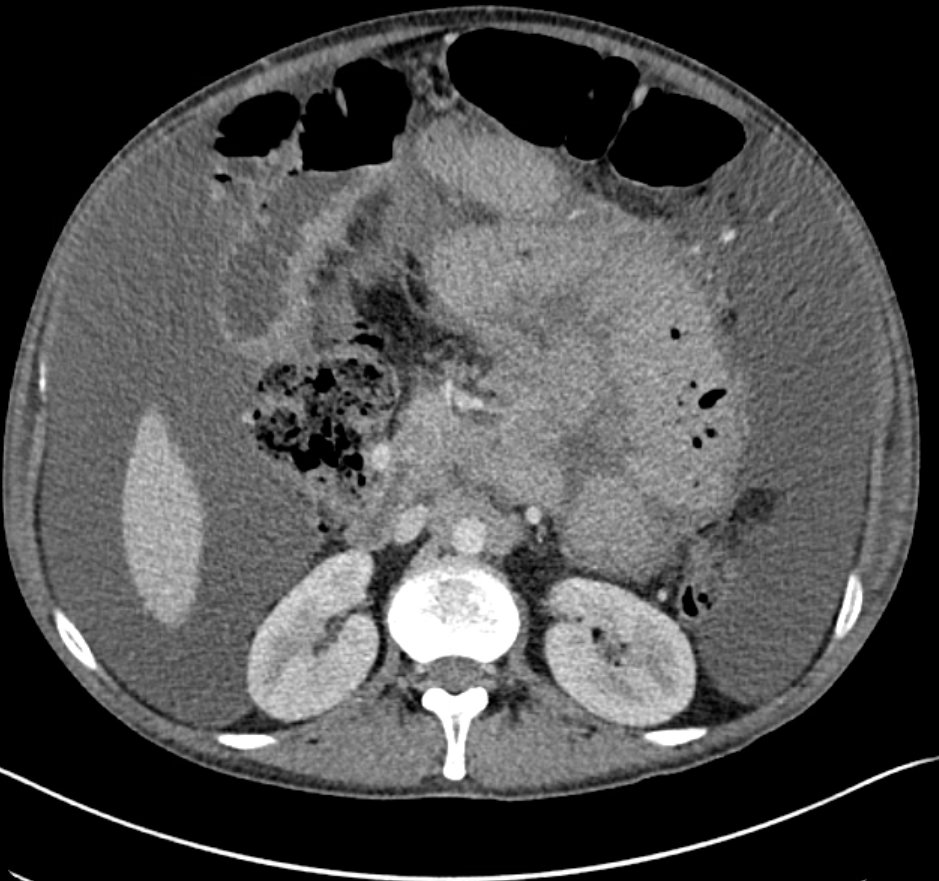

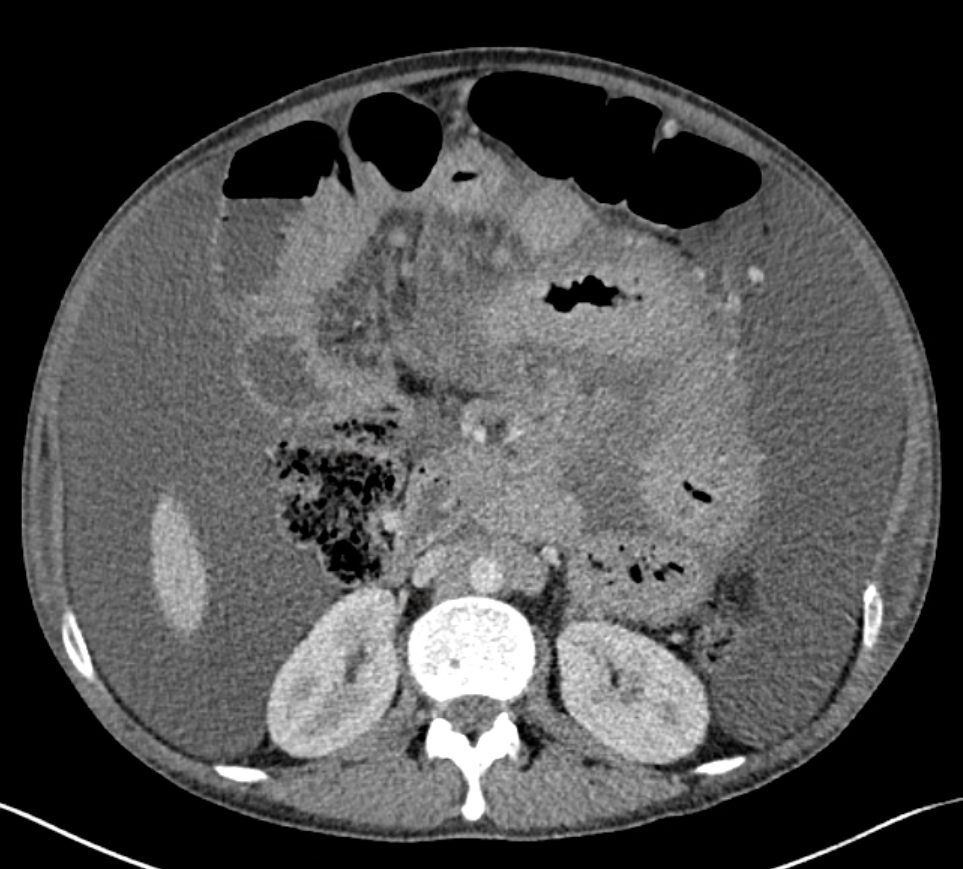

Case Presentation: A 29-year-old male with a history of HIV/AIDs on antiretroviral therapy (ART), prior cryptococcal meningitis, and mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) colitis presented to the ED with a three-week history of worsening abdominal pain and distension. His MAC colitis was diagnosed earlier that year and treated with clarithromycin and ethambutol. However, the ethambutol was discontinued due to concern for optic neuritis, so he was switched to macrolide monotherapy for three months. He had normal vital signs and physical exam showed abdominal distension with a positive fluid shift and diffuse tenderness to palpation without guarding or rebound tenderness. Labs were notable for mild elevation of alkaline phosphatase (192 U/L), anemia (Hgb 10.6 g/dl) and thrombocytosis (607 10³/µL). CT abdomen demonstrated abnormal soft tissue/nodularity along the root of the small bowel mesentery and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy with ascites and mesenteric edema. He underwent paracentesis which revealed chylous ascites and cultures were positive for MAC. The patient endorsed mild relief of his abdominal symptoms after the paracentesis, but his abdomen became noticeably distended in the days following. After negative ophthalmologic workup, ethambutol was resumed along with azithromycin and rifabutin. He required repeat outpatient paracentesis due to fluid re-accumulation.

Discussion: MAC infections in persons with HIV on ART is rare, however, the risk remains for patients with CD4 count < 50 cells/microL, high viral load, or previous opportunistic infection (1). Patients with disseminated MAC infection often present with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, night sweats, abdominal