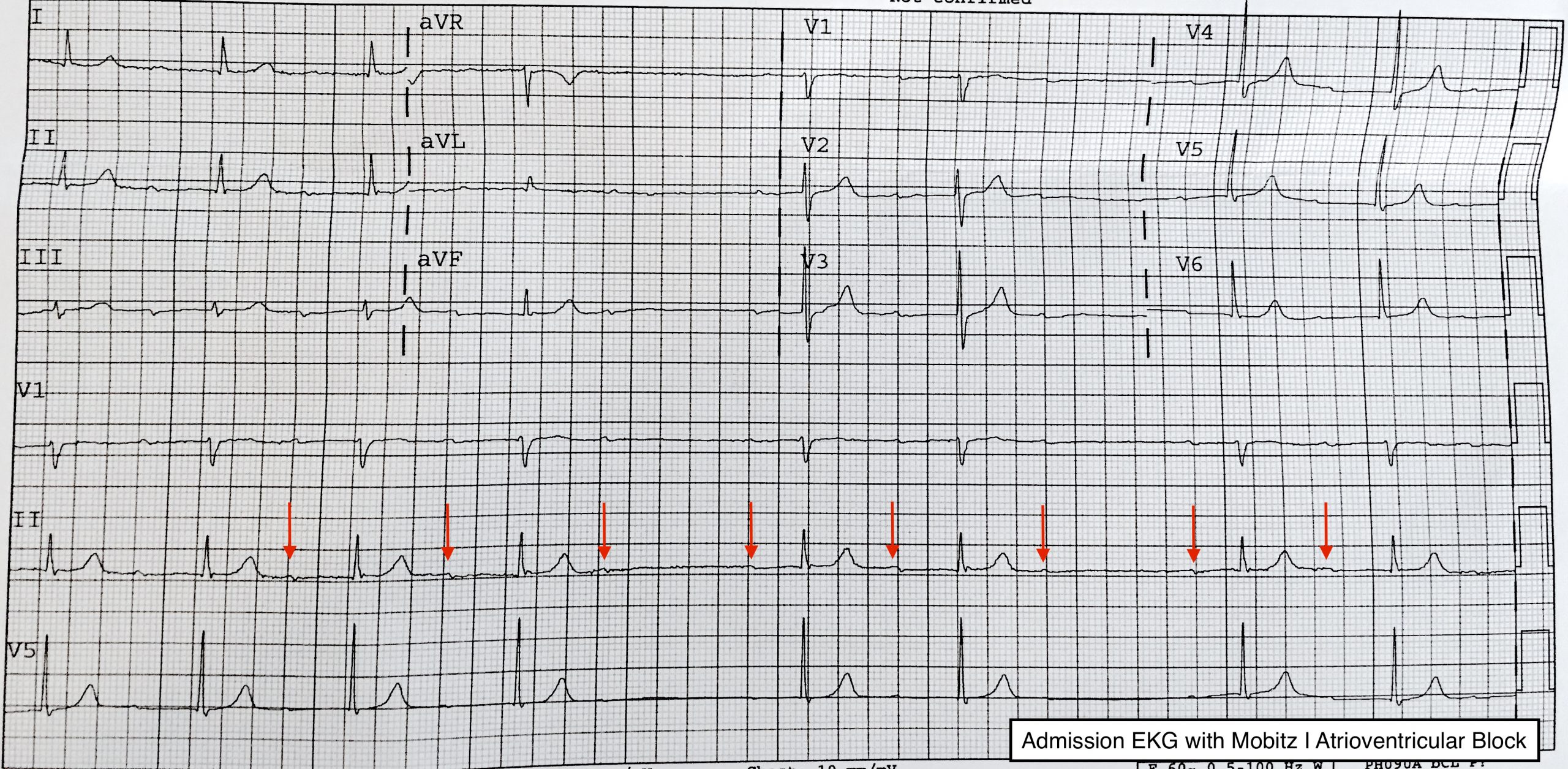

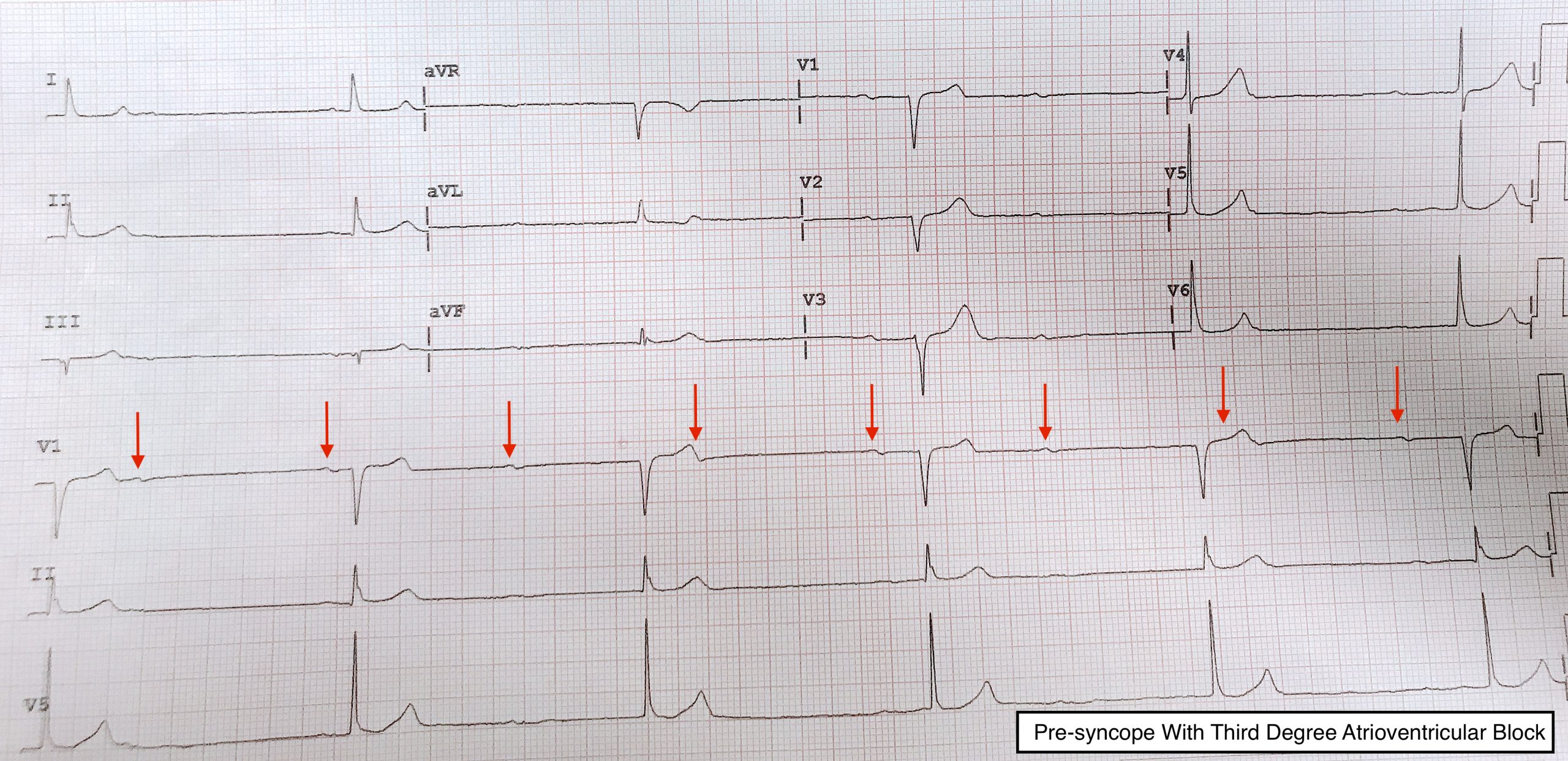

Case Presentation: A 77 year old man with a history of first degree heart block, hypertension, type II diabetes, and alpha thalassemia trait presented with one day of lightheadedness and palpitations. Several days of fatigue, myalgias, sore throat, rhinorrhea, and headache preceded his symptoms. His exam was notable for bradycardia but was otherwise normal. Labs revealed a stable anemia with normal potassium, troponin, and TSH. EKG showed sinus bradycardia with Mobitz type I atrioventricular block (AVB) (Fig. 1). Echocardiogram was unremarkable. Telemetry demonstrated first degree with intermittent second degree Mobitz I AVB. On hospital day two, several episodes of second degree Mobitz type II AVB were seen among the baseline rhythm. These episodes were asymptomatic. On hospital day 4, the patient had an episode of presyncope. He was bradycardic with third degree AVB on EKG (Fig. 2). A permanent cardiac pacemaker was placed, and he was discharged.

Discussion: The management of first degree, second degree Mobitz II, and third degree AVB is well-established. First degree AVB is considered largely benign; management includes periodic monitoring (1,2). Second degree Mobitz II AVB is high risk for progression to third degree block, in which the heart rate is determined by either junctional or ventricular escape rhythms. Third degree AVB is potentially unstable, and carries a high risk of causing cardiogenic shock. An implantable pacemaker is indicated in almost all cases of Mobitz II and third degree AVB (1,2), as this reduces the risk of cardiogenic shock and improves mortality. Mobitz I AVB has classically been considered benign and unlikely to progress to third degree AVB, though this is controversial. The American College of