but little data on what specific factors place an individual patient at higher risk for medication error upon admission to a hospital. We performed a prospective analysis of 817 patients to identify these factors.

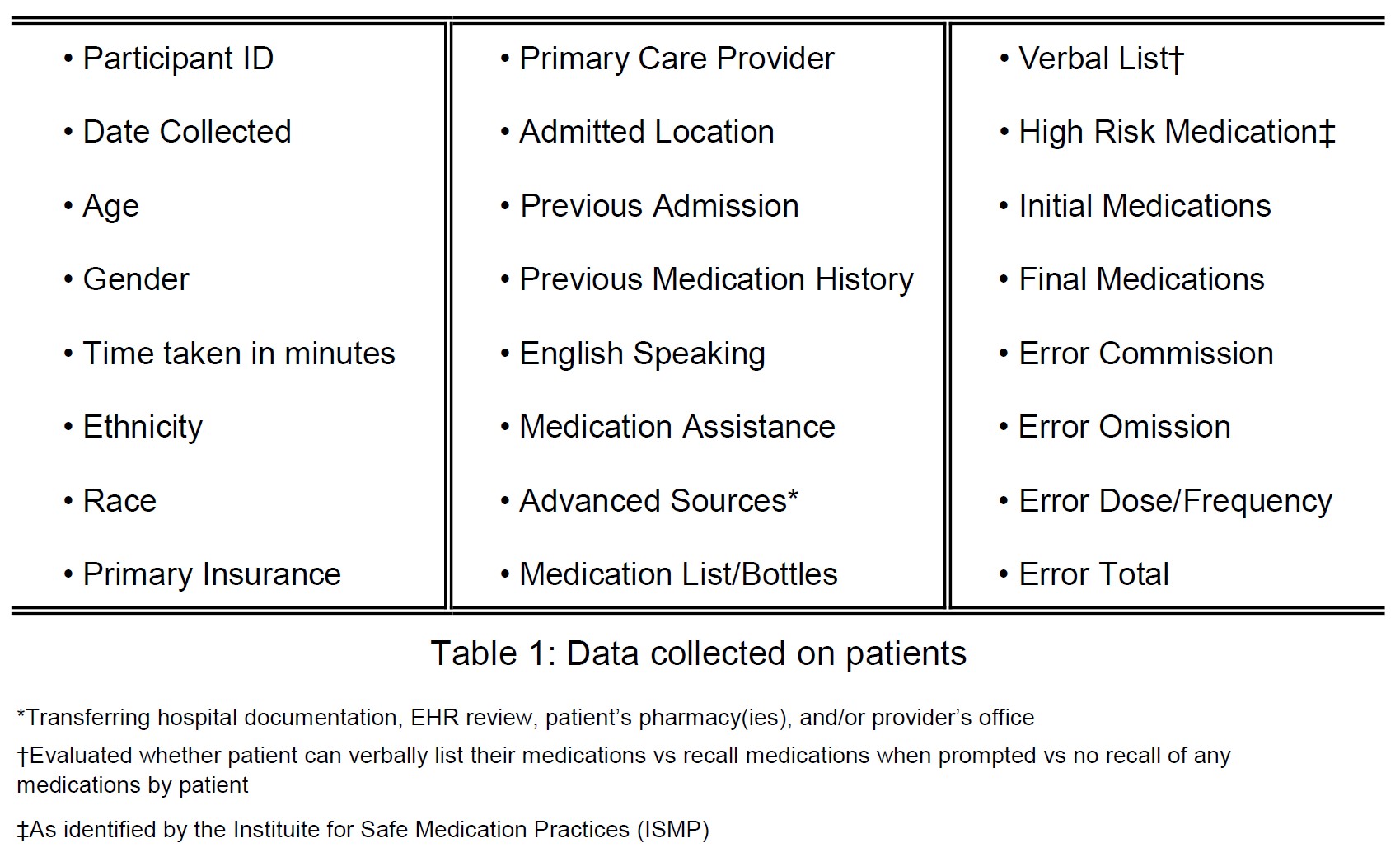

Methods: Medication history technicians (MHTs) at our facility obtained the best possible medication history (BPMH) on adult patients at least 18-years-old; there was no gender, ethnic background, or health status exclusions. Medication histories were obtained in our emergency department, all general medical floors, and our Coronary Care ICU. The BPMH was obtained in accordance with MARQUIS Implementation Manual guidelines [5]. Multiple data points were collected on each patient as outlined in table 1. 817 patients were observed over a 7-week period. Poisson regression was a poor fit for the data, so a negative binomial regression model was formed. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was applied to develop a reduced model that eliminates variables from table 1 that were not significant. The likelihood ratio test was then applied to verify the full model was not significantly better than the reduced model.

