Background: Updated guidelines recommend testing for inherited or acquired thrombophilias only in rare situations in the acute inpatient care setting, as it has little impact on acute management of thromboembolic events, and in some situations, can be falsely positive leading to inappropriate care. Current data in our academic medical center indicate testing for thrombophilia occurs commonly in acute VTE and new stroke and represents an unnecessary cost and use of resources. A better understanding of the frequency and patterns of thrombophilia testing represent a significant quality improvement opportunity for hospitals to ensure that testing adheres to current guidelines.

Methods: Data was extracted from the electronic database warehouse (EDW) of a large tertiary academic medical center for nine laboratory tests that have been presently or historically associated with hypercoagulability for a one-year period (01/01/2016 – 12/31/2016). Location of testing was identified by hospital floor and also by the ordering service. Duplication of testing was also determined from prior encounters. Further, we assessed frequency of testing performed while on anticoagulation or in the setting of acute thrombosis, which may make test results unreliable. Total costs were quantified based on the cost of each test and the number of tests ordered.

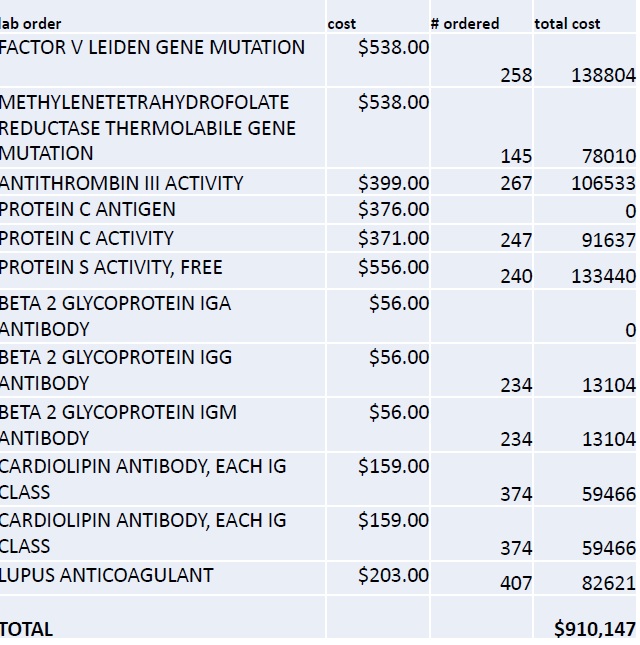

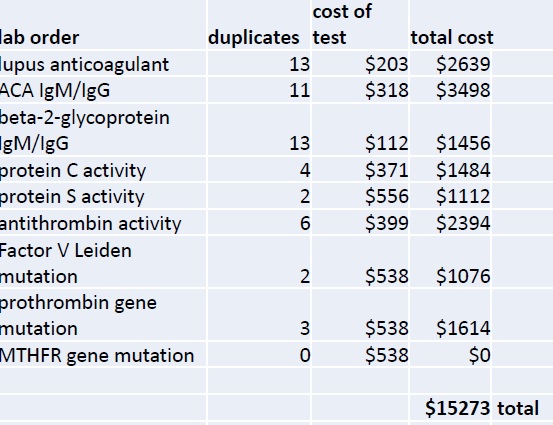

Results: In a one year period, 2421 thrombophilia labs were sent on 534 inpatients. Eight tests (lupus anticoagulant, ß2 glycoprotein antibody, cardiolipin antibody, protein C activity, protein S activity, antithrombin activity, Factor V Leiden gene mutation, and prothrombin gene mutation) were each ordered >230 times. Lupus anticoagulant and anti-cardiolipin antibody represented 18% of all tests. Testing based on services indicated the following: neurology 1206 tests (43%), medicine and its subspecialties 1107 tests (40%), surgery 338 tests (12%) and OB/GYN 134 tests (5%). 6% of testing was for the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene mutation, which current guidelines recommend should never be checked as part of a hypercoagulable workup up in any patient group. 54 lab orders represented duplicate testing in the same patient. Erroneous tests (similarly sounding tests but not hypercoagulable tests) were ordered in 96 instances. 132 tests were ordered while patients were on anticoagulation and could represent false positives. The total cost of all 2421 tests ordered during the study period represented $910K in hospital costs (Figure 1). Duplicate (Figure 2), erroneous and misleading testing in sum represented $118K in costs and accounted for 13% of all costs aside from an analysis of non-guideline based testing.

Conclusions: Testing for inherited thrombophilia is common in acute hospitalized patients at an academic medical center despite data that indicate that testing may not be necessary. Further analysis should be undertaken to determine the percentage of testing which represents non-guideline based testing with chart review and abstraction. Finally, 13% of all costs for thrombophilia testing are clearly wasteful and represent an immediate opportunity for cost savings.