Cardiology (ACC) guidelines have previously recommended against pacing patients with Mobitz I AVB (3). However, the European Society of Cardiology believes that there is mixed evidence that generally favors pacing Mobitz I AVB (1). Should Mobitz I patients be paced? Multiple studies demonstrate not only a high mortality risk in unpaced Mobitz I AVB, but also the mortality benefits of pacing. In one prospective study, Mobitz I AVB had a similar prognosis to Mobitz II AVB (4). In another, unpaced Mobitz I AVB patients had a significantly lower survival at 5 years compared to paced Mobitz I patients, who had a survival close to that of the average population (42% vs 78%) (4). Mortality benefit to pacing held true in Mobitz I AVB patients with no coronary disease, heart failure, or left ventricular dysfunction (43% paced vs. 65% unpaced) (5). Even in Mobitz I AVB patients without symptoms of bradycardia, pacing improved 5 year survival (87% vs 54%) (6). There is compelling evidence for a lower threshold to pace Mobitz I AVB patients. The 2018 ACC guidelines now allow pacing Mobitz I AVB, but only when symptoms “are clearly attributable to the atrioventricular block” (2). In clinical practice, a clear association of symptoms with arrhythmia is extremely difficult to accomplish. Had the patient in this case only demonstrated Mobitz I AVB, he would have been discharged without a pacemaker. This case highlights the controversial juncture in the management of Mobitz type I AVB.

Conclusions: Atrioventricular block is frequently seen in the inpatient setting, and is often dynamic. The management of Mobitz I AVB is controversial. Per guidelines, pacing is predicated on strict temporal correlation between symptoms and arrhythmia, though several studies suggest mortality benefit with a less stringent approach to pacing.