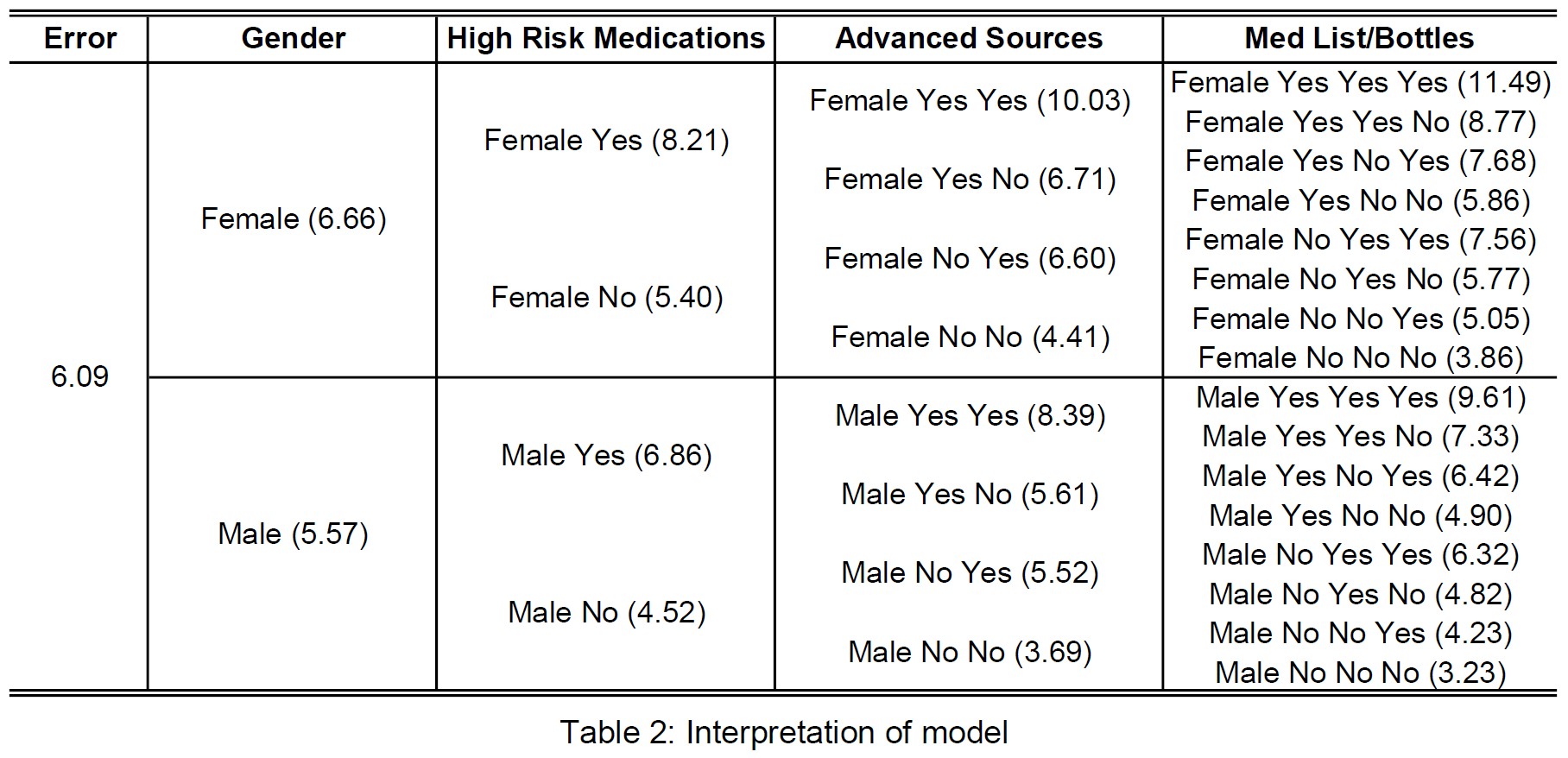

Results: Our negative binomial regression reduced model identified the following factors that contribute most to medication errors on admission to the hospital (see table 2):• Female gender• High risk medication use• Availability of advanced sources to MHTs• Patient provided medication list/medication bottlesInterestingly, we found that if a patient provided their own medication list or brought their medication bottles to the hospital more errors were identified. However, if a patient was able to verbally list their own medications, they tended to be more accurate. Additional factors that influence medication errors include Medicare/Medicaid insurance coverage, medication assistance required by the patient, and previous hospital admission. Our data also satisfies our intuition that increasing age lead to increase in medication error.It was interesting to note that patients coming outside of our network of Primary Care Providers did not have more errors than those coming from in-network. Our data also suggests admission over the weekend has no effect on medication error. Attempts were made to observe differences in ethnicity, race, and primary language but the homogeneity of our patient population did not allow for significant analysis.

Conclusions: Using our predictive model, we can identify what factors lead to increased medication error. Our model also allows us to identify which factors have little effect on medication error. Further analysis and research may allow us to identify which modifiable factors to target for improvement in a large hospital system or inversely, identify which patients may not need the use of an MHT on admission in a resource-limited organization.