pain and diarrhea, and lab abnormalities of anemia, elevated alkaline phosphatase, and lactate dehydrogenase (2). This patient reported adherence to ART with an undetectable viral load, but his CD4 count was low (between 3-23 in the months prior), and he had a history of cryptococcus meningitis infection. Together with his symptoms and lab findings, his presentation was concerning for sequelae of MAC infection vs an alternative etiology for ascites. Chylous ascites is an uncommon sequelae of MAC colitis in HIV/AIDs patients (3,4,5). Its differential diagnosis includes cirrhosis, malignancy, and lymphatic obstruction (6). The patient had imaging demonstrating lymphadenopathy along the small bowel mesentery. Given his clinical picture, MAC colitis leading to lymphatic obstruction appeared to be the most reasonable explanation for his chylous ascites. This case highlights the challenge in managing MAC infections. The patient had previously been treated with clarithromycin and ethambutol; a dual therapy considered the mainstay of treatment (7). However, given concerns for vision changes, ethambutol was discontinued leading to incomplete treatment for more than 3 months, which likely contributed to his worsening symptoms and overall presentation.

Conclusions: Hospitalists should consider MAC colitis with chylous ascites in patients with HIV/AIDs on ART with low CD4 count. Patients may present with nonspecific symptoms and lab abnormalities of anemia, elevated alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase. CT is useful to evaluate for lymphatic obstruction secondary to MAC infection. Patients with MAC infections should be treated promptly with a macrolide plus ethambutol. Should ethambutol be discontinued for ophthalmologic concerns, prompt replacement with an appropriate alternative is indicated.