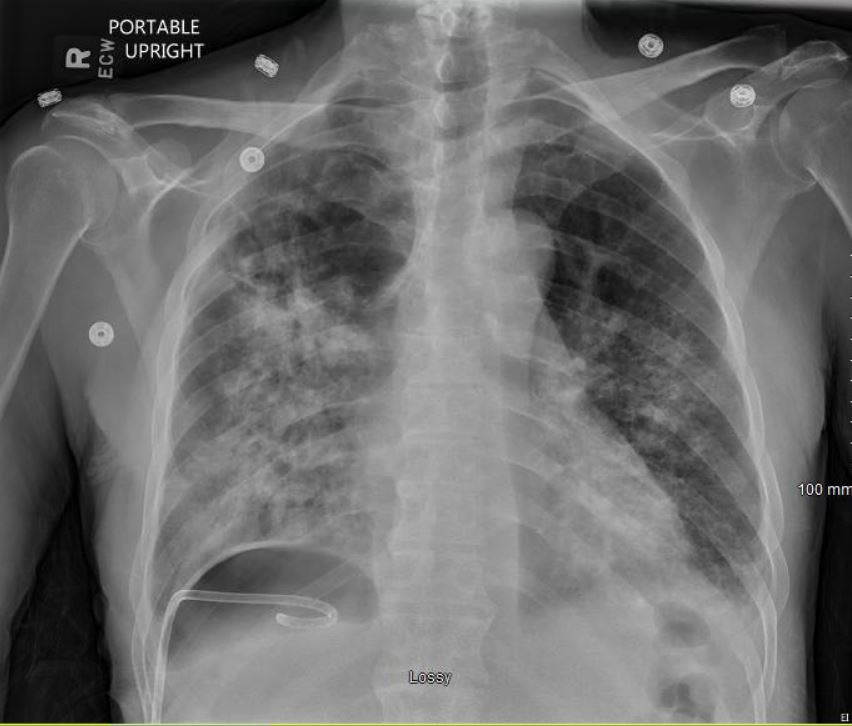

Case Presentation: A 68-year-old male presented with cough, SOB, decreased appetite, 30lb weight loss over two months, and generalized weakness. He reported a remote history of alcohol abuse and tobacco use. He was admitted two months prior for cough and SOB to another hospital with findings of a right upper lobe cavitary lung lesion. He was discharged after workup was negative for malignancy. On presentation, he was afebrile and ill-appearing with labored breathing and hypoxemia requiring 5L O2 via NC. Breath sounds were diminished in the right hemithorax and absent in the right lower lung field. WBC count on admission was 9500. Rapid COVID-19 PCR negative. CT chest showed a large RLL pyopneumothorax, RLL BPF, and extensive consolidation of the right lung. He was initially treated with oral azithromycin and IV ceftriaxone. A pigtail pulmonary drain (PD) was placed with aspiration of frank pus. Extensive infectious workup was negative, however due to purulent drainage, azithromycin and ceftriaxone were converted to IV ampicillin-sulbactam. The PD continued to drain purulent material for the next 14 days with substantial improvement in cough, SOB, and appetite. The BPF failed to close spontaneously, however, as evidenced by multiple trials of placing the PD to water seal resulting in re-development of the pneumothorax. The patient was adamant about avoiding surgical intervention, thus a betadine pleurodesis was performed on HD 15. CXR on HD 16 with PD to water seal showed no pneumothorax, indicating resolution of the BPF. The PD was removed on HD 17 with repeat CXR showing only small pneumothorax. He was discharged HD 17 without oxygen needs to complete a four-week course of antibiotic therapy.

Discussion: BPFs are common in the inpatient setting and can be caused by complicated pyopneumothorax (as in this case), cavitary lung infection, thoracic surgery, and lung biopsy. The gold standard of treatment for BPF is surgical repair if spontaneous closure is not achieved with a PD within four days. For patients who wish to have less invasive procedures or for whom surgery is contraindicated, there is not a well-established consensus on the best treatment choice. More conservative choices include chemical pleurodesis, autologous blood patch pleurodesis, fibrin sealants, metal coils, and one-way endobronchial valve placements. In chemical pleurodesis, the chemical (eg. betadine, talc, tetracyclines) is delivered via the PD causing inflammation and fibrosis in the pleural space. This allows adherence of the lung to the chest wall thus closing the fistula and preventing recurrent pneumothorax. Common side effects include fever and chest pain which typically resolve quickly; less commonly an empyema or acute lung injury can occur.

Conclusions: This case demonstrates the importance and effectiveness of utilizing less invasive, more conservative options in treating BPF that fail to close spontaneously. Chemical pleurodesis is a minimally invasive procedure that can be done at bedside and should be considered before proceeding with more invasive measures which can entail higher risks, longer recovery times, higher costs, and greater anxiety for the patient.