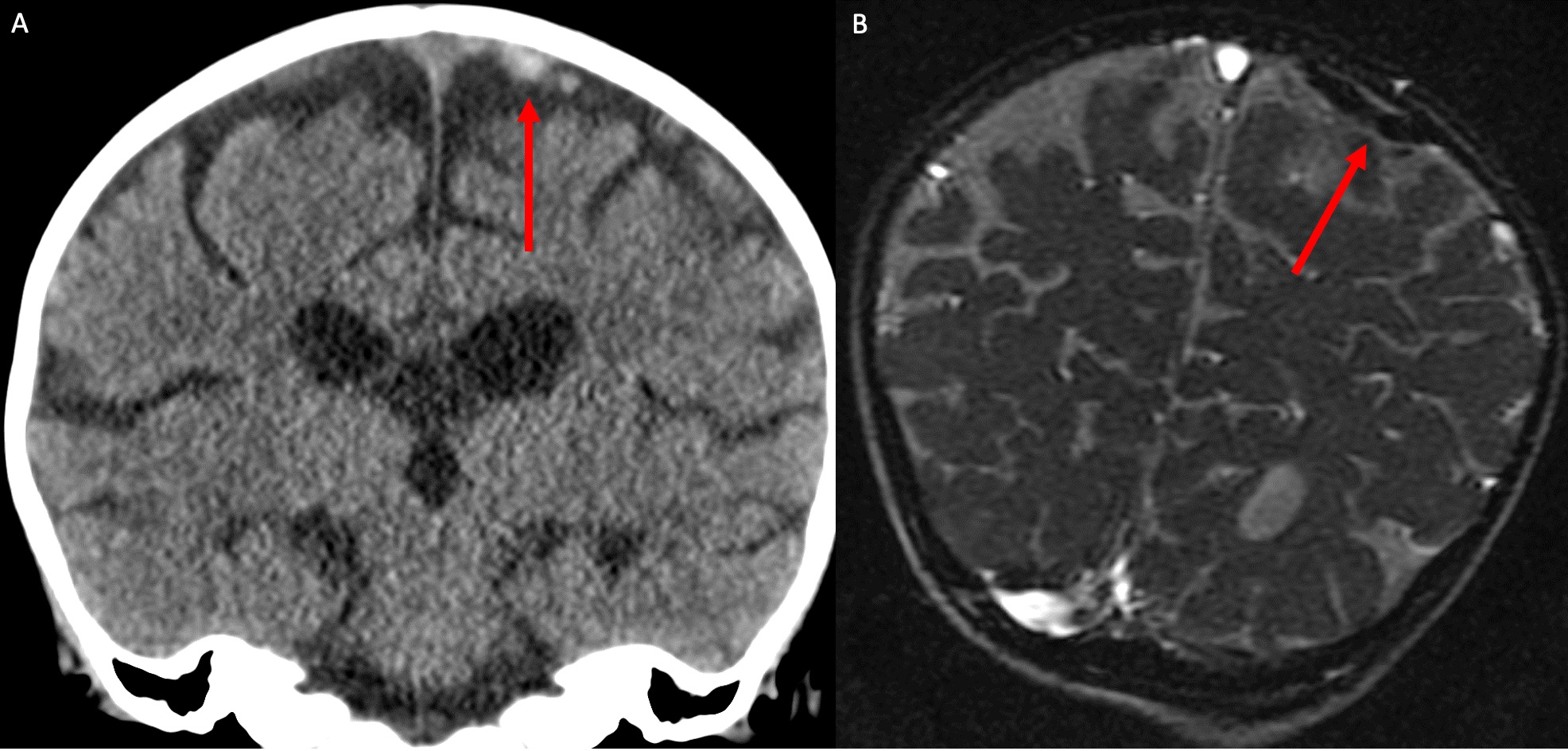

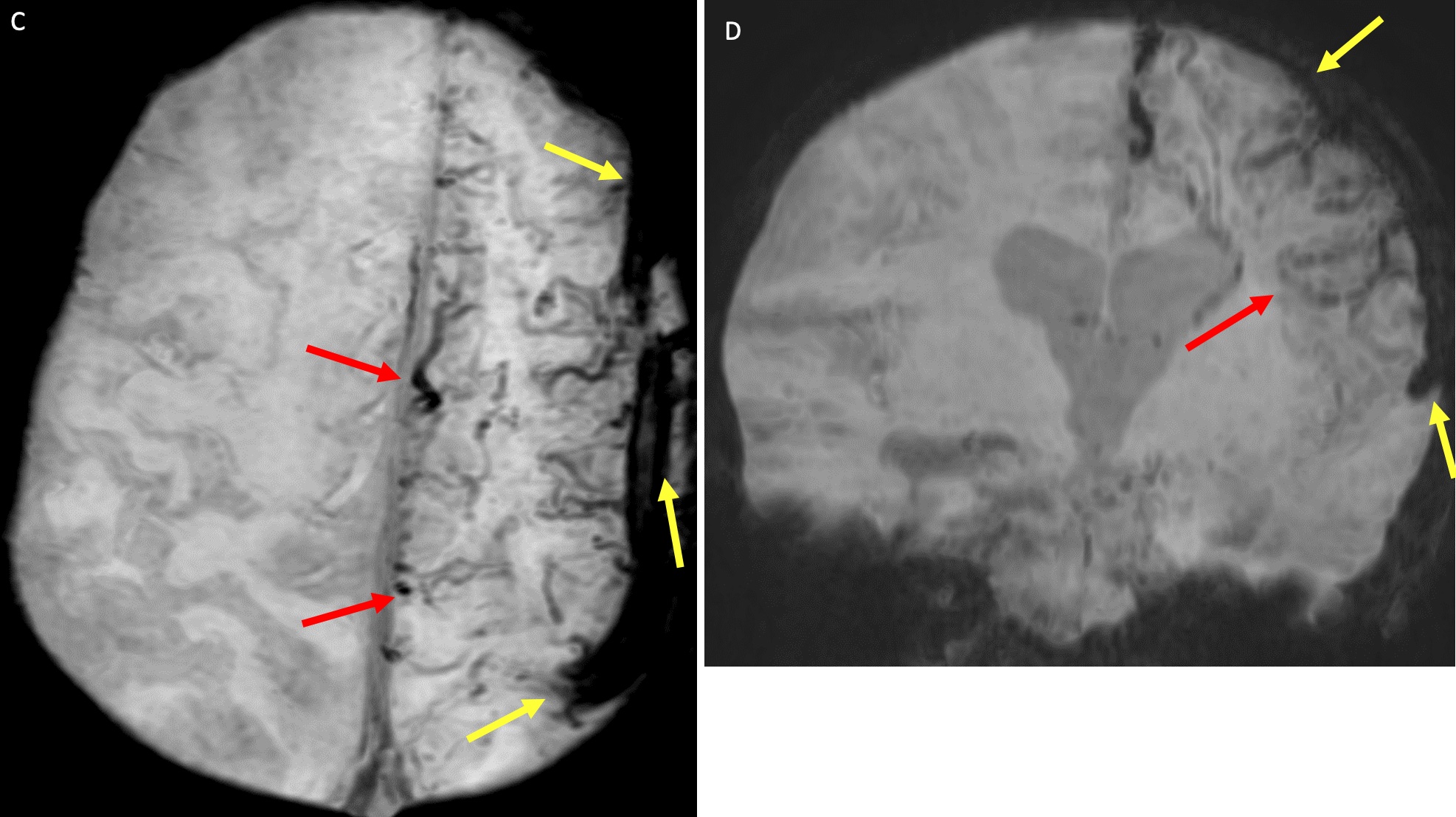

Case Presentation: A 21-month-old girl was brought to the emergency department for acute, severe right arm and leg weakness. She was unable to stand, appearing pale and fatigued. Labs were notable for hemoglobin (Hgb) of 3.5 g/dL, leukocyte of 19.7×103/µL, platelet of 340×103/µL, absolute reticulocyte of 6.4×103/µL, and MCV of 49 fL. Microcytic anemia and a history of drinking >24 oz whole milk daily prompted Hgb electrophoresis and iron studies. There was no evidence of thalassemia, but severe iron (Fe) deficiency anemia was diagnosed with an Fe level of 23 µg/dL, Fe binding capacity of 446 µg/dL, and Fe saturation of 5%. She required multiple pRBC transfusions and was started on ferrous sulfate.Brain MRI brain with and without contrast, and MRA/MRV head/neck revealed cortical venous abnormalities of the superior sagittal sinus, left transverse sinus, and left sigmoid sinus (figure 1). Impaired drainage and perfusion of the left cerebral hemisphere was also noted, along with increased deoxyhemoglobin (figure 2a, 2b). The impression was of chronic cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) with subsequent collateral vessel formation, diffuse punctate ischemia, and increased intracranial pressure. APS and lupus with beta 2-glycoprotein I IgG and cardiolipin IgG tests were negative.The patient was started on enoxaparin. Neurologic exam did not reveal cranial nerve or reflex defects. Labs performed on day 5 of hospitalization showed a Hgb of 8.2 g/dL, and MCV of 68 fL. With improvement in Hgb and a few sessions of physical therapy, her mobility returned to baseline. She was discharged on enoxaparin, iron supplementation, follow-up with hematology and neurology, with repeat MRI/MRA/MRV in 3 months.The