Background: Effective discharge planning requires early identification of patients’ post-acute care needs as well as potential barriers to placement. Housestaff receive little formal training on discharge planning and are instead expected to learn “on-the-go”. At the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs (WLAVA) Medical Center there exists many disposition options that aren’t available to our housestaff at their other training sites. Acceptance criteria for these myriad options are variable and can be overwhelming. Confusion about these options can lead to reduced provider satisfaction, delayed referral placement, and inappropriate referrals leading to longer hospitalizations. One particularly confusing option at WLAVA is the Transitional Care Unit (TCU). TCU accepts patients who have subacute care needs but don’t qualify for other options. From our experience as TCU screeners, we frequently receive inappropriately placed referrals to this service. We hypothesized our algorithm tool could 1) improve housestaff satisfaction and lessen confusion with discharge planning at WLAVA and 2) increase the proportion of appropriate TCU referrals.

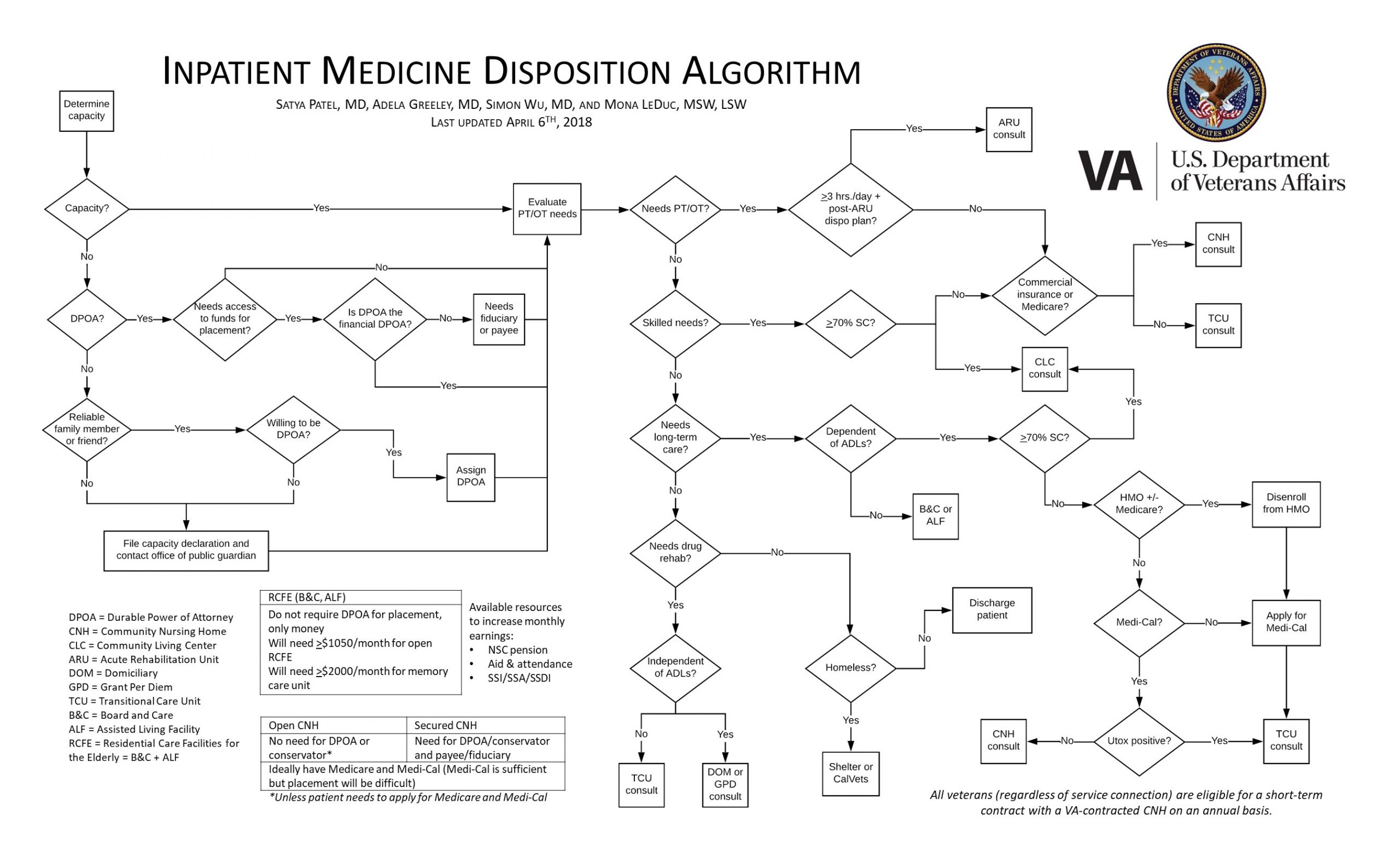

Methods: We developed a visual algorithm tool that outlined acceptance criteria to WLAVA’s many post-acute care options. We rolled this tool out to 2 of the 5 WLAVA medicine teams (ie, the “education” group) over the course of 7 weeks (May-June 2018). We also gave the “education group” a glossary of common disposition-related terms and instructed them on how to use the algorithm. We could not implement our education with the other 3 teams (“non-education” group) due to time constraints; they performed their clinical duties as usual. Housestaff from both groups were surveyed to assess comfort level and satisfaction with