Background: Food insecurity (FI) is “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or…to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways.” FI, a social determinant of health (SDOH), is associated with worse health, education, and socioeconomic outcomes. A validated 2-question survey with high sensitivity and specificity in identifying food insecure families exists. In our system, FI screening was performed intermittently in outpatient and rarely in inpatient settings.

Purpose: An interprofessional team was formed (social work (SW), nursing, physician, and informaticist) to address barriers to inpatient food insecurity screening and implement a screening workflow. The team created the SMART aim: Within 6 months, a best workflow will be created for FI screening of hospitalized children/families on the Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) Service, and >75% of those who screen positive will receive appropriate resources.

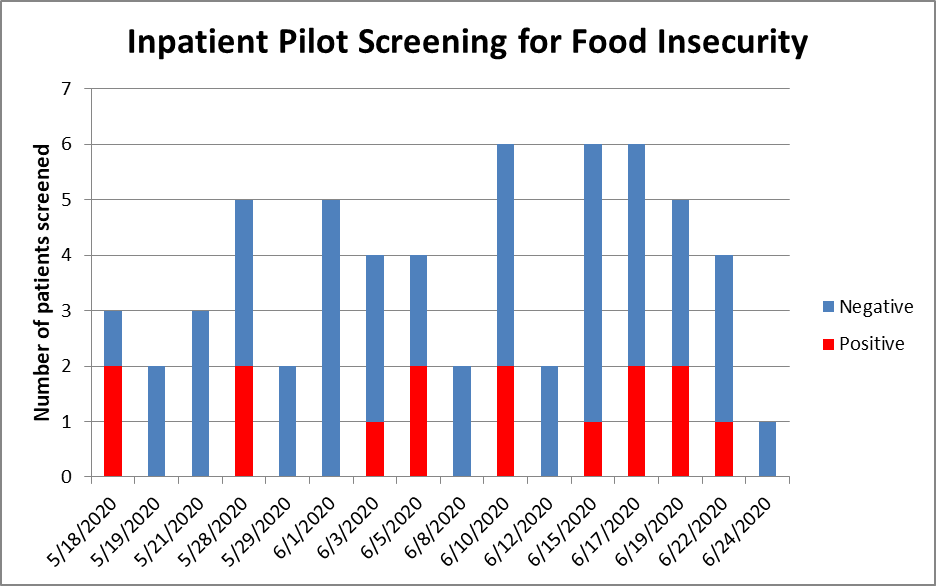

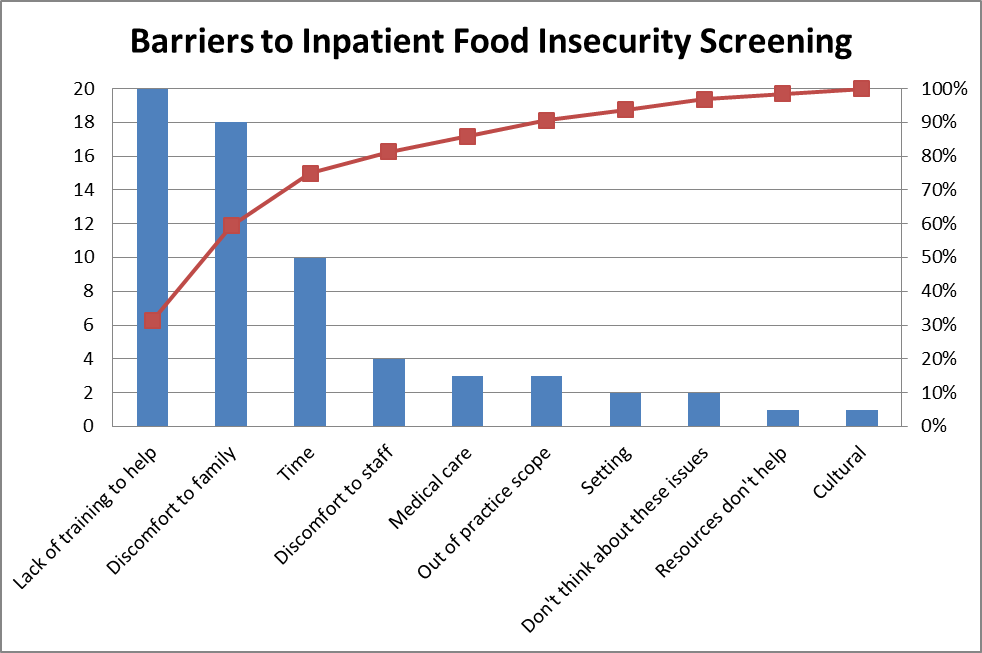

Description: Best practice literature and local data for the tertiary children’s hospital were reviewed. Ishikawa, process map, and Key Driver Diagram were completed. Measures were selected including total and positive number of screenings completed (process) and number of positive screens given resources (outcome). The team also assessed staff and family survey results on perceptions of the screening process (outcome and balancing).Cycle 1: The team created a best workflow from QI tool data: A research assistant (RA) called the family at the bedside phone in the patient room, introduced and completed the 2-question screening, and ended with the family survey. Screening results were entered into the Social History section of the electronic medical record. If positive, the bedside nurse and attending were notified of the results. The attending provided a resource list in English or Spanish to the family. Cycle 2: A pilot convenience screening and survey of 78 families admitted to the medical units on the PHM service was completed May – Sept 2020. Cycle 3: Staff surveys of 56 physicians, nurses, and SW were completed. The team reviewed data; inefficiency was identified. Clinical decision support to automate a SW consult for positive screens went live Sept 2020.Of our 78 patients, 22% screened positive (Figure 1); resources were provided to 100% of these. Nearly all families (99%) and staff (90%) felt asking about SDOH during a hospital stay was important and helpful. Families preferred a survey alone on paper (44%); staff felt a technical device would be the best method (43%). Staff felt that families would be uncomfortable (79%), would not respond truthfully (39%), and would be unreceptive to FI questions (28%). Most staff felt a technical device would abate these concerns. Many staff (44%) felt unequipped to ask about SDOH and provide resources. The most common reasons were lack of training or time and discomfort to family or staff (Figure 2).

Conclusions: We created a screening workflow that demonstrated success identifying FI and exceeded our aim, providing resources to 100% of families with FI. We found FI in 22% of our PHM hospitalized patients, emphasizing the importance of screening. Families and staff rated hospital screening important but ideal screening methods differed. Next cycles include a recently initiated electronic SW consult automation for positive FI screens, addressing family preferred screening methods, and disseminating to other inpatient services.