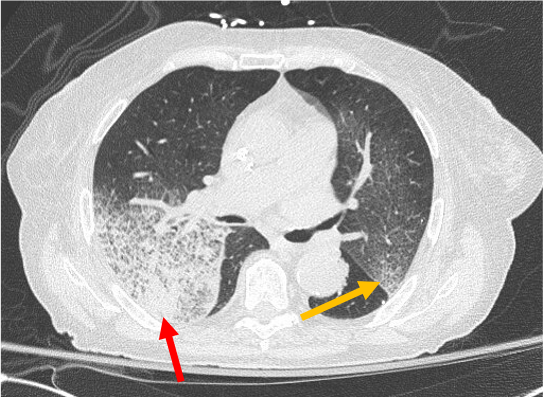

Case Presentation: An 82-year-old female with diastolic heart failure presented with one-month worsening dyspnea on exertion and a week of scant hemoptysis and fatigue. She denied tuberculosis risk factors, night sweats, fevers, or skin, joint, or urinary changes. She was fully vaccinated against COVID-19. Her medications included aspirin and hydralazine. Her past medical, surgical, and social histories were otherwise non-contributory. She was afebrile, hypertensive (180/68 mmHg), and hypoxic (85% on room air). She had bilateral expiratory wheezes on exam. Labs showed anemia (hemoglobin 9.8 g/dL), an elevated creatinine (1.3 mg/dL), proteinuria (30 mg/dL), and hematuria (71 red blood cells). Transthoracic echocardiogram showed mildly increased left ventricular wall thickness and normal function. Chest computed tomography showed no pulmonary embolism and asymmetric bilateral upper lobe ground glass attenuation superimposed on interlobular septal thickening and intralobular lines.Further testing showed positive anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti-nuclear antibody (ANA; >=1:640), and myeloperoxidase (MPO; 65.5 U/mL); negative antibodies to double-stranded DNA, Sm, RNP, Ro/SSA, La/SSB, Jo1, Scl70, glomerular basement membrane, and proteinase 3; negative infectious work-up; and normal complement 3 and 4. Renal biopsy revealed pauci-immune and necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis (+p-ANCA) in 5 of 26 glomeruli. She was diagnosed with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) secondary to hydralazine-induced ANCA associated vasculitis (AAV). She experienced brief respiratory improvement after discontinuation of hydralazine and initiation of methylprednisolone. Bronchoscopy was not performed, per patient wishes. Despite plasma-exchange and cyclophosphamide, her condition worsened, and she expired on comfort care.

Discussion: Hydralazine is an antihypertensive and afterload reducing medication with known potential for autoimmune reactions. Of these, AAV is a rare sequela mediated by anti-MPO (p-ANCA) and most commonly affects the kidneys. In very rare circumstances, patients with AAV can develop pulmonary-renal syndrome (PRS), resulting in both glomerulonephritis and DAH with an associated high risk of mortality. The pathophysiology is unclear, but it is hypothesized that hydralazine accumulates and binds to MPO in the cytoplasm of neutrophils, leading to release of cytotoxic products. Antigen presenting cells then produce ANCA and ANA when exposed to these normally sequestered antigens. Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion in patients with acute kidney injury of unclear etiology, especially those taking typical culprit medications. Early immune work-up and kidney biopsy should be considered. Treatment consists of discontinuing the culprit drug and immunosuppression with corticosteroids and biologics (methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil in non-life threatening AAV; cyclophosphamide or rituximab in life-threatening AAV). Plasmapheresis may be employed in severe cases (e.g., life or organ-threatening, creatinine greater than 5.7 mg/dL, severe DAH).

Conclusions: General internists should have a high level of suspicion for hydralazine-induced AAV causing DAH in the setting of hydralazine use, new anemia, hemoptysis, and hypoxemia. Given the high associated mortality in cases of PRS, prompt recognition of the vasculitis, cessation of hydralazine, immunosuppression, and early plasma-exchange are essential to an improved prognosis.