disposition at the start and end of their rotations. There were 34 respondents in the “education” group (17 at the start of the rotation; 17 at the end) and 52 respondents in the “non-education” group (28 at the start; 24 at the end). We compared responses between the “education” and “non-education” groups to assess the impact of our algorithm tool. We reviewed all TCU consults received during the study period for appropriateness as judged by the screening hospitalist. Our project was granted “quality improvement” status by our IRB.

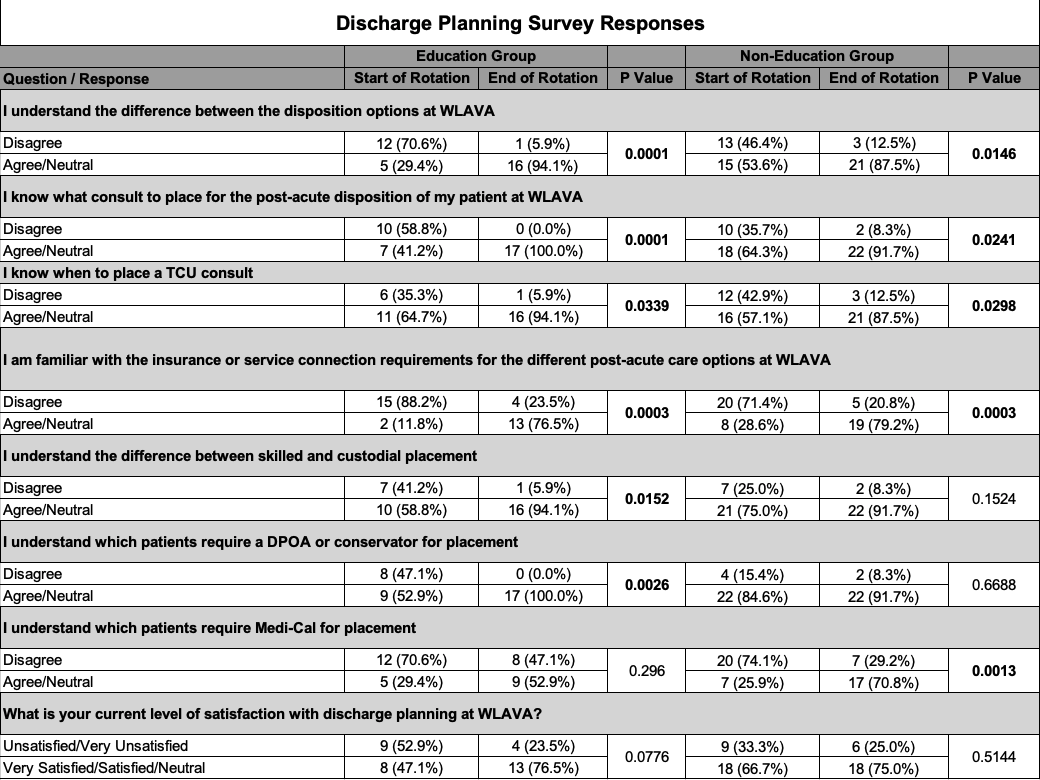

Results: By the end of their rotations, housestaff from both “education” and “non-education” groups showed increased comfort level with most disposition-related survey items (see table). All respondents in the “education” group found the algorithm tool to be helpful. There was no significant difference in comfort level or satisfaction with discharge planning between the 2 groups at the end of their rotations. There was a higher acceptance rate in TCU consults placed by the “education” group compared to the “non-education” group (13/16 vs 8/19, p=0.019).

Conclusions: Our algorithm was considered helpful by residents and was associated with higher acceptance rates of patients to one of WLAVA’s subacute care services. The algorithm’s lack of impact on comfort level and satisfaction with disposition may be explained by the project occurring at the end of the academic year, when housestaff are typically more comfortable with this task. We have since integrated our algorithm into lectures to housestaff at WLAVA to increase formalized teaching on transitions of care. We hope to integrate our algorithm into our interdisciplinary discharge rounds and revise the tool in an iterative manner based on internal feedback received from key stakeholders.