Background: Hospitalists have been at the frontlines of caring for hospitalized patients with COVID-19, placing unusually high stress on hospital-based providers. Attention to hospitalist well-being and resiliency has been essential. We have engaged in a quality improvement project seeking to measure and, more importantly, improve the well-being of hospitalists at a single, large academic hospital. The project entails a pre-intervention survey, Leadership WalkRounds and Listening Sessions, followed by a post-intervention survey. Here we report on the initial results: the baseline burnout scores.

Methods: After investigating various tools for the measurement of burnout, we created a 30-item survey which included the 5-item Emotional Exhaustion scale, derived from the Maslach Burnout Inventory. This scale has been independently validated and utilized widely for the measurement of healthcare workers’ emotional exhaustion. Our anonymous survey also included basic demographics, questions about work-place violence, self-reported medical errors, and a section for free-text responses. The survey was dispersed to hospitalists at an academic hospital in Spring 2022 and has allowed us to gain an understanding of the baseline level of burnout of the group. The study was given exempt status through the university’s institutional review board.

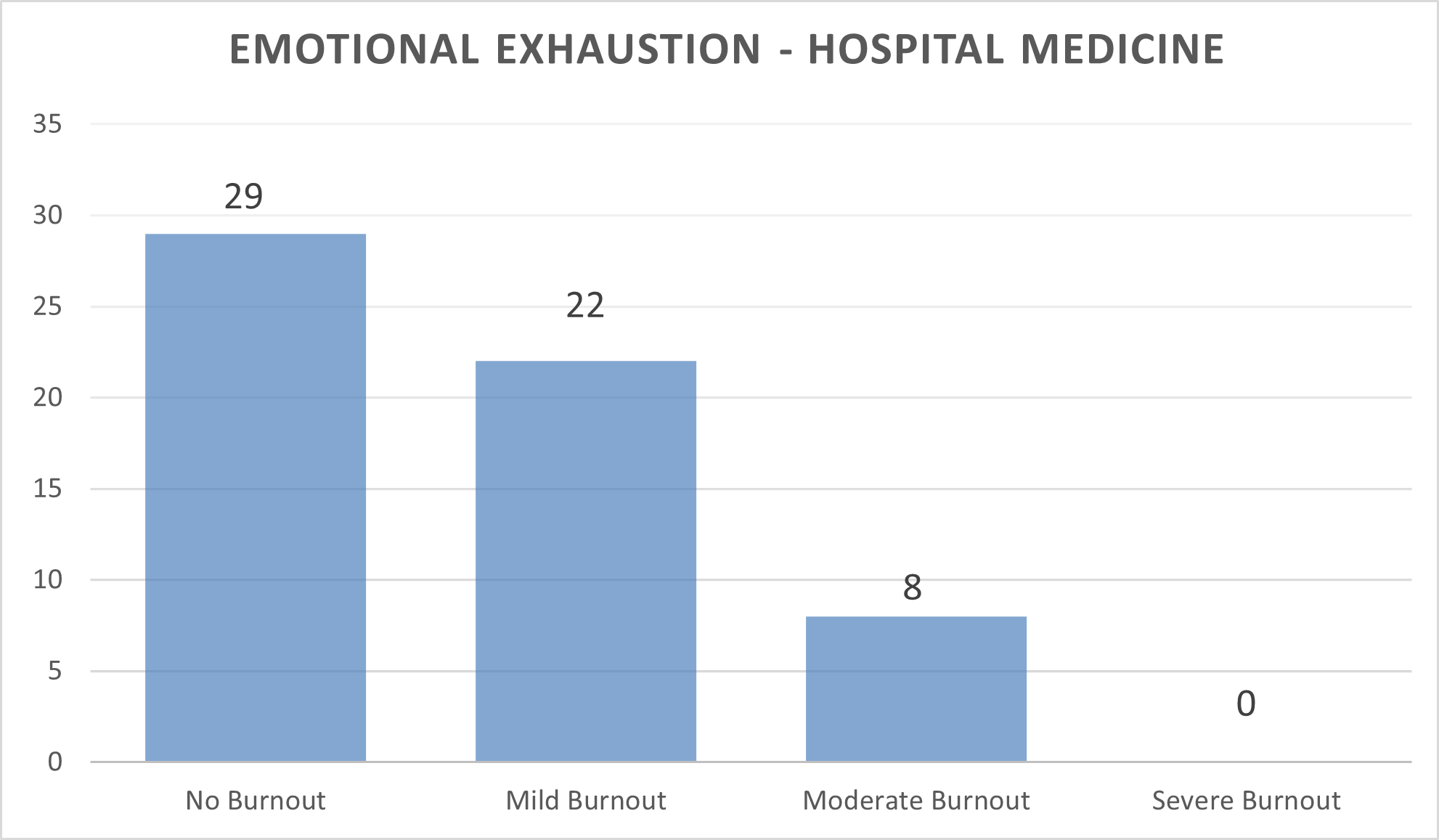

Results: We received 61 responses, a 78.2% response rate. We were able to capture a broad range of hospital medicine providers, from early career to seasoned hospitalists. Eighty-six percent of respondents were day hospitalists, 14% nocturnists, 10% APPs. The survey included 59% women and 41% men. Overall, 30 respondents (49%) met or exceeded the threshold for burnout. Twenty-nine respondents had no burnout symptoms, 22 respondents had mild burnout symptoms, 8 had moderate burnout symptoms and 0 hospitalists had severe burnout symptoms [Figure 1]. There was no statistically significant difference in emotional exhaustion scores for nocturnists compared with day hospitalists or for hospitalists with dependents. Additionally, while there was not a statistically significant difference in burnout when medical errors were analyzed, we did find a notable trend: hospitalists who indicated they had made a medical error in the last year had higher mean burnout scores compared with those who did not self-report a medical error. We also hypothesized that more time providing direct clinical care results in more burnout, where working less than 100% providing direct clinical care was protective. We thus compared hospitalist burnout scores with clinical time. These results were also not statistically significant, but surprisingly, we found that hospitalists who worked less than 100% providing direct clinical care (n=31) had higher emotional exhaustion scores than those with 100% clinical time (n= 24).

Conclusions: These results suggest that emotional exhaustion symptoms were common (49%) among hospitalists of a single large academic hospital as of March/April 2022. However, the severity of symptomatology was relatively low (36% mild EE, 13% moderate EE). We hope to enlarge the sample size by incorporating hospitalist groups at other regional institutions which may allow us to draw more conclusions about protective factors and the relationship of emotional exhaustion and medical errors. In the meantime, we are incorporating regular Leadership WalkRounds and Listening Sessions, contemporaneously acting on items we uncover. A follow-up survey will be dispersed at the end of 2022.