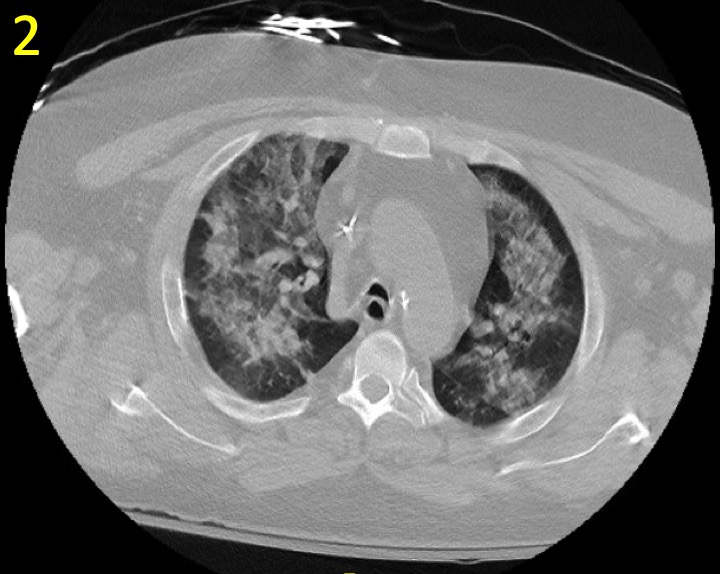

Case Presentation: A 49 year-old man with history of renal transplant due to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis on mycophenolate and prednisone presented with chest tightness, shortness of breath, and productive cough with white sputum for several weeks. He was admitted one month prior with similar complaints and diagnosed with multi-lobar pneumonia. On admission, vital signs were normal and oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. Physical exam was significant for bibasilar crackles. Laboratory studies showed white blood cell 4,000 cells/m3, hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL, and platelet 114,000 /μL. The remaining labs were significant for anion gap 17, serum CO2 19 mEq/L, BUN 42 mg/dL, creatinine 2.7 mg/dL, calcium 9.1 mg/dL, phosphorus 3.8 mg/dL, albumin of 2.9 g/dL, LDH 193 U/L, BNP of 343 pg/mL, troponin <0.3 ng/dL, IgG levels 350 mg/dL, IgA of 105 mg/dL, and IgE 0.3 UI/mL. Liver function and coagulation profiles were within normal limits, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, and rheumatoid factors were negative. Nasal swab culture was positive for coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. Chest radiograph (CXR) demonstrated right-lung-base opacification. Chest Computed Tomography (CT) displayed scattered focal densities and ground glass opacities in a bronchovascular distribution. Blood cultures were negative, serum polymerase-chain-reaction tests for herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) were negative, and respiratory pathogen panel was positive for Rhinovirus/Enterovirus. Bilateral pneumonia was diagnosed, and the patient was started empirically on meropenem and vancomycin. He developed worsening respiratory failure with wheezing, and new onset teaspoonful of hemoptysis. Sputum culture was positive for Aspergillus flavus; voriconazole and methylprednisolone were added for presumed Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis. The following day, he rapidly progressed to acute hypoxic respiratory failure and was transferred to ICU requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Repeat CXR showed worsening diffuse bilateral consolidations (Figure 1). CT Chest showed progression of focal consolidations (Figure 2). Bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) showed copious frothy blood tinged sputum and areas of friable mucosa without evidence of incremental sanguineous aliquots of BAL aspirates. BAL was positive for HSV-1, and acyclovir was initiated. His condition improved clinically and radiographically, and extubated within 48 hours.

Discussion: Differential diagnoses of pneumonia can be broad including bacterial, fungal, viral and non-infectious etiologies. Rare causes such as HSV in the immunocompromised population have a high mortality if left untreated. Superimposed infections, which occur more frequent in this population, create diagnostic challenges to the less common causes of pneumonia that may lead to delayed detection and appropriate treatment. Primary care physicians should exercise a high index of suspicion for superimposed infections in such patients and a BAL may be warranted early in the course to tailor treatment.

Conclusions: Diagnosing pneumonia may be difficult by cultures, imaging, or PCR testing alone — especially when complicated by superimposed infections –particularly in immunocompromised hosts. A high index of suspicion in recognizing less common causes of pneumonia through bronchoalveolar lavage in immunosuppressed patients is important to facilitate early detection and treatment to reduce mortality.