patient was readmitted 6 days after discharge for right arm stiffness. An EEG was performed revealing focal left frontotemporal and frontocentral epileptiform discharges. She was started on Levetiracetam for seizure prevention. No more seizure episodes were noted. She was discharged home.

Discussion: Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) in children is often multifactorial in origin, some studies have noted the relation between iron deficiency anemia (1–9), though few cases have been reported in children under 2 years of age. Despite this presumed correlation, there has yet to be a definitive mechanism confirmed. Numerous studies have postulated including anemia induced thrombocytosis, hypercoagulability, and increased blood viscosity (2, 10-12). However, in this case our patient lacked signs of thrombocytosis, hyper-coaguable state, or altered blood viscosity. The degree to which this contributes to CVT has yet to be investigated. Regardless, treatment with Fe supplementation and anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin has been shown to result in a favorable prognosis (3).

Conclusions: CVT refers to obstruction of the cerebral veins or the dural sinuses by a thrombus. This often leads to significant increases in intracranial pressure, and in the acute setting can result in stroke, hemorrhage, or seizures. Several case reports of Fe deficiency anemia and CVT with seizures in adults and children have been documented (1–5). In children, the incidence of CVT has been increasing by 3.8% annually, with the incidence in infants occurring at a rate five times higher than teenagers, and nine times higher than children aged 1-4 years (7). Thus, it is important to recognize the signs of CVT in young children to avoid misdiagnosis and decrease morbidity and mortality (7,8).